Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (MR-GO)

Conceived of as an emergency outlet for the lower Mississippi River that would provide a more direct route to New Orleans, MR-GO was controversial even before its 1963 opening.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

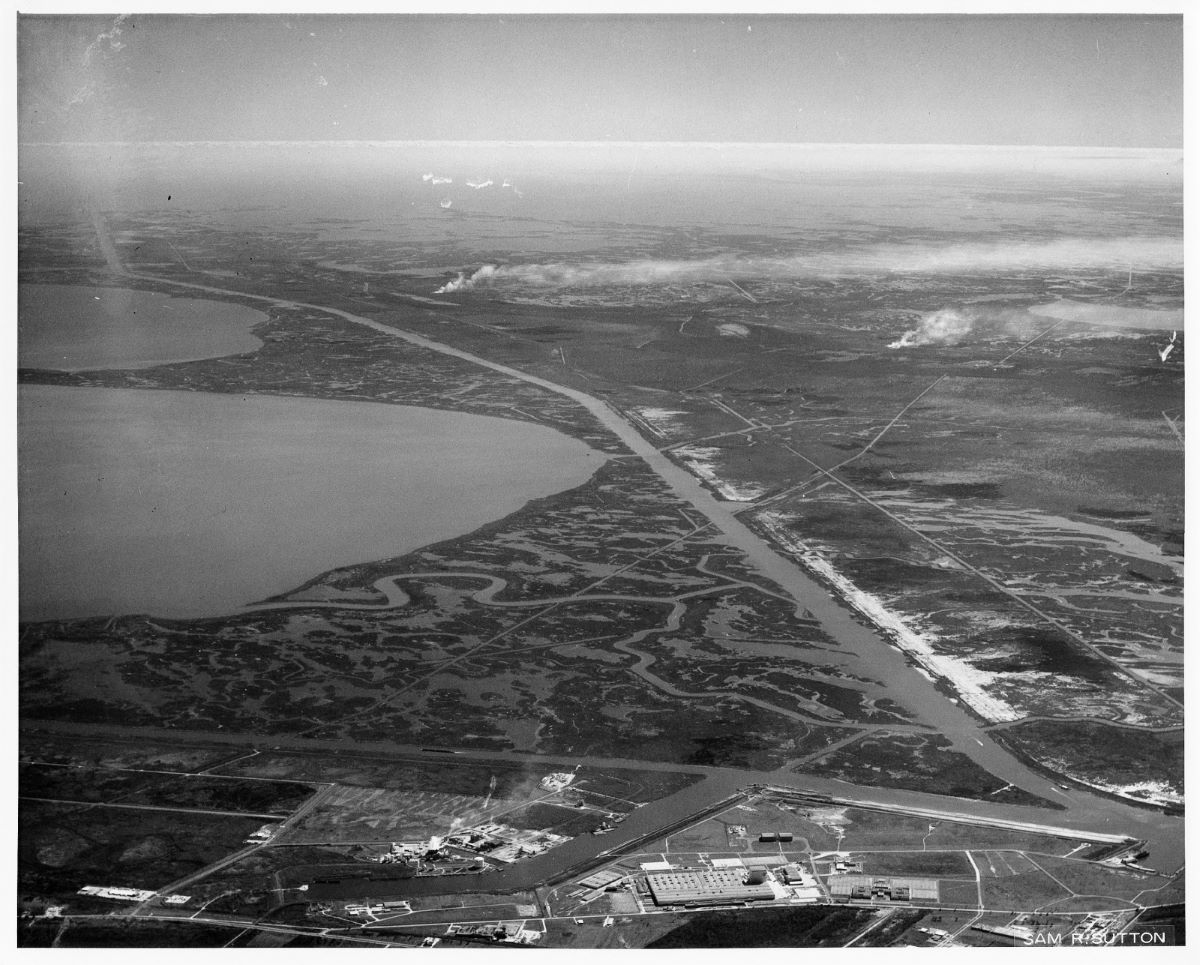

MR-GO from NASA to the Chandeleur Sound. Photo by Sam Sutton.

The Mississippi-River Gulf Outlet, or MR-GO, was conceived as an emergency outlet for ships to reach inland ports along the Mississippi River in the event of enemy sabotage during World War II and as a more efficient route for ocean-going cargo ships to reach the Port of New Orleans. Promoted by local leaders to reinforce the city’s position as a leading harbor, it became embroiled in controversy even before it opened to shipping in 1963. Over the next few decades, low usage, erosion of its banks, and salt-water intrusion of surrounding marshes prompted criticism for both its financial failure and environmental damage. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 drove storm surge up the canal and contributed to extensive damage in the city and motivated its closure in 2006.

Seeking a Tidewater Canal

The earliest international trade in New Orleans relied on direct maritime access to the city via Lake Pontchartrain and Bayou St. John. With the advent of steam-powered navigation, inland and maritime trade consolidated along the Mississippi River waterfront. Nonetheless, the long route from the Gulf of Mexico, against the river’s current, stimulated grand notions of a waterborne shortcut to the city. In the 1940s local officials asked the federal government to build a more direct shipping route. Initially, the US Army Corps of Engineers, which maintained the main channel of the Mississippi River, expressed little support for an alternate route. Nonetheless, during World War II, local port advocates argued that a canal could serve another, pressing need—an emergency outlet should adversaries block navigation on the Mississippi River. In the Cold War era of the 1950s, this national security argument prevailed. Following the completion of a favorable benefit-cost analysis, work began on MR-GO in 1958, despite skepticism from scientists and fishermen who were concerned about impacts to commercial fishing. Shortly after work began, NASA acquired property along the canal, where it has assembled rockets and other equipment for the space program that could be shipped on the Intracoastal Canal to Florida.

Creating a Canal and Controversy

Criticism by those concerned with its environmental impacts began even as work on MR-GO was underway. Conservation officials pointed out that the canal would have negative impacts on commercially significant shrimp and oyster populations and the fisheries they supported. They estimated losses would reach $6 million a year or slightly more than the Corps’s estimate of $5.8 million a year in benefits.

Construction proceeded, however, and in 1963 crews completed dredging the seventy-six-mile-long, thirty-six-feet-deep main channel that traversed St. Bernard and Orleans Parishes. At its surface, the completed canal was 635 feet wide. The canal merged with the Intracoastal Canal, offering a connection to the river via the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Locks.

Even before its opening, saltwater intrusion damage became obvious in the adjacent wetlands. The channel permitted salt water from the Gulf into freshwater swamps and marshes, killing salt-intolerant cypress trees and freshwater marsh grasses. Local ecosystems were thoroughly altered. Freshwater-species habitats were greatly restricted, and saltwater habitat crept closer to the coast. These changes disrupted but did not destroy shrimping and oyster cultivation. Estimates complied in the early 2000s reveal that MR-GO was responsible for the destruction of somewhere between 23,000 to 65,000 acres of wetlands. As the marsh grasses died, their root systems that had held the wetland soils together became disentangled, allowing increased erosion. The wake of ships passing through the canal accelerated this erosion. The loss of wetlands and increased erosion resulted in the canal widening from 635 feet in 1963 to 2,000 feet in 2005.

Advocates for MR-GO had argued that it would be an economic benefit to New Orleans and shipping throughout the Mississippi River valley. By providing a shorter route from the Gulf of Mexico, it would reduce transit time for ocean-going cargo, and it would stimulate development of real estate along its banks in St. Bernard Parish and along the Inner Harbor Navigational, or Industrial, Canal that provided a link to the Mississippi River. Between 1963 and 1978, tonnage shipped via MR-GO increased dramatically, maxing out at 9.4 million short freight tons (SFT). Nonetheless, there was a precipitous drop from the peak until 1984, followed by a noteworthy recovery in 1985. After that rebound, MR-GO’s cargo totals fell steadily, hitting a low point of just over 1 million SFT in 2004. That year there were only a dozen round trips by ships that required a 36-foot channel. Maintenance dredging costs in 2004 were $19.1 million, or $1.5 million per round trip.

MR-GO never delivered the results its boosters promised. Despite the huge investment, it failed to lure shipping away from the Mississippi River. On average, only about one to four ships used the canal daily, and it handled about 3 percent of the New Orleans port’s freight tonnage. The federal government’s significant investment did not stimulate the private-sector development envisioned by the canal’s promoters. The absence of port facilities along the canal and direct connection to river shipping deterred its use. And by 2000, the cost of dredging the canal to maintain a navigable channel commonly exceeded the benefits of commerce, undermining its economic viability.

Closing MR-GO

When Hurricane Betsy made landfall near Grand Isle, Louisiana, on September 9, 1965, it drove a surge up the canal that contributed to flooding in several New Orleans neighborhoods. This episode earned MR-GO the nickname “hurricane superhighway” and fostered skepticism of the US Army Corps of Engineers’ projects in St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes, such as the Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion and the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion projects.

Hurricane Katrina delivered the final blow to the canal in 2005. Levees paralleling MR-GO and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway converged east of New Orleans, creating a funnel where hurricane winds drove storm surge and waves into the funnel’s spout pointing towards the Industrial Canal. The constriction amplified the height of the hurricane-driven surge, caused overtopping of the levees, and drove massive amounts of water into the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal, overtopping the flood wall in New Orleans’s Lower 9th Ward. A torrent of water poured over the cement barrier and eroded the soil at its base, resulting in two breaches that released a massive wall of water that bulldozed through the adjacent neighborhood. It demolished hundreds of homes and killed scores of unsuspecting residents. Extensive flooding also occurred throughout St. Bernard Parish when the surge overtopped the levees designed to protect the parish residents and property.

Following Hurricane Katrina, the US Army Corps of Engineers conducted a study on decommissioning MR-GO. Their 2008 report recommended de-authorization of the canal, construction of a closure structure, and the development of a plan for ecological restoration. By 2009, a stone structure spanned the channel, ending its use for large cargo ships and permitting restoration to begin. With investments from the US Army Corps of Engineers and the State of Louisiana and actions by several nongovernmental organizations, significant progress has been made with restoration of freshwater conditions in the wetlands and reestablishing oyster populations.