Troyville Earthworks

Located near Jonesville, the Troyville earthworks are a Baytown period Native American archaeological site that dates from 400 to 700 CE.

Wikimedia Commons

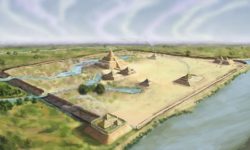

Artist Herb Roe's conception of the Troyville earthworks, a complex built and in use during the Baytown period from AD 400 to 700.

Located near Jonesville in Catahoula Parish, the Troyville earthworks are a Baytown period Native American archaeological site that dates from 400 to 700 CE. The site once included the tallest mound in Louisiana, at eighty-two feet in height; however, throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the unprotected historical complex was haphazardly destroyed. This devastation culminated in a road project in the 1930s, when earth was stripped from the main mound and used as infill for a bridge approach. Consideration has been given to replicating the largest mound for the benefit of tourism, but the destruction of Troyville is considered to be one of the most insensitive and irreplaceable losses in all of North American archaeology.

A Landmark throughout Time

The period between 400 and 700 CE in Europe is part of the Dark Ages. Foreign invaders ravaged the region, epidemics were rampant, economic and cultural conditions worsened, and the population declined substantially. In contrast, Native Americans in the Lower Mississippi Valley were experiencing positive cultural and economic change, and their population grew during this time. A long history of constructing monumental earthworks for religious and political purposes continued. Deep within a vast bottomland hardwood swamp, the Troyville mound complex rose in present-day Catahoula Parish. The principal structure was the second-tallest mound in eastern North America. When President Jefferson read of its discovery, he considered the find so important that he briefed Congress. Today, nothing of this archaeological treasure remains visible to the untrained eye. Its destruction began with the invasion of the descendants of those who survived Europe’s Dark Ages.

Louisiana archaeologists refer to the time between 400 and 700 CE as the Baytown period, and artifacts associated with the Troyville site have been radiocarbon dated to this period. The local culture associated with this time span is designated as the Troyville culture, named after the site; Troyville was an early name for present-day Jonesville. The Troyville site is in the Mississippi floodplain and lies on the west bank of the Black River at its confluence with the Little River. It consisted of at least nine mounds bounded by a D-shaped earthen embankment and the high banks of both rivers.

Early Accounts

By the late seventeenth century, early French explorers had noted the abandoned cluster of mounds at the junction of the two rivers (and just downstream from the mouth of a third—the Tensas). William Dunbar provided the first written description when he and George Hunter passed by on their exploration of the Ouachita River valley. The expedition, sponsored by Thomas Jefferson, landed at the site on October 23, 1804, and found a Frenchman by the name of Hebrard living in a cabin on the largest mound and operating a nearby ferry. Dunbar thought the site to be of such importance that he returned in January 1805 to make a detailed account for the president. Maj. Amos Stoddard, the first American commandant of Upper Louisiana after the Louisiana Purchase, described the site in 1812:

No less than five remarkable mounts are situated near the junction of the Washita, Acatahola, and Tenza, in an alluvial soil. They are enclosed by an embankment, or wall of earth, at this time ten feet high, and ten feet wide, which contains about two hundred acres of land. Four of these mounts are nearly of equal dimensions, about twenty feet high, one hundred feet broad, and three hundred feet long. The fifth seems to have been designed for a tower or turret; the base of it covers an acre of ground; it rises by two steps or stories; its circumference gradually diminishes as it is ascended and its summit is crowned by a flatted cone. By an accurate measurement, the height of this tower or turret has been found to be eighty feet.

Several other influential men wrote of the site in the nineteenth century. Mark Twain visited the area on a relief boat during the flood of 1882 and included his observations in Life on the Mississippi:

Troy, or a portion of it, is situated on and around three large Indian mounds, circular in shape, which rise above the present water about twelve feet. They are about 150 feet in diameter, and are about two hundred yards apart. The houses are all built between these mounds, and hence are all flooded to a depth of eighteen inches on their floors. These elevations, built by the aborigines, hundreds of years ago, are the only points of refuge for miles. When we arrived we found them crowded with stock, all of which was thin and hardly able to stand up.

Cyrus Thomas was one of the first scientists to excavate the site and describe the mounting damage in 1894. He said the large mound was “so gashed and mutilated, having been used during the [Civil] war as a place for [Confederate] rifle pits, that its original form can scarcely be made out.” A modern cemetery on top of the mound and erosion caused by overgrazing contributed to the destruction.

The Twentieth Century

The site’s archaeological value continued to be ignored throughout the first third of the twentieth century—until it was too late. The larger mounds served as places of refuge for humans and livestock during years of high water. People routinely hauled soil from the earthworks to elevate house sites and to fill depressions in the growing town of Jonesville. The death knell for the grand site sounded in Baton Rouge when Gov. Huey P. Long announced his ambitious statewide road and bridge building program in a two-pronged effort to upgrade the state’s infrastructure and bring employment relief to those suffering in the Great Depression. One of Long’s projects was the construction of a bridge across the Black River at Jonesville. Engineers designed the western approach to the bridge in an exact alignment with the large mound. As a source of fill for the approach, the mound was considered an appealing asset.

In the summer of 1931, when word of the planned destruction of the large mound got out, archaeologist Winslow Walker of the Smithsonian Institution hurried to Jonesville to assess the situation even as the bridge contractor began working day and night with a steam shovel to level the mound. Walker returned with his WPA field crew in November, but they were rained out and could not continue excavations until September 1932. By then, the large mound had been leveled almost to the ground. Walker’s limited salvage work, however, provided the core of archaeological knowledge about the Troyville site. In the earthworks, he found intriguing features, such as packed layers of multicolored clays interspersed with thick, crisscrossed layers of native cane. Evidence surfaced of a stepped-ramp on the large mound and various post-supported structures. An assemblage of potsherds was recovered, as were remains of flora and fauna. Animal bones—including those of deer, squirrels, turtles, fish, turkeys, and waterfowl—were unearthed. Thirty-eight species of plant material were identified. For the remainder of the twentieth century, archaeologists who reviewed Walker’s report concluded that destruction of the site was so thorough as to preclude the value of additional investigation.

A Fresh Look at the Old Site

Beginning in 2003, Joe Saunders and Reca Jones with the Louisiana Regional Archaeology Program took a fresh look at the Troyville site using minimally invasive soil coring and mapping. When considered with earlier findings, their data added and confirmed important details of the mounds:

Mound 1 – The mound is presently eight feet high, two hundred feet long, and ninety feet wide. A historic cemetery exists on the east side. Prehistoric human bones found during historic burials, suggest the mound may have been built originally for entombments.

Mound 2 – The mound has been mostly destroyed by construction. In 1896 the dimensions of the mound were listed as fifteen feet high, ninety feet long, and seventy-five feet wide, with a dome-shaped top. One human burial was discovered in the mound.

Mound 3 – The mound has been destroyed by residential construction, but about thirty inches of the mound base survives.

Mound 4 – This mostly destroyed mound was 164 feet square. Coring revealed pit features and a post that hints of a wooden palisade around the mound. A pit contained the pieces of at least thirty different ceramic vessels and suggests that communal activities may have occurred here.

Mound 5 – Historically documented at eighty feet tall, with a base of 180 feet square, Mound 5 had a second smaller platform topped with a conical mound. By 1882 the top two layers were mostly destroyed to fill nearby depressions. Most of the remaining mound served as fill material for the bridge approach (approximately 21,000 cubic yards). Coring revealed that from three to six feet of mound deposits remain beneath buildings that now cover the site. Cane from the mound was radiocarbon dated from AD 679 to 778.

Mound 6 – This mound was 131 feet long and ninety-eight feet wide. It was destroyed by 1900.

Mound 7 – The mound was leveled to build a modern boat launch facility. Some midden materials still exist on the site.

Mound 8 – Presumably located on the bank of Little River and capped with a historic cemetery (based on early reports), this mound has not been located.

Mound 9 – This mound was 131 feet square, and its remnants are now beneath a house.

Beginning in 2005, Aubra Lee excavated part of the levee-like embankment and a site near the Black River. Her research showed that the embankment was about fifty feet wide at its base and still more than three feet tall. At one time the feature was the site of round structures up to twenty-six feet in diameter and contained pits of various types. Midden material unearthed at the Black River site on different occasions included pieces of sixty-one pottery vessels, bones of turtle and deer, and three human burials comprising twelve individuals. Evidence of two round structures was also located there. Some plant and animal remains were revealed.

There is no comparable example of wanton destruction of a world-class archaeological site in America. The owner of the largest mound reportedly sold its dirt to the bridge contractor for one hundred dollars. Gone is the opportunity to learn more about the builders—who they were, their culture, why they chose this site, and why they left. The history of the Troyville site after Euro-American contact represents a sad case of lost cultural treasures.