Latest

“Operation Ouch”

A look back at past mass-vaccination campaigns in Louisiana

Published: March 25, 2021

Last Updated: April 21, 2021

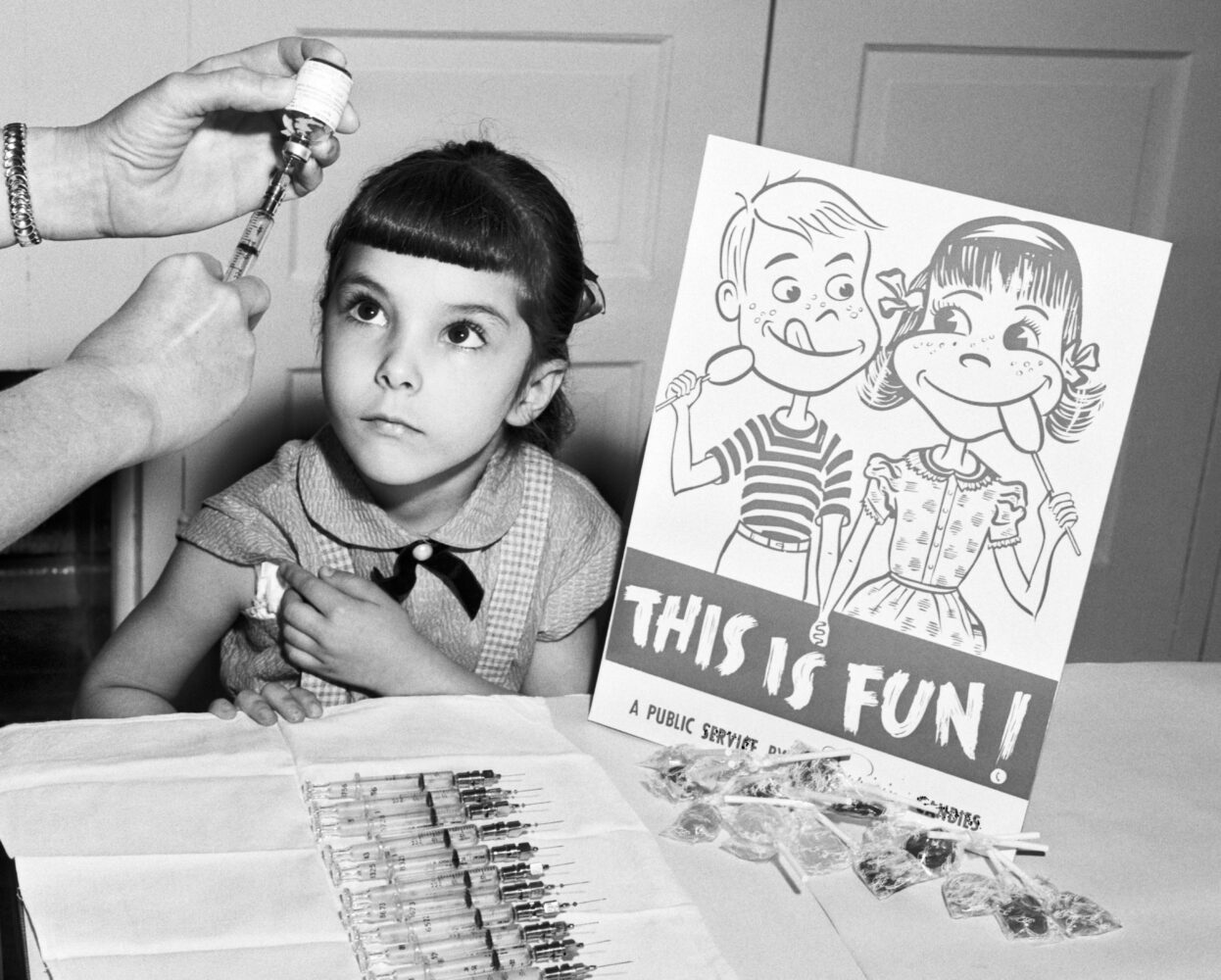

Classic Stock / Alamy Stock Photo

A little girl awaits her polio vaccine.

March 26, 2021.

On a sunny Sunday in East Baton Rouge Parish, the Boy Scouts of Istrouma continued to do their civic duty for public health. The previous weekend, Scout troops had papered the area with posters urging residents to come and get a vaccine, and on this day, they fanned out in groups of six, scheduled in two shifts, to assist at the 36 area vaccination stations set up at elementary and high schools, on LSU and Southern University campuses, and at two local television stations. According to the Baton Rouge Advocate, at each site the Scouts helped direct traffic, herded people toward the correct entrances, and made themselves available to run errands for the doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other adult volunteers handling registration and administering doses of vaccine. That Monday, the paper’s front page trumpeted that the effort had been a rousing success: 154,000 Louisianans had been vaccinated in East Baton Rouge Parish. Not only that, but similar mass-vaccination drives in neighboring parishes that day had inoculated an additional 44,200 souls, bringing the total for the five-parish area to just under 200,000 doses—a number representing almost two thirds of the total population.The scene above isn’t from the era of publicly available COVID-19 vaccinations, which began in early 2021, but from nearly sixty years in the past. In October 1962, when the Boy Scouts showed up to do their duty, Louisiana was joining a massive nationwide effort to disseminate a new polio vaccine through public campaigns like the one described in the Morning Advocate. (The liquid vaccine was administered orally, on a sugar cube or in a sugar solution, which must have helped, since children were the main demographic targeted to receive it. In the Advocate article that reported the Scouts’ effort, a representative from the March of Dimes urged: “Make a date now … and drink a small amount of pleasant-tasting vaccine.”)

Throughout the past year, as the novel coronavirus ravaged the planet, historians, journalists, and other people whose job it is to make sense of things have investigated and written about previous epidemics—from smallpox to the deadly 1918 influenza to HIV/AIDS—to craft a framework for understanding how this contemporary plague has affected us, practically as well as culturally. Now that the vaccine rollout for a new virus has begun, a natural response is to look at past mass inoculation efforts.

Vaccines made by the Pfizer and Moderna drug companies for COVID-19 received emergency use authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2020 and began distribution through hospitals and pharmacies to Americans deemed most at risk of contracting COVID-19 (or of suffering the most or dying from an infection), such as front-line healthcare workers and the elderly. In late February, about a year after the new virus had first infiltrated Louisiana, a third vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson was also given emergency use authorization. (EUA is a category developed in the 21st century as a common-sense response to public health crises, when it makes sense to expedite dissemination of a drug that has proven itself effective and safe by FDA standards, but has not gone all the way through the regulatory body’s formal, lengthy dot-all-i’s and cross-all-t’s approval process.)By time the Johnson & Johnson vaccine gained its EUA designation, Louisiana had already begun considering the logistics of higher-volume vaccine rollouts, using spaces like the former Zephyr Field stadium in Metairie and the New Orleans convention center, as well as civic centers in Monroe, Rayne, and Lake Charles to get shots into the arms of hundreds or thousands of Louisianans in a conveyor-belt style, not dissimilar to the way the oral polio vaccine was distributed in the early ’60s. A mass vaccination event staged at the Alario Center in Jefferson Parish had jabbed about 500 on February 9, eleven months after the first case of COVID-19 had been identified in Louisiana.

The practice of inoculation in the West is roughly as old as the United States. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington ordered soldiers in the Continental Army inoculated against smallpox, when the process was still fairly rough and unreliable. Called variolation, it involved introducing live viral matter (basically pus) from a pox blister into a cut in a person’s arm, which usually resulted in a pretty mild case of pox and then immunity. About twenty years later, English doctor Edward Jenner developed what’s thought of as the first true vaccine by fine-tuning that process to be less deadly and frightening: in 1796 he began inoculating patients with live cowpox virus, a much less dangerous disease that also left people immune to smallpox (and from whose Latin name, vaccinia, the name for the prophylactic is derived.) The first mass vaccination campaign in the Americas, in 1803, used Jenner’s method, which was still rustic and unpleasant. A group of about twenty-two orphans set sail from Spain to Mexico, and during the long trip, they kept the viral matter alive like a hot potato. One boy would be inoculated, and as he developed pox blisters, lymph from the pustule would be transferred to the next, keeping the culture alive. When the ship arrived in Mexico, the oozing viral passenger was transferred to a group of children there, and in that grisly way nearly 100,000 people in Latin America and the Caribbean were inoculated.

Smallpox was the scourge that kept the idea of vaccination in the popular consciousness for most of the 19th century and into the beginning of the 20th. It wasn’t uncommon to see ads in New Orleans’s Daily Picayune for private smallpox vaccine vendors. In 1842, for example, a B. W. Cohen (no medical title) ran a classified ad for his new “vaccine institution” at no. 5 Carondelet Street, writing, “having for the last seven years resided in New York, where he constantly supplied the most of the medical practitioners, he is able to promise to the public that they may always depend upon him.” Mr. Cohen’s ad promised that those who could not pay would be vaccinated for free; for comparison, a similar Daily Picayune ad from 1894 priced vaccines at between ten cents and one dollar, or between about three and thirty 2021 dollars. (The variation in price depended on how many times—between one and ten—the patient wanted to get stuck with a quill delivering dried virus.)

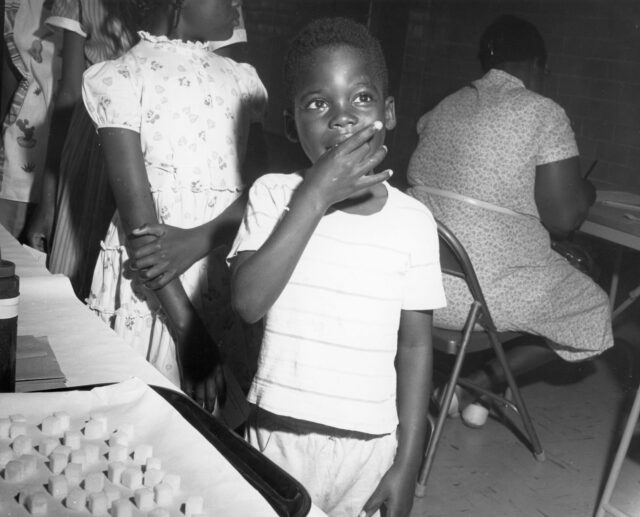

Child taking the sugar lump Sabin vaccination for polio immunization, 1967. Photo by United States Public Health Service. Courtesy of RBM Vintage Images / Alamy.

In the early 1950s, polio rates in the US spiked. In 1952, the year virologist Jonas Salk developed his injectable vaccine for the disease (another researcher, Hilary Kropowski, had found an oral vaccine to be successful two years earlier) infection numbers hit 58,000, with over 3,000 deaths and more than 20,000 survivors suffering some level of ongoing paralysis. In 1954, the US rolled out a mass vaccination effort with Salk’s product that was actually a huge trial, with nearly two million children in forty-four states receiving either vaccine, placebo, or nothing, as a control group.

“One million second graders to get shots next year!” announced the New Orleans Times-Picayune, describing a December 1953 visit from Elaine Whitelaw, director of women’s activities for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (which later became the March of Dimes). Speaking at the Roosevelt Hotel, Whitelaw explained that “The vaccine is an accomplished fact… its safety is without question. But complete proof of its validity will depend on these wholesale tests.” In early March 1954 about 12,500 children, selected by the Louisiana Board of Health in Caddo, Bossier, Rapides, and East Baton Rouge Parishes, were set to participate in those tests. Caddo had been among the parishes hit hardest by polio. The Shreveport Medical Society and both the Caddo and Bossier school boards, as well as the Shreveport District Nurses Association, pledged to collaborate on the vaccine rollout. So did a committee of volunteers, largely made up of mothers, who organized informational meetings and coordinated logistics. The timing caused some anxiety in Shreveport, where school let out for the summer on May 28. Would there be enough time to vaccinate more than 6,000 second graders at school, which was the plan, when the full course of Salk vaccine took five weeks? (The last dose was given to the Caddo-Bossier cohort on June 2, 1954. Students had to trek back to school after summer break had started for their final immunization.)

Momentum for the trial looked as if it might stutter when Walter Winchell, whose radio and television simulcast reached tens of millions, announced on-air on Sunday, April 4, that the Salk vaccine, which deployed dead virus, “may be a killer.” Following the broadcast East Baton Rouge Parish first postponed and then actually bowed out of the trial, although the Louisiana State Board of Health did its best to send reassuring messages. Dr. King Rand of Alexandria, vice-president of the board, was more direct: he told the Alexandria Town Talk that Mr. Winchell’s commentary was “asinine.” Dr. W. J. Sandidge, director of the Caddo-Shreveport Health Unit and a key organizer of the vaccine trial, appeared on Shreveport’s KSLA news channel to attempt to quell local nervousness, which seemed to work: in mid-April, he told the Shreveport Times that he expected parental consent for the vaccine to range from 75–97 percent per school. His counterpart, Bossier’s Dr. H. H. Barnett, projected similar figures.

Steven’s 14-year-old brother Jack had contracted polio three years before and was still in treatment. When his brother was vaccinated, Jack was at the Shrine Hospital in a body cast.

On April 27, 1954, the Times ran a photo of Sandidge and Barnett accepting a delivery of vaccine from New Orleans. Two days later, the paper pictured 7-year-old Steven Murray getting stuck at the Creswell Street School. (“I didn’t mind a bit,” he told the reporter, though his startled face in the photo hinted otherwise.) It was a particularly special day for the Murray family; Steven’s 14-year-old brother Jack had contracted polio three years before and was still in treatment. When his brother was vaccinated, Jack was at the Shrine Hospital in a body cast.

The vaccination sites for that 1954 campaign were part of the segregated public school system, as were the eighty-six schools in the same region participating in a Sabin oral vaccine drive nearly ten years later, in March of 1963. Racial bias in the American response to polio had long been a problem, with segregated hospital and rehabilitation facilities providing blatantly unequal resources. This was in part due to pervasive American medical racism and in part due to a specific errant belief as to who the disease threatened most. As late as 1951, when a cluster of about 150 cases originated among Shreveport’s Black population, the United Press wire framed it as “unusual,” breaking one of the disease’s “rules”—that it affected white patients more often and more severely than their Black peers.

Just over 2,600 students in the Shreveport area got the Salk trial on Wednesday, April 28, 1954, as well as a “Polio Pioneer” button to affix to their lapel and a card for their wallets as part of what the newspaper called “Operation Ouch.” “White doctors will administer the serum in white schools and Negro doctors in Negro schools,” explained the Times in advance. Thirteen Black schools in Shreveport were used as vaccination sites, with Black kids from rural areas bused in on that Wednesday. The paper estimated that about 710 shots would be given to that population, though after the fact they didn’t report a breakdown by race. In Bossier, shots were given to white kids on Wednesday and Black kids on Thursday; the Times announced that 470 out of 718 eligible white children had been vaccinated, and that up to 538 Black children could receive the shots on day two. Notably, the paper reported that as few as 75–80 of those eligible Black children had signed up in advance, though after the drive, doctors were quoted as saying there had been a marked increase over what was expected in terms of “rural Negro” schoolchildren showing up for their shots.

In April 1955, the huge trial was declared successful. Headlines blared it around the country, and mass vaccination efforts continued. A tragic setback came early in the official rollout, when a huge polio outbreak in the West and Midwest was traced back to a defective batch of Salk vaccine made by Cutter Laboratories, but it didn’t seem to affect Louisiana’s confidence in the product it was receiving from other laboratories like Eli Lilly. In September of that year, for example, children between ages five and nine could get a free shot every Thursday at City Hall in Eunice, every Wednesday in Bunkie, and every Friday in West Carroll, depending on their inoculation schedule. By October 1, the state planned to have clinics in every parish distributing the vaccine, which had already been administered to nearly eight million children worldwide.

Still, public enthusiasm for the Salk shot waned after the Cutter Labs incident, and when Albert Sabin’s oral vaccine—the pleasant-tasting one that the Boy Scouts helped out with in East Baton Rouge Parish in 1962—was approved, it became the favorite. That Scout-assisted drive was part of a new push for mass vaccination in the early ’60s, following passage of the Vaccination Assistance Act of 1962—a formal, federally-supported immunization effort meant to counter measles, smallpox, tetanus, and diphtheria as well as polio by providing cash grants, doses, and direct organizational and staffing support to states and cities. (This followed a bill passed in 1955 under the Eisenhower administration that sent thirty million dollars to states for purchasing vaccines.) In 1964 and ’65, the Louisiana Vaccination Assistance Project sent teams of health workers to survey the state of the state’s immunity, checking for rates of up-to-date vaccination across Louisiana under the auspices of the state Board of Health and the Vaccination Assistance Act.

Although a state-sponsored push for the measles vaccine also rolled out en masse in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and the smallpox effort ran slowly but steadily for more than a century, the polio campaign comes the closest to the towering challenge Louisiana (and the US, and the world) is taking on in 2021 as it faces down COVID-19. Many elements stay consistent, like celebrities promoting the effort (Elvis, that Louisiana Hayride-minted star, got his Salk shot live on The Ed Sullivan Show) and anti-vaccination suspicion (the Daily Picayune ran editorials shaming smallpox vaccine skeptics yearly for the first decade of the twentieth century, years before Walter Winchell nearly derailed the Salk trials.) Systemic challenges to healthcare access along racial lines also persist. In early March 2021, the Louisiana Department of Health (LDH) reported that far fewer Black Louisianans were receiving COVID-19 vaccinations than white ones, prompting them to launch a new grassroots campaign, “Bring Back Louisiana #SleevesUp,” to promote more equitable distribution, with community partners including the Louisiana NAACP and the Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus, with plans for phone-banking, in-person canvassing, and large-scale community vaccination events.

In Louisiana, even when facing something as serious as a heart attack (or a pandemic) people still also respond with a dose of local humor. In the ’60s, the Opelousas Daily World ran a regular column of funny news tidbits, local gossip, and observations. During the Sabin vaccine campaign of 1963 it offered this gem under the heading “This & That”: “On a Sunday afternoon at a school in a neighboring town, a small girl was standing in line to get her final polio oral vaccine. Her girlfriend standing close by was prattling away about this and that. ‘My mama was not going to take the polio sugar,’ she said, ‘until the doctor told her that a grown person might be a carrier.’ The first little girl looked at her intently for a moment and finally answered, ‘My mama was a Carriere before she married papa.’”

A columnist since 2016, Alison Fensterstock has written for 64 Parishes about music, dogs, witches, hippies, and other things.