Comité des Citoyens

The Comité des Citoyens was an equal rights organization formed in 1891 that played a key role in the events leading up to Plessy v. Ferguson.

Amistad Research Center at Tulane University

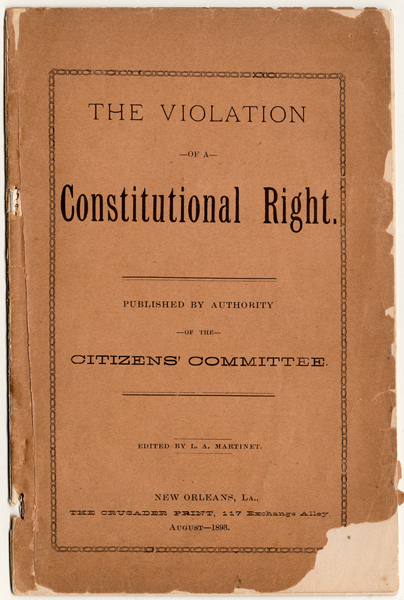

The Violation of a Constitutional Right by the Citizens Committee, 1893.

The Comité des Citoyens, or Citizens Committee, was an equal rights organization formed in September 1891 by a group of French-speaking men of African descent to resist the resurgence of white supremacy in Louisiana, codified by segregation after Reconstruction.

Background

Local and state laws in place before the Civil War restricted people of African descent in many areas of life, particularly freedom of movement, education, and property ownership. People of African descent advocated and agitated to improve these oppressive conditions. Enslaved people initiated revolts for liberation, notably the 1811 German Coast Slave Insurrection, and free people of color mounted petitions, held rallies, marched, and used the court system to secure equal rights.

During Reconstruction (1865–1877), while federal and state governments attempted to undo oppression of formerly enslaved and free people of color, New Orleans newspapers L’Union and La Tribune de la Nouvelle Orléans encouraged their progressive Black readership to fight for equal rights. The ideologies behind these long-standing and varied acts of liberation fed the creation of the Comité des Citoyens.

After the 1866 New Orleans Mechanics’ Institute Massacre, when white supremacists beat and murdered participants and bystanders of a racially integrated constitutional convention, the oppression of African descendants in the South gained national attention. In response, the 1868 Louisiana State Constitution disenfranchised former Confederate rebels and opened access to the vote for some Black Louisianans. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the US Constitution further codified equal rights. As a result, public transportation, education, coffeehouses, entertainment venues, and more became legally integrated. The federal government stationed troops in Louisiana to enforce these new legal protections. However, in 1877 federal troops left Louisiana, abandoning the enforcement of equal rights laws to local officials. White terrorism increased to subdue Black gains, and Black voters became afraid for their lives. The 1879 Louisiana State Constitution ended equal rights for Black citizens.

The Citizens Committee

By 1890 a new state law came into effect creating separate railcars for Black and white people. The “Comité des Citoyens (Citizens’ Committee) for the Annulment of Act No. 111, Commonly Known as the Separate Car Law” organized to test this new law in an attempt to reverse segregation.

The eighteen founders of the Comité were a coalition of post Civil War activists and young advocates, supported by church groups, community members, benevolent associations, Radical Republicans, and others—both French and English speaking throughout the United States. Comité members were successful businessmen, professionals, former soldiers, and others who occupied the wealthier echelons of the Black community. Members were well educated, some having attended law school at Straight College. Most lived in the downtown neighborhoods of New Orleans that were historically populated by free people of color before the Civil War—the Faubourgs Marigny and Tremé and the French Quarter. Some Comité members were descended from this legally privileged and overwhelmingly Catholic group and bore the appearances of their European ancestors. However, all Comité members were committed to equal rights without regard to skin color. Comité members had deep roots in Black social and benevolent organizations that later financially supported the group’s legal test cases.

Comité founders included Louis A. Martinet, a lawyer and the publisher of the Crusader, a Republican newspaper addressing issues that concerned Black people; Myrtil Piron, who had lived in Haiti and was a former president of the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle; and Rodolphe Desdunes, an activist and author who wrote for the Crusader. Haitian sailmaker and Couvent School trustee Arthur Esteves was the Comité’s president. C. C. Antoine, Louisiana’s lieutenant governor from 1873 to 1877, was vice president. Other founding members included Firmin Christophe, G. G. Johnson, Paul Bonseigneur, Laurent Auguste, A. J. Guirenovich, Alcée Labat, L. J. Joubert, Pierre Chevalier, N. E. Mansion, Eugène Luscy, A. B. Kennedy, E. A. Williams, and R. B. Baqué.

The Comité announced its existence in the Crusader on September 5, 1891, and then began fundraising to support a legal challenge to the Separate Car Law’s challenge to equal rights. Albion W. Tourgée, a white New York lawyer, and James C. Walker, a white New Orleans lawyer, joined the Comité’s cause.