Jim Crow & Segregation

In the late nineteenth century, the implementation of Jim Crow—or racial segregation—laws institutionalized white supremacy and Black inferiority throughout the South.

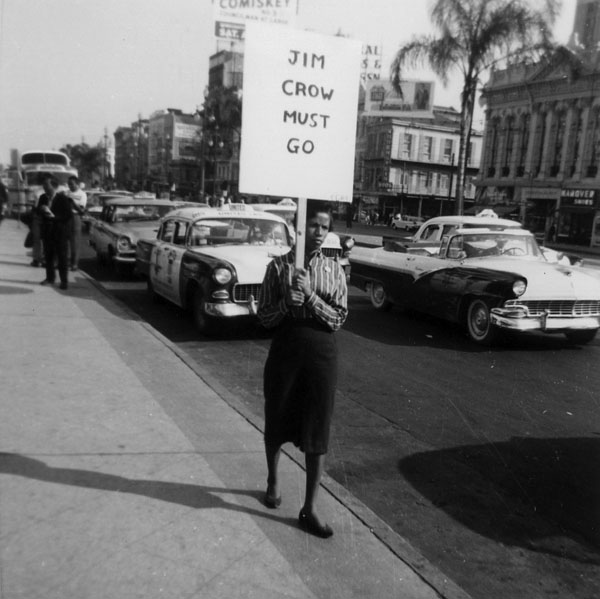

Courtesy of the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University.

A black and white reproduction of a photograph of a New Orleans CORE protest at Woolworths and McCrory's on Canal Street, April 1961.

In the late nineteenth century, many white Louisianans attempted to reverse the gains African Americans had made during Reconstruction. The implementation of Jim Crow—or racial segregation laws—institutionalized white supremacy and Black inferiority throughout the South. The term Jim Crow originated in minstrel shows, the popular vaudeville-type traveling stage plays that circulated the South in the mid-nineteenth century. Jim Crow was a stock character, a stereotypically lazy and shiftless Black buffoon, designed to elicit laughs with his avoidance of work and dancing ability. By 1880, however, “Jim Crow” came to signify a model of race relations in which African Americans and white Americans operated in separate social planes. Almost one hundred years would pass before civil rights workers were able to reverse these laws.

The Origins of Jim Crow, 1865 to 1890

In the five years after the Civil War, the Republican-controlled Louisiana Congress enacted powerful civil rights legislation aimed at securing African Americans their political rights. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, respectively, abolished slavery, recognized African Americans as citizens, and guaranteed African American men the right to vote. The Fourteenth Amendment was particularly significant because it guaranteed African Americans the same rights of citizenship that white Americans had, including equal protection under the law. By 1875 African Americans across the South, supported by the federal government, had established nearly four thousand schools for Black students. In addition, more than fifteen hundred had run for office as state and national representatives.

Instituting Jim Crow was a gradual process before 1880, especially during Reconstruction, when it appeared that African Americans enjoyed some protection from the federal government. But in 1865, the Louisiana legislature began implementing “black codes,” laws that formed the basis for racial segregation. Originating in the eighteenth century, black codes regulated and restricted the movement of enslaved people. More generally, they reinstated the antebellum southern social order, in which white people occupied a higher social rung than Black people. Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, black codes limited Black life in numerous ways. They determined the types of businesses African Americans could own and the time of day they could visit downtown. The codes stipulated that no more than three African Americans could ever assemble in one place, and gave white people legal authority over Black people when no police officer was present. Though black codes were found in every parish, they were most vigorously enforced in the northern and eastern parishes of Louisiana.

In southern Louisiana, African Americans were allowed much more freedom, largely owing to the racial demographics of southern Louisiana in general and New Orleans in particular. By 1860, New Orleans could be divided into three discernable racial groups: whites, free people of color, and enslaved people of African descent. In New Orleans, free people of color, who often had a mixed racial heritage, traditionally enjoyed a measure of freedom in their businesses and social interactions not found in other parts of the state.

By 1877, deepening distrust between white people and African Americans led to the lowest point in race relations in American history. At the beginning of Reconstruction, Louisiana sent several Black politicians to the US House of Representatives, and one African American, P. B. S. Pinchback, served as governor from late 1872 to January 1873. By the time federal troops were officially removed from Louisiana in 1877, however, all of these politicians had been defeated; all hopes for improved racial relations, or federal intervention on behalf of Black Louisianans, seemed to have evaporated.

As Reconstruction ended, most African Americans in Louisiana rented small plots of land, hoping to become self-sufficient farmers. Formerly enslaved people tended to stay geographically close to their former owners, usually living no more than fifty miles away. In place of slavery, white Louisianans developed an agricultural system called sharecropping. White property owners gave African American farmers access to land with the understanding that these farmers would give the landowner part of the crop as “rent.” Sharecropping quickly evolved into an exploitative relationship between farmers and landlords. Often illiterate and uneducated, sharecroppers rarely understood the written contracts they were compelled to sign. Further, landlords set the price of the crop, often ignoring its market value, while Black farmers with left without recourse. Sharecropping undergirded Black poverty in Louisiana—profits were scarce, weather and climate were often uncooperative, and corruption was rampant. While there were attempts to unify white and Black farmers in the immediate postbellum period, sharecropping allowed class and racial distinctions to persist.

Institutionalizing Jim Crow

By 1890, the Democratic Party hatched a scheme to completely remove the Republican Party from the South by disfranchising southern Black men, the most ardent supporters of the Republican Party. White Louisianans implemented poll taxes, literacy tests, residency requirements, and “understanding” clauses to prevent Black people from registering to vote. Despite the rights guaranteed them by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, African Americans were systematically excluded from the political process. Social segregation soon followed.

In 1891, the Louisiana legislature had officially segregated the railroads within the state. In 1892, Homer Plessy, an active member of a New Orleans civil rights organization, the Comité de Citoyens, bought a first-class ticket on a train and attempted to sit among whites. After he was arrested for breaking the law, Plessy sued the railroad company, his lawyers arguing that segregation denied him equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1896, however, the US Supreme Court upheld Louisiana law in its decision on Plessy vs. Ferguson. Speaking for the majority, Justice Henry Brown stated that segregation did not deprive Plessy of his rights, nor did it make him an inferior person. The justices argued that states could establish “separate but equal” facilities; if Black and white people were treated equally, segregation would be allowed to stand. Yet, in almost all public facilities—schools, hospitals, trains, restaurants, hotels, parks, cemeteries, the armed forces, and jury duty—white people received priority over African Americans. Following the decision, some institutions excluded African Americans altogether.

Two years after the Plessy decision, Louisiana passed one of the first laws officially stripping Black men of the right to register to vote. In essence, everything that could be segregated in Louisiana was. Public facilities for adults, including restaurants, hotels, night clubs, and cemeteries, were strictly segregated, as were public facilities for children such as amusement parks, playgrounds, and schools. By 1900, the line separating white and Black people had become deeply entrenched in Louisiana’s culture. After 1902, New Orleans streetcars were segregated. A 1908 state law prohibited cohabitation (in marriage or domestic situations) between white and Black men and women. Racial segregation in jails was required in 1920. Even in New Orleans, tolerant (if not friendly) interactions between white and African American residents all but disappeared. The Catholic Church established a segregated parish in downtown New Orleans, the Congregation of Corpus Christi.

Not coincidentally, lynchings increased dramatically after 1900, primarily in the northern parishes of Caddo, Ouachita, and Morehouse. Between 1900 and 1931, more than half the lynchings in the state occurred north of Alexandria. The numbers of African Americans lynched are in the thousands, though detailed statistics are skewed because police officers in the northern parishes rarely considered lynchings as homicides. Still, lynchings and the threat of lynching contributed to the maintenance of Jim Crow.

The Civil Rights Movement Builds

As the century turned, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) became increasingly active in Louisiana. Between 1909 and 1930, the NAACP was a decentralized organization that focused on ending lynchings. In the 1930s, however, the organization retooled itself for the purpose of challenging the doctrine of “separate but equal” that formed the base of the Jim Crow laws.

In 1930s Louisiana, the NAACP counted New Orleans attorney A. P. Tureaud as one of its most important assets. Tureaud, a Howard University Law School graduate and colleague of Thurgood Marshall, sought to dismantle segregation in Louisiana’s public schools. Tureaud believed that segregated education, and the meager resources allotted for African American children, perpetuated poverty and inequality across generations. With the assistance of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Tureaud sued the state of Louisiana for paying African American teachers lower salaries than their white counterparts. Tureaud’s 1940 victory in Joseph P. McKelpin v. Orleans Parish School Board led to pay equity among all public schools.

World War II ushered in a number of legal and social changes that further weakened the structure of segregation. Nearly one million Black men and women served in the armed forces, and about five hundred thousand served in Europe and Asia. African Americans understandably believed that their willingness to die for their country abroad proved their worthiness for expanded political rights at home. Faced with an emergent civil rights movement, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981 in 1948, fully desegregating the armed forces.

In Louisiana, the fight for desegregation took place in another social arena: public accommodations. Long before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, Alabama, African Americans in Baton Rouge initiated a bus boycott of their own in 1953. Baton Rouge segregated the buses so that the first ten rows were reserved for white passengers, though African Americans accounted for 80 percent of the riders. A leading minister in the city, T. J. Jemison, spoke before the Baton Rouge City Council, testifying that it was unfair to force African American riders to stand in the back of the bus while the seats in the front remained empty. In June, African Americans in Baton Rouge formed the United Defense League (UDL) and organized a bus boycott. After one week, the city council and the UDL reached a compromise. The first two rows on the buses were reserved for white passengers but, after that, African Americans could sit where they wanted. Though segregation was still in effect, the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott provided a model for other cities to follow.

Memorable and vital successes over racial segregation continued in Louisiana and the rest of the South throughout the 1950s and 1960s. In response to a pending lawsuit, segregation was abolished at Louisiana State University; the first African American undergraduate enrolled in 1953. The Plessy decision was finally overturned the next year, when the US Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The court found legal segregation unconstitutional in all public accommodations, especially public schools. Though met with massive resistance, the decision transformed the southern way of life. The “whites only” screens on New Orleans’s streetcars were officially removed in 1958. In 1960, the New Orleans School Crisis erupted over the desegregation of public schools. But in 1961, desegregation continued peacefully.

Jim Crow’s Demise

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act outlawed racial discrimination and segregation in schools, restaurants, hotels, and universities. Signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Civil Rights Act also prohibited unequal application of voting requirements, ended discrimination in interstate commerce, barred discrimination by state and city governments, and outlawed discrimination in private companies that take federal dollars. The 1965 Voting Rights Act went a step further and outlawed numerous tactics used to disenfranchise African Americans and other groups. Officially, the era of Jim Crow had ended. After nearly one hundred years of economic, political, and social demoralization, African Americans occupied the same levels of citizenship as white people, at least in the eyes of the law.

For Louisiana, desegregation in public schools would come slowly. In 1965, only five Louisiana parishes submitted plans for integration. By 1967, thirty parishes still had made no arrangements to desegregate. In 1970, forty-five parishes were ordered to come up with a legitimate plan or risk the loss of federal funding; full integration of Louisiana’s public schools did not come until the mid-1970s. Similarly, Louisiana was ordered—on at least ten occasions between 1965 and 1998—to integrate segregated universities and professional schools or compensate the state’s historically Black colleges and universities for generations of neglect.

The impact of segregation on Louisiana’s culture and history continues to linger. One lasting consequence of Jim Crow is the persistence of extreme poverty among African Americans, particularly in the northern parishes bordering the Mississippi River. The decline of cotton and sugar production, the source of Louisiana’s wealth prior to the Civil War, has left behind impoverished communities unable to find suitable alternatives. In twenty-first century, “stealth racism,” or subtle long-term racism, remains in Louisiana, particularly as racial attitudes harden in the midst of economic instability.