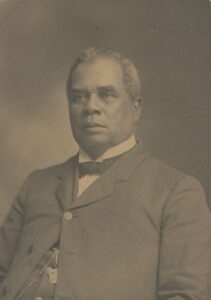

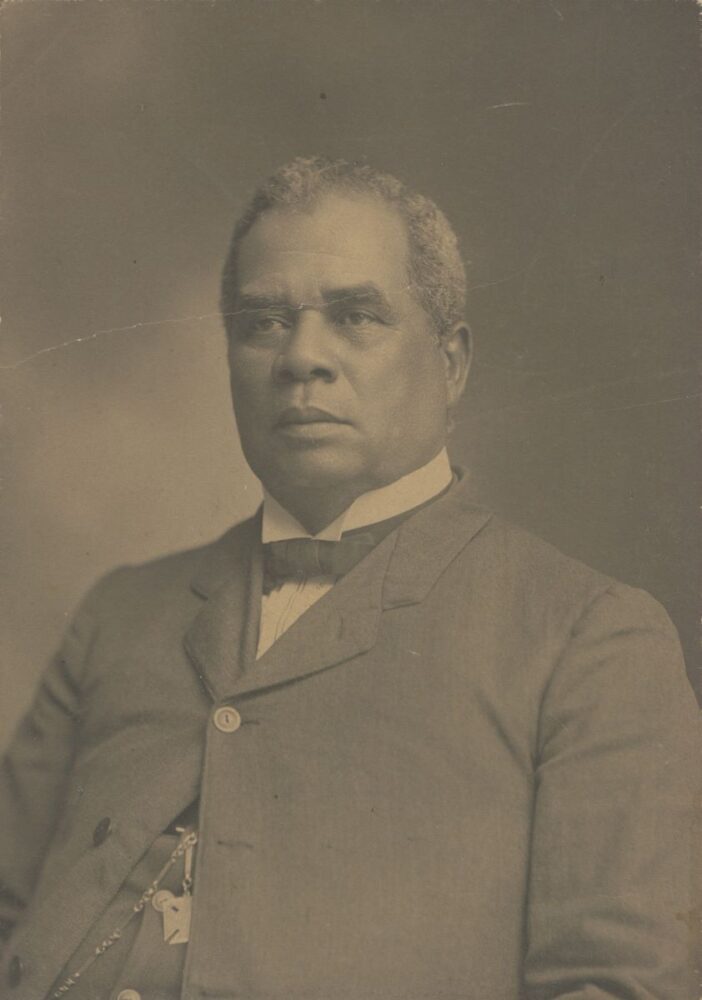

Pierre Caliste Landry

Born enslaved in Ascension Parish, Pierre Caliste Landry became the first Black mayor in the United States in 1868.

Amistad Research Center

Pierre Caliste Landry.

Pierre Caliste Landry was a Black politician, clergyman, and educator during Reconstruction and after. In 1868 he was elected mayor of Donaldsonville, becoming the first Black mayor in the United States. Like other Black politicians in the post–Civil War South, Landry was a member of the Republican Party. At the time the party was popular among formerly enslaved Black people, which helped Landry secure public appointments and victories in local and state elections. During the 1870s he led the Ascension Parish Police Jury, worked as a state tax collector and federal postmaster, and won election to Louisiana’s House of Representatives and Senate. He served in the state legislature between 1872 and 1884.

Like most of his constituents, Landry was born enslaved on a sugar plantation in Ascension Parish. Landry lived most of his life in Ascension Parish, though he appears to have been in New Orleans during the Civil War and near the end of his life. He married Amanda Grigsby in 1867 and, after she died, Florence Simpkins in 1886. He had fourteen children, twelve with Grigsby and two with Simpkins.

Landry had unique educational and entrepreneurial opportunities that prepared him for financial and political success after his emancipation. From an early age he was supported by Donaldsonville’s small community of free people of color and their white acquaintances, likely with his enslavers’ consent. Pierre Damas Bouziac and Zaides Bouziac, both free people of color, and a white female teacher, surnamed Reno, educated the young Landry. He also learned pastry making from a Madame Dumond. When Landry’s enslaver, François Marie Prevost, died in 1854, Landry was auctioned to Marius St. Colombe Bringier. Landry used his education, confectionary skills, and trustworthiness to ingratiate himself with Bringier. The enslaver made Landry his butler and put the young man in charge of his fellow enslaved domestic servants. Bringier also delegated to Landry some of the plantation’s commercial activities, such as selling wares to passing steamboats. While such arrangements were exceptional, they were not unheard of, especially on large plantations or where enslavers spent most of their time away in nearby towns and cities. By the Civil War Landry had learned the basics of operating a mercantile business.

Emancipated during the Civil War, Landry entered freedom as an educated man with business acumen. A store he opened in Donaldsonville in the 1860s was successful, and he became part of the small but growing Black middle class. Like many post–Civil War Black politicians, Landry’s first leadership positions were in the Black church. In 1862 he converted from Catholicism to Methodism and, as a lay leader, helped start St. Peter Methodist Episcopal Church in Donaldsonville.

Landry was elected to the state’s House of Representatives in 1872 but served most of the 1870s in the Senate beginning in 1875. He returned to the House in 1880 and served four years.

Landry served in the state legislature during the 1870s and retained his position in the legislature into the mid-1880s, when members of the antebellum establishment, former Confederates, and a new generation of white supremacists began returning to political power after the end of Reconstruction in 1877. In his unpublished autobiography Landry detailed how he allied with former Confederates. Black Republicans in the late 1870s and 1880s sometimes engaged in this type of “fusionism” with white Democrats to maintain a seat at the table in an era marked by political and racial violence and reduced Black political power. Landry’s tactics worked for a time. He was just one of seven Black delegates to the state constitutional convention in 1879 (half the delegates to the 1868 constitutional convention were Black). A white Democrat replaced Landry after the 1884 election for the House of Representatives.

After Landry’s political career ended, he returned to a career in the Methodist Church as a clergyman and educator. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, he pastored churches and led ecclesiastical districts. Between 1900 and 1905 Landry served as dean of Gilbert Academy, a Black college preparatory school in New Orleans affiliated with his church and New Orleans University (now Dillard University), which he helped found in 1868. He also served on the Board of Trustees for Flint Medical College. Before his death in Algiers in 1921, Landry joined the Missionary Baptist Church, potentially because he was accused of stealing money from a Methodist home for the elderly—a charge he refuted in his autobiography. State and local leaders attended and spoke at his funeral, including former Louisiana governor Henry C. Warmouth. Landry is interred in Carrollton Cemetery No. 1 in New Orleans.