Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina’s landfall in Louisiana and the subsequent levee failures resulted in one of the worst disasters in United States history.

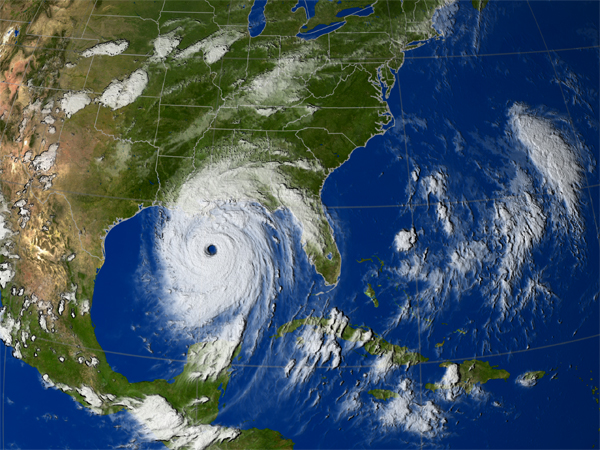

Courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio.

Hurricane Katrina IR clouds from GOES on August 29, 2005.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, the most destructive and costly natural disaster in US history, came ashore near the border between Mississippi and Louisiana. A year after the storm, the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals recorded 1,464 deceased victims of Katrina in the state. That number later rose to 1,577. The death and destruction from the hurricane and the subsequent flooding brought international media attention to Louisiana and prompted heated debate about the effectiveness of local, state, and federal officials in preparing for the storm and responding to its aftermath.

The Storm

In anticipation of the storm, officials in Plaquemines and St. Charles Parishes declared a mandatory evacuation on August 27, 2005. The same day, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin and Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco held a press conference to discuss the potential severity of the storm. Nagin declared a state of emergency in New Orleans but did not order a mandatory evacuation until August 28. Using a contraflow system, in which inbound road lanes were used for outgoing traffic, officials evacuated an estimated 1.2 million people, 92 percent of the affected population, before Katrina came ashore. Despite the evacuation order, approximately 100,000 people remained in the city as the hurricane came ashore, many because they lacked transportation. Hundreds of those left behind died in the subsequent flooding.

The eye of Hurricane Katrina made landfall near Buras in Plaquemines Parish at approximately 6:00 a.m. on August 29 as a Category 3 hurricane. (Weather forecasters classify hurricane strength on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the strongest.) At landfall, Katrina’s maximum winds were about 125 miles per hour (mph) to the east of its center. Shortly before landfall, Katrina was moving at 12 mph, a relatively slow speed for hurricanes. A slow-moving storm, however, can be more destructive than one that moves quickly. At 5:00 a.m., the US Army Corps of Engineers received a report that the 17th Street Canal had been breached. At 8:14 a.m., the Industrial Canal was breached, flooding the Lower Ninth Ward. By 4 p.m., the London Avenue Canal levees had breached as well, leaving approximately 80 percent of the city underwater.

Beyond New Orleans, Katrina caused severe destruction along the Gulf Coast, from Florida to Texas. In Louisiana, the storm destroyed nearly every building in lower Plaquemines Parish. In St. Bernard Parish, a massive storm surge sent water over the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet and the Industrial Canal, submerging 95 percent of the parish. In St. Tammany Parish, more than 40,000 homes were damaged—almost 20,000 by flooding. In addition, Katrina caused power outages in 1.1 million homes and other buildings in Louisiana and Mississippi. The storm also forced the temporary shutdown of eight Louisiana oil refineries, whose output accounted for 8 percent of US refining capacity.

The Immediate Impact

Before the storm made landfall, the New Orleans Superdome was opened as a shelter of last resort for those who had not evacuated. By August 31, about 26,000 people had filled the Superdome, which lacked the food, electrical power, and bathroom facilities to accommodate all of them. Stranded evacuees also occupied the Ernest J. Morial Convention Center. One estimate suggested that as many as 25,000 evacuees crowded the center, which also lacked provisions and accommodations for those who sheltered there. Some of these evacuees were transported to the Houston Astrodome, which was opened shortly after the storm to those seeking shelter. Efforts to evacuate the occupants of the Superdome and Convention Center to safety were not completed until September 3.

An estimated 4,000 evacuees were stranded on the Interstate 10 overpass in New Orleans. In addition, hundreds of hospital staff members and patients were stranded in New Orleans after Katrina, and all but one of the hospitals was without power. A lack of supplies complicated efforts to treat the patients. In the week following the storm, more than 3,000 patients were evacuated by air from a medical treatment operation established at the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, the largest such air evacuation in history. The hospitals were not fully evacuated, however, until September 2.

Katrina greatly disrupted communications within Louisiana, knocking down cell phone and radio towers and preventing officers with the New Orleans Police Department from talking with each other. Looting throughout New Orleans was widespread in the immediate aftermath of the storm. The arrival of 13,000 National Guard troops, along with President George W. Bush’s deployment of 7,000 active-duty troops to the Gulf Coast, helped restore order amid widespread complaints that the troops had not come quickly enough. On September 15, Bush stood in New Orleans’s Jackson Square and delivered a televised address to the nation. Speaking of a city that was, in his words, “nearly empty, still partly underwater, and waiting for life and hope to return,” the president pledged, “We will stay as long as it takes to help citizens rebuild their communities and their lives.” Many other dignitaries visited New Orleans in the weeks after Katrina, including King Abdullah of Jordan and Prince Charles of England and his wife, Camilla.

Hurricane Rita further complicated evacuation and recovery efforts when it made landfall along the Louisiana-Texas border on September 24. Like Katrina, Rita came ashore as a Category 3 storm. Five people died during the storm, and property damage along the coast of southwestern Louisiana and Texas was extensive. Despite the setback, on September 30, much of New Orleans was reopened, allowing evacuees to return to what was left of their homes.

In response to Katrina and Rita, the federal government allocated $71.5 billion to Louisiana for recovery and rebuilding efforts through various pieces of legislation. More than 1.1 million Americans volunteered to help in the wake of Katrina, providing assistance in recovery efforts across the Gulf Coast. Shortly after the storms, Governor Blanco authorized creation of the Louisiana Recovery Authority (LRA) to guide recovery and rebuilding from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The LRA estimated property damage from the two storms at between $75 billion and $100 billion. The US Government Accounting Office estimated that demolition and renovation of damaged property in the New Orleans area after Hurricane Katrina resulted in 100 million cubic yards of debris. Katrina also generated the largest single loss in the history of the US insurance history, with $41.1 billion in payments made on more than 1.7 million claims. Claims in Louisiana accounted for 63 percent of those losses.

Long-Term Impact

As the rebuilding process began, state, local, and federal officials traded blame for delays in the evacuation, which became a subject of prolonged controversy. Widespread criticism of the federal response to Katrina led to the resignation of Michael Brown as director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). His successor, R. David Paulison, promised to reform agency operations. Even after Brown’s departure, criticism of the Bush administration’s Katrina response continued, figuring into the 2008 presidential race. After facing heated criticism for her role in Katrina’s response and recovery efforts, Blanco announced on March 20, 2007, that she would not seek reelection.

Katrina also prompted an extensive public debate about the failure of New Orleans’s levees, which are overseen by local levee boards and the US Army Corps of Engineers. In 2006, Blanco signed a law to consolidate levee boards and streamline oversight. The same year, the US Army Corps of Engineers, which was responsible for levee design, issued a report acknowledging that design flaws in the levees caused most of the flooding associated with Hurricane Katrina.

The long-term effects of the storm on the state’s population remain to be seen. Katrina prompted the evacuation of 1.2 million Louisianans, many displaced for months or years. Thousands of evacuees ended up in other states, and some chose to resettle permanently. By 2009, New Orleans had regained about 75 percent of its pre-Katrina population. The storm also prompted renewed calls to restore Louisiana’s barrier islands to increase the state’s natural protection against future hurricanes. In 2009, President Barack Obama created a federal task force to oversee this restoration of the Louisiana and Mississippi coastlines. Katrina also devastated the state’s wetlands, already in peril before the storm, leading to increased efforts to protect these natural resources.