Slaughterhouse Case

The US Supreme Court ruling in the Slaughterhouse Case was the first interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment by the high court and resulted in diminished civil rights protection for citizens.

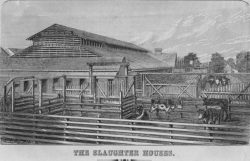

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Slaughter Houses. Orr, John William (Artist)

Louisiana’s Slaughterhouse Case began with an effort to centralize and clean up the wholesale butchering trade during Reconstruction in New Orleans. In that pre-refrigeration era, the process was viewed as a public nuisance, if not an outright health hazard. When local butchers were forced to take their animals to the city’s only approved slaughterhouse and pay high fees to have their animals slaughtered there, they filed suit, protesting what they characterized as an illegal monopoly and the unconstitutional loss of their property rights. The legal challenge ultimately was decided by the US Supreme Court, with unexpected consequences that diminished some of the civil rights protections that had been granted by the Fourteenth Amendment in the wake of Emancipation.

Legal Dispute

In 1869 the Louisiana legislature passed a law that allowed New Orleans to create a corporation to centralize all slaughterhouse operations in the city, thereby creating Crescent City Live-Stock Landing and Slaughter-House Company to do all cattle slaughtering in the city. The reason for the statute was health. Until the time of the ruling, cattle dealers landed hundreds of cows, pigs, and sheep every day at Slaughterhouse Point, a few miles from New Orleans, and drove the terrified animals through the streets to various butchers who skinned, gutted, and hung the animals’ carcasses on hooks to dangle—unrefrigerated—for hours and sometimes for days. The butchers threw the gory waste into the streets or the Mississippi River, fouling the air and water in a city already plagued by filth and disease. Worse, New Orleans had no public sewer system. A group of local butchers formed the Butchers’ Benevolent Association, hired former US Supreme Court Justice John A. Campbell as their attorney, and sued in state court, arguing that the law, by depriving them of their livelihoods, violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s ban on state laws that “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” The state court ruled against the butchers and upheld the state’s slaughterhouse statute. The butchers appealed this decision to the US Supreme Court, which did not rule until 1873.

Decision

The vote was five to four against applying the Fourteenth Amendment to the Slaughterhouse Case because, the majority insisted, Congress had intended primarily to give citizenship rights to former slaves. Had the five majority justices stopped there, the decision would not have been so far-reaching, but they added that the amendment protected only such federal rights as access to ports and the right to run for office. Basically, then, the five justices said that the Fourteenth Amendment had not fundamentally altered traditional federalism in the sense that most citizens’ rights remained under state control, and the amendment had nothing to do with states’ rights. The privileges-and-immunities clause did not protect rights flowing from state citizenship, only those arising out of national citizenship, the court held.

Dissenters

Among the four dissenters, Justice Stephen Field posited that the Fourteenth Amendment did indeed shield property rights and the right to labor from interference by the individual states. If the amendment’s meaning was to do otherwise, Field wrote, “It was a vain and idle amendment, which accomplished nothing, and most unnecessarily excited Congress and the people on its passage.” Another of the court’s minority of four, Justice Noah Swayne, angrily declared, “This court has no authority to interpolate a limitation that is neither express nor implied. Our duty is to execute the law, not to make it.”

The ruling provided an important affirmation of the states’ “police power” to protect public health and safety and otherwise to regulate business activities for the good of the community. However, it also curtailed the value of the Fourteenth Amendment’s privileges-and-immunities clause for protecting the fundamental rights of citizens, notably former slaves, from restrictions that state governments might choose to apply. With many state legislatures in the post-Reconstruction South controlled by former slaveholders, African Americans in most of those states were left in the disadvantageous position of having to rely on those state governments and their constitutions for the guarantee of their personal rights.