Summer 2021

Louisiana and the Defender

How Chicago’s legendary newspaper inspired migrants and amplified local journalism

Published: May 27, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

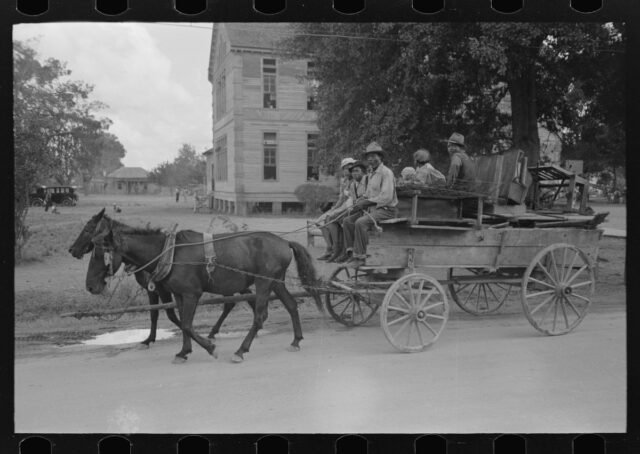

Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress

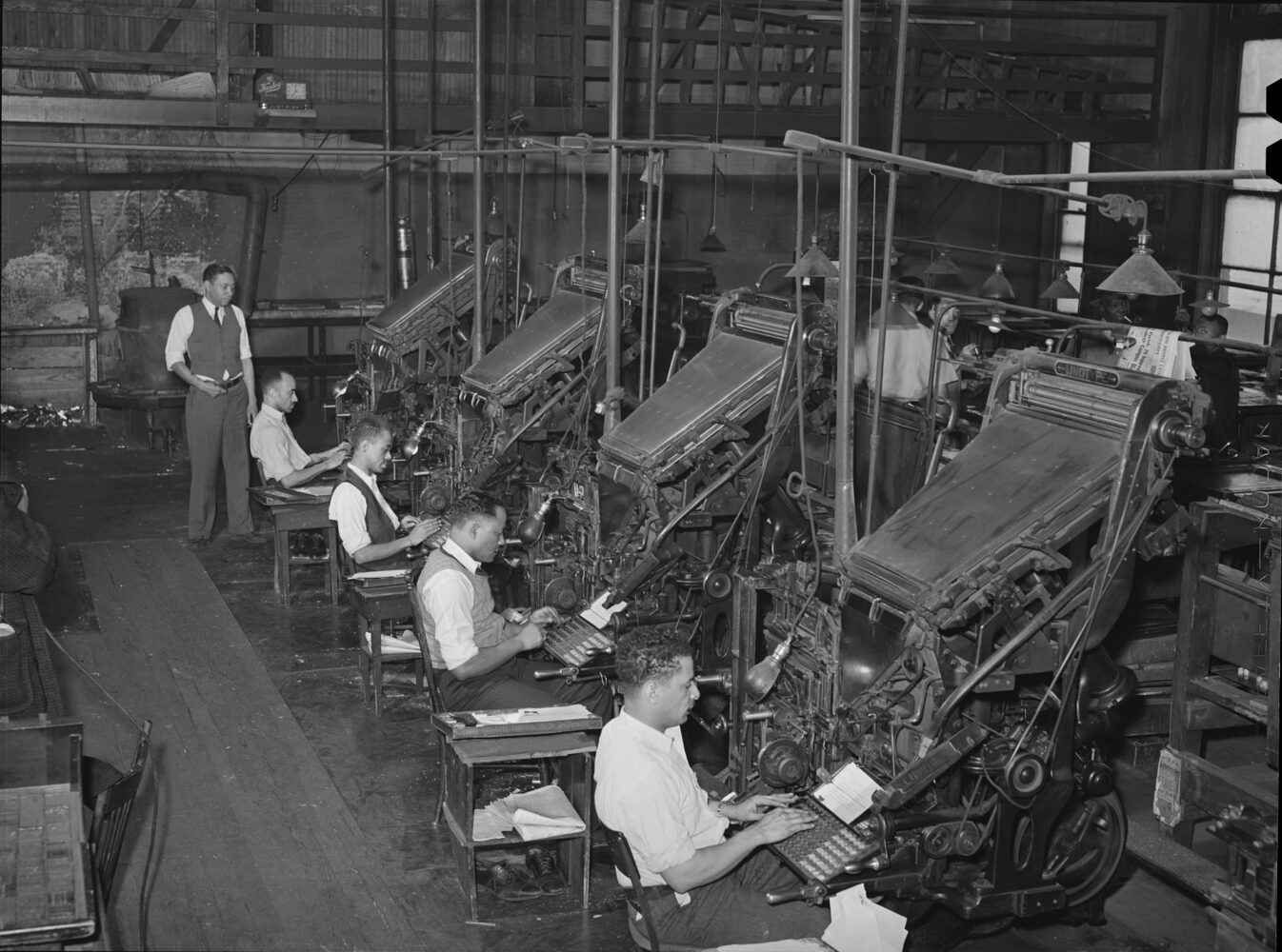

Chicago Defender’s linotype operators, 1941.

The Defender was founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott, a Georgia native whose parents had been enslaved. Blessed with a formidable intellect and a great reserve of tenacity, Abbott had first visited Chicago for the 1893 World’s Fair and Columbian Exposition while he was a student at the Hampton Institute. He returned to the city several years later with a degree and training in the latest printing techniques, but found that the printers’ unions refused to admit African Americans. Undaunted, he earned a law degree, hoping to join the few African American attorneys who’d established themselves in Chicago, only to be rejected by the Illinois Bar because of his dark complexion and southern accent.

Abbott launched the Defender on a minuscule budget, skipping meals to make sure he could pay his printer, and composing each weekly issue on his landlady’s kitchen table. Previous African American–owned newspapers had depended on philanthropy or organizational support, but Abbott had a vision to create a nationwide African American news outlet, one that would be supported by the masses. To achieve this meant reaching into the South. Chicago’s African American population at that time was still comparatively small, just over 44,000 in 1910, while better than 90 percent of the 9.8 million African Americans lived below the old Mason-Dixon Line.

To reach this vast potential readership, Abbott used the journalism techniques pioneered by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer: large headlines, graphics, and separate sections for news, features, sports, and editorials. His paper filled a critical gap in coverage. White-owned newspapers largely ignored African Americans. And though there were many African American–owned newspapers in Louisiana and throughout the South, in this era of legalized segregation and discrimination, southern Black publishers had to be wary of the ever-present threat of violence, while the Defender could print unflinching coverage of the atrocities perpetrated to maintain Jim Crow from the relative safety of Chicago.

“Governor Hall to Probe Caddo Parish Lynching” read the second headline of the January 2, 1915, edition of the Defender, referring to an investigation launched into public murders of African Americans in and around Shreveport. “Five Afro Americans were lynched by mobs within 10 days, three having been ‘strung up’ on a single day,” wrote the newspaper’s anonymous special correspondent. Quoting the statement from Louisiana’s then-Governor Luther E. Hall as well as an editorial in the Baton Rouge–based State Times, a white-owned newspaper, the article counted eight such killings in the previous year and at least fifteen in recent years, adding, “If on the square and not the farce of investigations in other southern states, the entire country welcomes the step.”

When the state’s inquiry indeed proved to be as cursory as its predecessors, however, the Defender was there to hold Governor Hall accountable. An editorial in May titled “The Shreveport Farce” observed that the entire criminal justice system in the state had been corrupted by the impunity demonstrated by Louisiana’s authorities in this case and many others. More often than not, hundreds of people were involved in these public murders, including many police officers, and even in those rare circumstances when someone was indicted, the all-white juries were sure to acquit.

“The investigators accomplished just what they were expected to accomplish—NOTHING,” the editorial stated. “Caddo Parish and the state of Louisiana stand doubly disgraced; first, because of the brutal lynchings, and second, because the cowardly murderers have gone unpunished.”

In March of that year, the Defender published a special report under the headline “Driven from a Louisiana Court,” which added personal detail to the harrowing restrictions placed on African Americans. Adolphus Griffin, a Kansas-based newspaper manager and politician, visited his family in Shreveport and was “disgusted” after being barred from a public courthouse, told by authorities there that African Americans were only allowed inside as prisoners or witnesses. Among the other outrages, Griffin described filthy segregated waiting rooms in train stations, curt treatment from officials, and white mail carriers who simply refused to deliver to many African American neighborhoods.

“This was his first trip to his home in 27 years, and he says things have undergone a radical change since that time,” the article states. “He says that with a few exceptions the Afro-American people are treated like animals—in fact, they are not treated as well as animals.”

Bold headlines, fearless news coverage, and blistering editorials were only part of Abbott’s strategy to realize his vision for the Defender, however. Abbott partnered with, among others, the Pullman porters, the famed valets of the railways, who traveled the country and had expansive networks of contacts. The porters sold subscriptions to the Defender, and encouraged local correspondents to submit news from these widespread cities, towns, and villages, which Abbott published to attract more readers.

Typical of these columns from all across the country were the missives from correspondent L. A. Jackson in Monroe, Louisiana, who kept the Defender’s readers informed about “all the brisk and newsy items of this thriving city.”

Jackson reported on funerals, sports matches, and church gatherings in a lively vernacular style that chronicled the quotidian details of the lives of Monroe’s residents: “Mr. George Lee died in this city on May 23, 1915, after an illness of several months. His remains were laid to rest by the society of his choice in the Monroe cemetery. Emily Howard is yet on the sick list. Mrs. L. N. Wood has been sick for the past week, but is now convalescing. Mrs. V. V. Hauk of this city will spend several weeks sightseeing through Illinois and Kentucky . . . ”

That year, the Defender also covered events at African American institutions elsewhere in Louisiana, including Leland University, founded in New Orleans in 1870, and a visit to the state by Booker T. Washington, Black America’s preeminent spokesperson at that moment, with a popular message of self-reliance. African Americans were all but blocked from voting, let alone running for public office, and even the Republican Party, which had formerly welcomed them, was now imposing a “Lily White” policy to expel them. The Defender covered the few brave enough to try to participate in Louisiana’s GOP, chronicling their ill-fated efforts to win recognition at various party gatherings.

This was the dawn of the Great Migration, when the numbers of African Americans coming north were still low, and Abbott did not initially support a mass departure. He had suffered dire poverty as a result of northern discrimination himself, and did not see the point of coming to Chicago or other destinations when there was no chance to secure a decent job. But this situation was beginning to change as a result of the First World War then raging overseas. While the European empires battled each other in the trenches, the demand for American products grew at a time when the flow of immigrants to the United States dried up, leaving the factories and slaughterhouses increasingly desperate for a new source of labor. Employers and labor unions in northern cities dropped their restrictions against African Americans. Still the Defender’s editorial page remained ambivalent toward evacuation; the war had opened more jobs to African Americans in the South as well, after all.

Abbott only changed his mind in the summer of 1916 after he saw how mass migration could become a political weapon to undermine the Jim Crow system where it was most vulnerable: its economy. In August of that year, the Defender reported that all of the African American stevedores and other dock workers in Jacksonville, Florida, had left en masse when they were recruited by a Pennsylvania-based railroad company. Without these skilled workers, Jacksonville’s port effectively stopped functioning. The city’s panicked city council passed a law to block northern recruiters, and Jacksonville’s white-owned newspapers decried the departure of African Americans, having suddenly, if belatedly, realized that they were a crucial labor force.

In the following weeks and months, the Defender gleefully reported on the large numbers leaving the South, with one headline declaring it “The Exodus,” while the editorial pages were filled with exhortations, poems, and cartoons encouraging the migration, describing it as a “Second Emancipation.”

“Every Black man for the sake of his wife and daughters especially should leave even at financial sacrifice,” stated an editorial that fall headlined “Farewell, Dixie-Land.”

“We know full well that would mean a depopulation of that section and if it were possible, we would glory in its accomplishment.”

The effects of the migration soon showed up in the local news columns from Louisiana. L. A. Jackson had stopped writing his dispatches from Monroe by the beginning of 1917, but Louisiana news now took up a prominent section of a center page alongside similar articles from other states. The March 31 edition contained reports from New Orleans, Baton Rouge, New Iberia, Lake Charles, Hammond, and Alexandria, with this sentence from a visiting correspondent: “G Fontnette has returned from New Orleans and reports that hundreds of the Race are leaving for the north.”

In the Defender’s May 5 edition, the Louisiana news contained this selection from the New Orleans report: “Sunday afternoon, April 22, the Rev. J. W. Willard, pastor of First African Baptist Church, preached one of his strongest sermons and announced the opening of his revival meeting, which continued during the past week—Baseball has topped the sporting program in New Orleans in the past two or three weeks—Mr. Ike Stewart has been sick at his home, 2722 Second Street—Ms. Annette Washington left Monday for the Windy City, where she will make her home. She will live with her niece, Mrs. Eugene Stacke, 4725 S. Dearborn St.”

And a few paragraphs later, this sentence from the report submitted by the city of Franklin mentioned another departure, this time for the West Coast: “Mrs. Theo LeCall and niece, Mary Louise, after spending some time with her mother, Mrs. Mary Johnson, left Sunday to join Mr. LeCall in Los Angeles, their future home.”

As the migration accelerated, the Defender became a vital two-way communications vehicle, keeping those who had moved abreast of changes at home as it encouraged even more to leave with objective news about plentiful jobs, well-equipped schools, and a robust political culture in Black Chicago. Circulation grew exponentially, from 14,000 at the end of 1915 to more than 200,000 in June 1919, and then surging past 250,000 just three years later, so that the Defender became a staple in the homes of African Americans North and South, read and passed around until it disintegrated. Among its most popular sections was “The Defender Jr.,” edited by a succession of young people who took the moniker of “Bud Billiken.” There had never before been a children’s section in a Black press organ, but within days of the announcement of a Bud Billiken Club in 1921, letters and applications poured into the newsroom from young readers across the country. In addition to the articles written by the youths taking their turn as Bud Billiken, the section listed the names of new club members and printed their letters. For many, it was a badly needed connection with other young people.

“Dear Bud: I was the happiest girl in Scotlandville when I saw my name on the honor roll. As soon as the paper came, I ran and got your page. I looked and what did I see? It was my name! Many Thanks, Bud,” wrote one “Louisiana Billiken” in June 1929, before adding: “Bud, I am so lonesome. Will you please tell some of the Billikens to write to me? I promise to answer all letters.”

By the beginning of the Second World War, the Defender was diminished in terms of circulation and national influence as competitors like the Pittsburgh Courier and the Baltimore-based Afro American chain emulated its techniques and became national organs in their own right. But the Defender remained a watchdog over the abuses of the Jim Crow system, and in Louisiana, collaborated closely with a courageous team of local journalists. The New Orleans Press Club, made up of local reporters and editors as well as correspondents for the national African American newspapers, conducted its own investigations of lynching and police abuses, and then released the results to the Defender, the Courier, and others, hoping the national spotlight would prompt change in their state and throughout the region.

In January 1942, the press club investigated the death of Wilson Morin in Caddo Parish and found numerous witnesses who were willing to testify that officers had dragged the man from one local tavern to another, beating him savagely at each location, before finally leaving him to die in a cell in the county jail. Chastising the local prosecutor for his shoddy examination of the incident, the press club report, as reprinted in the Defender, noted that neither the Shreveport district attorney nor the state attorney general had responded to the evidence they’d gathered nor their offer of testimony: “Please be advised that it is embarrassing to us as to you to have Louisiana as yet listed among the states of this nation that haven’t eradicated barbarianism, but, regretfully, there is no other alternative if our state officials are thus endowed.”

The press club’s role became particularly sensitive in the following months, as US troops—white as well as African American—arrived in the state to prepare for overseas deployment. After a race riot in the city of Alexandria left as many as ten soldiers dead and more injured and arrested, the press club’s investigators, publisher James B. LaFourche and Leon Lewis, methodically interviewed witnesses, including soldiers, local residents, and undertakers, gathering sworn statements, which they offered to military police. But the military refused to protect the witnesses from retribution by local authorities, so the press club locked away the affidavits, wrote news articles about the incident, and released them to the national Black press.

Enoch Waters was just then in town reporting for the Defender on the conditions faced by African American soldiers, and found the situation so tense that he predicted another riot was inevitable. He recounted the details of the investigation by the press club—which he described as “an organization of militant Negro newspapermen”—for the Defender’s national readership, as well as the coordinated efforts of the local NAACP. It was one more step forward in a decades-old journalistic partnership that drew on the indelible bond between Chicago and Louisiana, a collaboration of those who left and those who stayed behind, fueled by their commitment to struggle together for justice and civil rights for all African Americans.

Ethan Michaeli was a copy editor and investigative reporter at the Chicago Daily Defender from 1991 to 1996. His first book, The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), was named as a Notable Book by the New York Times, Washington Post, and Amazon.

This article is part of Split Press: Democracy, Race, and Media in Black and White, a four-part multimedia series exploring the relationship between the media and African American and Afro-Creole experiences of citizenship and civil rights in Louisiana. Part of the Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative, Split Press is a project of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities made possible by a grant from the Federation of State Humanities Councils with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For additional Split Press coverage, stay tuned to 89.9 WWNO New Orleans and 89.3 WRKF Baton Rouge.