Geographer's Space

One Night in Louisiana

Abe Lincoln’s bloody melee

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: February 7, 2021

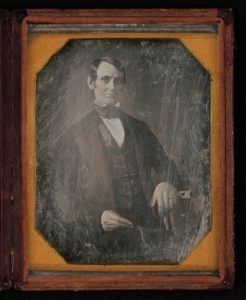

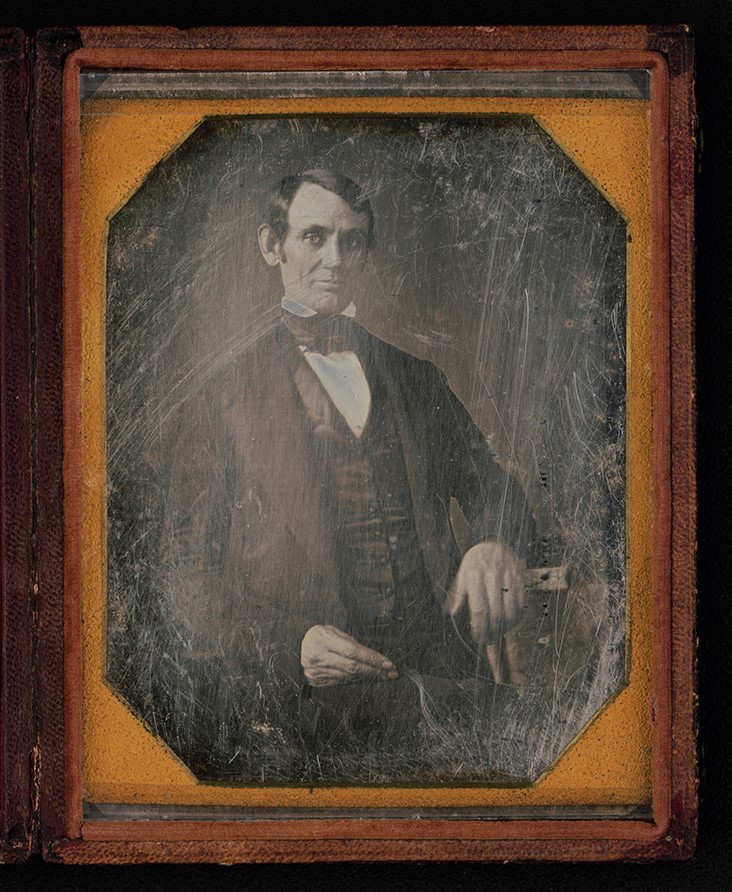

Photo by Nicholas H. Shepherd; Library of Congress

The earliest known photograph of Lincoln, then a representative-elect, ca. 1847.

“[O]ne night they were attacked by seven negroes with intent to kill and rob them. They were hurt some in the melee, but succeeded in driving the negroes from the boat, and then ‘cut cable’ ‘weighed anchor’ and left.”

That’s all Abraham Lincoln wrote, in an 1860 autobiography scribed in the third person, of an assault he and his boatmate endured in Louisiana in 1828. The incident is a provocative footnote in the much-studied life of the Great Emancipator—poignant for its tragic irony and commentary on the contingencies of history. The nature of the journey and the exact location of the attack have both been shrouded in mystery, but various clues shed some light.As was typical of Western youth of the era, nineteen-year-old Abe Lincoln took a job building a flatboat at Rockport, Indiana, and guiding it down to New Orleans with a neighbor named Allen Gentry to sell farm produce, intending to return by steamboat. By my best estimates, the twosome launched into the Ohio River in mid-to-late April 1828, entered the Mississippi River four days later, and floated past what are now East Carroll, Madison, Tensas, Concordia, and Pointe Coupee Parishes during early May. Shortly thereafter, they entered what Lincoln called the “sugar coast” of lower Louisiana, where they “lingered” for roughly a week, selling or trading upcountry produce such as corn, smoked hams, and barrel pork.

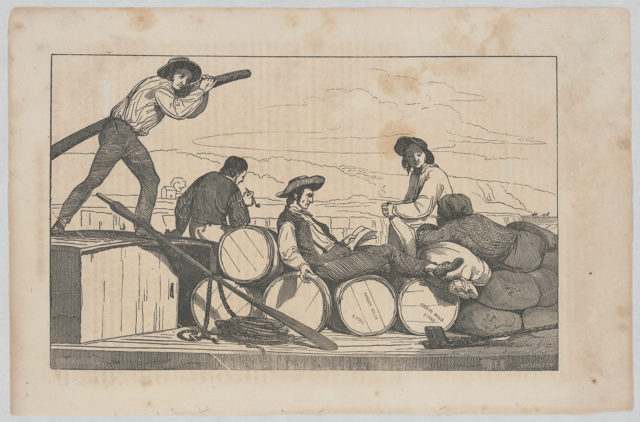

Men pile atop flatboat cargo in an antebellum engraving by Alexander Anderson. Library of Congress

Approximately sixty miles above New Orleans, Gentry and Lincoln tied up for the night of May 12 or 13. Nocturnal navigation was risky, especially in this high river, and amateurs like Gentry and Lincoln knew to anchor at dusk and sleep along the banks.

That’s when the attack occurred.

The melee was likely more violent than Lincoln, a man of few words prone to understatement, indicated in that 1860 passage. Biographer William Dean Howells’s account is worth quoting because Lincoln personally approved its wording: “One night, having tied up their ‘cumbrous boat,’ near a solitary plantation on the sugar coast, they were attacked and boarded by seven stalwart negroes; but Lincoln and his comrade, after a severe contest in which both were hurt, succeeded in beating their assailants and driving them from the boat. After which they weighed what anchor they had, as speedily as possible, and gave themselves to the middle current again.”

Indiana townsfolk interviewed by William Herndon in 1865 readily recalled the incident. Historians Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis published Herndon’s 1865 interview notes in a 1997 book titled Herndon’s Informants, where may be found more attack clues. “Lincoln was attacked by the Negroes,” neighbors recalled; “no doubt of this—Abe told me so—Saw the scar myself.—Suppose at the Wade Hampton farm or near by—probably below at a widow’s farm.” Anna Gentry shed more light on the incident, which her future spouse Allen (by now deceased) had experienced firsthand: “When my husband & L[incoln] went down the river they were attacked by Negroes—Some Say Wade Hamptons Negroes, but I think not: the place was below that called Mdme Bushams Plantation 6 M below Baton Rouche—Abe fought the Negroes—got them off the boat—pretended to have guns—had none—the Negroes had hickory Clubs—my husband said ‘Lincoln get the guns and Shoot[’]—the Negroes took alarm and left.” John R. Dougherty, an old friend of Allen Gentry, said “Gentry has Shown me the place where the [negroes] attacked him and Lincoln. The place is not Wade Hamptons—but was at Mdme Bushans Plantation about 6 M below Baton Rouche.”

We have three waypoints in locating the attack site: (1) a plantation located below Wade Hampton’s place, specifically one (2) affiliated with a woman named “Busham” or “Bushan,” (3) located around six miles below Baton Rouge.

Wade Hampton’s sugar plantation in Burnside remains famous today as Houmas House, refurbished around 1840 but with an older structural frame. Just below the Hampton place, we seek a woman-affiliated plantation whose surname sounded like “Busham” or “Bushan.” Neither the 1829 parish census, nor the 1830 federal census, nor detailed plantation maps of 1847 and 1858 record either such surnames or a woman-led household in the specified location.

But Herndon apparently gleaned additional information that did not appear in his interview notes, because when he published Herndon’s Lincoln in 1889, he reported “the plantation” belonging not to “Busham” or “Bushan,” but to the rhyming “Duchesne”—specifically “Madame Duchesne.” That surname also fails to appear in the aforementioned sources.

Yet there was a Duchesne woman in this area: French-born Rose Philippine Duchesne, who in 1825 founded the Convent of the Sacred Heart (St. Michael’s) in present-day Convent, located twelve miles below the Hampton Plantation. Duchesne established Catholic missions for the Society of the Sacred Heart throughout the St. Louis area and south Louisiana; people called her “Mother Duchesne,” and the institutions she founded became known as “Mother Duchesne’s convent,” “Mother Duchesne’s school,” etc. (Mother Duchesne was canonized a saint by the Catholic Church in 1988 and is entombed in a shrine in St. Charles, Missouri.)

It is plausible that the property affiliated with the woman named “Busham,” “Bushan,” or “Duchesne” was the convent of Mother Duchesne. Gentry and Lincoln may have heard that name from river traders, and reasonably assumed it was a plantation, notable because it was “owned” by a woman. The convent itself resembled a large plantation house, at least to newcomer eyes. Mother Duchesne’s convent, after thirty-seven years of Indiana storytelling, became “Mdme Bushans Plantation.” No other explanation has come to light.

We have one final problem in situating the incident: Wade Hampton’s plantation is not six miles below Baton Rouge, but sixty river miles. This I cannot reconcile. Perhaps, as Indiana storytelling over many years seems to have converted “Duchesne” to “Bushan,” it also may have shifted “sixty” to “six.”

The preponderance of evidence suggests Lincoln and Gentry were attacked near, of all things, a convent and Catholic girls’ school founded by a future American saint. We can say with greater confidence that the melee occurred near Convent, within St. James Parish, sixty or so miles downriver from Baton Rouge, on the east bank of the river.

Who were the attackers? My sense is they were maroons, escaped slaves who took to the swamps to find freedom. They were probably after food and not money; everyone knew flatboatmen heading downriver had edibles on board but little if any cash, as earning income was the whole intent of their journey. On an ethical level, it may be said that the bloody clash produced not seven culprits and two victims, nor vice versa, but rather nine victims—victims of the institution of slavery and the violent desperation it engendered.

Some say Lincoln received a lasting scar above his right ear from the fight; others say it could be seen above his right eye, although one is not readily apparent in photographs. It is no exaggeration to say that Lincoln came close to being murdered in Louisiana, the night before he would first set foot in New Orleans. The incident may also explain a story that Lincoln had acquired, during his New Orleans trip, “a strange fixation—that people were trying to kill him.”

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and a forthcoming book on the West Bank. Material in this column was drawn from Campanella’s 2010 book, Lincoln in New Orleans, where readers may find more information and sources. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.