Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana

The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana is the largest of four federally recognized tribal governments in Louisiana.

This entry is High School Civics level View Full Entry

The Historic New Orleans Collection

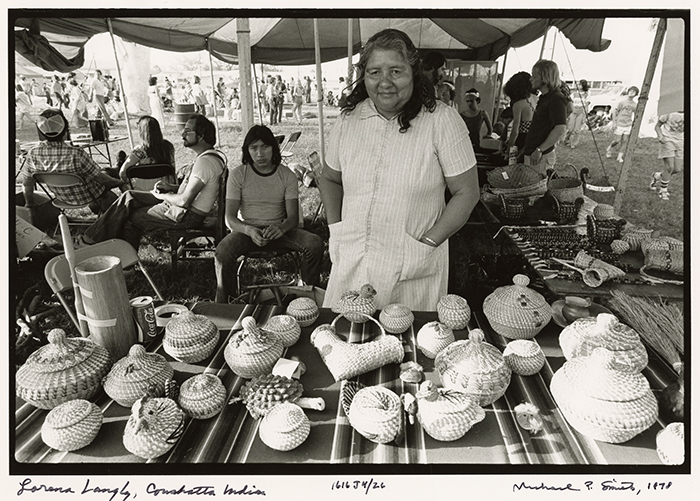

Lorena Langley stands by her craft table at the 1978 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Michael P. Smith, photographer.

Where do the roots of the modern Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana begin?

There are four federally recognized tribal governments in Louisiana, and the Coushatta is one of four. The tribe is the only one comprised entirely of Coushatta Indians (also called Koasati in their native language). It was while living on islands in the Tennessee River that the Coushatta first encountered the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto circa 1500–1542. De Soto visited them because the Coushattas were proficient farmers. As a result of drought and the encroachment of European settlers and rival tribes, the Coushatta moved southward in 1700. In alliance with the Creek Confederacy, they established villages near the junction of the Alabama, Coosa, and Tallapoosa Rivers near present-day Coosada, Alabama. While maintaining their unique identity, culture, and language, the Coushatta grew in social and political standing within the Creek Confederacy by the second half of the eighteenth century.

The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana has consistently maintained its identity and status as a sovereign nation despite repeated attacks on their lands, homes, and culture. Today the tribe has approximately one thousand members and owns more than six thousand acres of land in Louisiana. The tribe also owns and operates a casino resort that opened in 1995 and has since become one of Louisiana’s largest employers.

Naaksaamit Stamahilkato (How We Began)

Coushatta and other southeastern tribes organized their social and political worlds into hierarchical, centralized societies controlled by hereditary chiefs or elite groups before European contact. Coushatta villages were closely affiliated with the large and powerful Muskogean-speaking Coosa paramount chiefdom (a large, regional, multitiered political organization), which controlled territory from eastern Tennessee to east-central Alabama, and traded with other tribes throughout what is now the United States.

Coushattas built large villages along riverbanks and on islands. They were farmers who cultivated corn, hunted game animals, and gathered wild plants and fruits to supplement their diet. Archaeological evidence indicates that Coushatta villages consisted of dwellings that surrounded an open-air ceremonial court, public buildings, and other community structures on top of earthen mounds. The discovery of recent archaeological evidence has confirmed tribal oral histories of Coushatta history prior to European contact by clarifying the relationship between the tribe and the large ceremonial mound sites found in the southeast, such as Moundville, Alabama.

What was the effect of colonization on Coushattas?

Europeans and rival tribal nations continued to encroach on Coushatta homelands in Tennessee. Having relocated to Alabama around 1700, the tribe established villages and formed alliances with tribes in the Muskogean-speaking Creek Confederacy. In the eighteenth century the Coushatta used diplomacy to strengthen alliances and strategic relationships with other tribes and colonial governments. Although the tribe established friendships and marriage alliances with the French at Fort Toulouse in present-day Alabama, it remained neutral during conflicts such as the French and Indian War (1754–1763). In the aftermath of the British victory, the French ceded Louisiana to Spain and abandoned their colonies on the mainland of North America. Many French people emigrated west, crossing the Mississippi River to live in Spanish Louisiana. A group of Coushattas also joined them.

Despite the Creek Confederacy’s military and political strength, colonial pressures and continued encroachment led many more Coushattas to leave their Alabama villages. In 1797 approximately half of the remaining Coushattas migrated west to Spanish Louisiana led by the influential leader Mikko (Chief) Red Shoes over a decade before the start of the Creek Wars (1813–1814). Coushattas credit the wisdom and diplomacy of early leaders such as Mikko Red Shoes and Pahi Mikko (Grass Chief) for bringing the tribe through numerous perils, including war, forced removals, and assimilation campaigns. The wisdom and diplomacy of Mikko Red Shoes was appreciated by Spanish officials, who accepted his offer to serve as an interpreter and help negotiate a lasting peace between other tribes such as the Caddo and Choctaw. Due to the actions of Mikko Red Shoes, Spanish officials recommended that Coushattas receive assistance to settle in Spanish colonial territory during a time when other tribes were either denied admission or removed.

As the Coushattas moved within the Neutral Strip between Louisiana and Texas during the nineteenth century, their economy continued to be sustained by their agricultural proficiency, hunting skills, and basket trade. They settled along the Red River and then the Sabine, Trinity, and Calcasieu Rivers before finally reaching Bayou Blue in the 1880s. Throughout their journey, Coushattas maintained frequent contact with their extended families in Alabama, Texas, and Oklahoma by traveling the Coushatta and Alabama Traces—open paths that connected Alibamo (Alabama) and Coushatta villages. As in the past, alliances and intermarriages between the groups continued.

What is life like for the members of the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana today?

In the 1880s Coushattas used the Homestead Act of 1862, which allowed citizens to purchase up to one hundred sixty acres of public land for a small registration fee, to build homes and establish their own community at Bayou Blue, three miles north of Elton, Louisiana, where the tribe still lives today. The twentieth century brought new challenges to Coushatta tribal leaders, who were desperate to improve living conditions within the community despite receiving no funding or support from the federal government due the government’s unilateral decision to terminate the Coushatta’s status as a federally recognized tribe.

In the first half of the twentieth century, tribal leaders succeeded in getting limited federal funding for health care and education by using their traditional diplomacy and alliance-building skills. However, this relief was short lived, since services to the Coushatta were abruptly terminated in 1953 without congressional approval or legislation. In 1965, in the midst of abject poverty, community members came together to create the Coushatta Indians of Allen Parish and create a trading post to sell their rivercane and pine-needle baskets. To restore health-care services for tribal members, tribal leaders continually built political alliances and petitioned the federal government’s Indian Health Service. As a result of these efforts, the Louisiana Legislature recognized the Coushatta at the state level in 1972. On June 27, 1973, the US Department of the Interior formally re-recognized the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana. Ernest Sickey, who led the re-recognition efforts, became the first tribal chairman of the officially re-recognized tribe.

The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana is governed by a five-person elected tribal council headed by a tribal chairman. Every council member serves a four-year term; terms are staggered with tribal elections every two years. Coushattas maintain a matrilineal clan system that regulates marriage patterns and kinship relationships and dates back centuries. Membership in a clan is also a mechanism for ensuring shared governance within a tribal community. Seven Coushatta clans exist, including Fiito (Turkey), Icho (Deer), Kawaknasi (Bobcat), Kowi (Panther), Nokko (Beaver), and Takchaiha (Daddy Longlegs). Among the other federally recognized tribes with Coushatta members are the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, which has a reservation near Livingston, Texas, the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town in Wetumpka, Oklahoma, and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Okmulgee, Oklahoma.

The Coushatta are the only tribe in Louisiana to retain their native language as a first language, although Koasati usage continues to decline. As a result of a National Science Foundation Documenting Endangered Languages grant, the Coushatta Tribe began a comprehensive Koasati language documentation and revitalization project in 2007, with the assistance of McNeese State University and the College of William and Mary. This effort has resulted in the digitization of more than sixteen thousand pages of Koasati manuscripts, the creation of a multimedia dictionary and tribal archives, as well as the development of numerous Koasati teaching resources. Coushattas have launched several initiatives to strengthen spoken Koasati within the tribal community in recent years, including summer heritage camps, immersion language classes, an immersion pre-school, and “Language Nests,” where parents and infants are immersed to naturally produce Koasati first-language speakers.

The Coushatta continue to be known for their basketry tradition, both in the form of woven rivercane baskets and coiled longleaf pine-needle baskets. In particular, the Coushatta are renowned for their longleaf pine-needle effigy baskets, which are woven in a variety of shapes and sizes and are valued by museums and collectors throughout the United States. Through classes and workshops, the tribe actively promotes the continuation of its famed basketry traditions. Some younger tribal members have become proficient weavers, and some promote the art form through online marketing and sales.

As a result of its federal recognition, the tribe has been able to pursue many more avenues for economic self-sufficiency, including the Coushatta Casino Resort, which opened in 1995 in Kinder, Louisiana, and which is now one of the state’s largest employers. Smaller tribal enterprises include health, educational, social, and cultural programs that are influential in southwest Louisiana. Today the Coushatta Tribe owns more than five thousand acres of land in Allen Parish and more than one thousand acres in nearby parishes. This land is used by the tribe for housing, crawfish and rice farming, the development of non-gaming businesses, and the construction of tribal government buildings, such as fire, police, and health departments. Hundreds of years of uncertainty and migration have culminated in self-sufficiency for the Coushatta Tribe in the twenty-first century.