Louisiana Constitutions

Louisiana has had ten state constitutions since 1812, with the current governing document dating to 1974.

National Archives and Records Administration

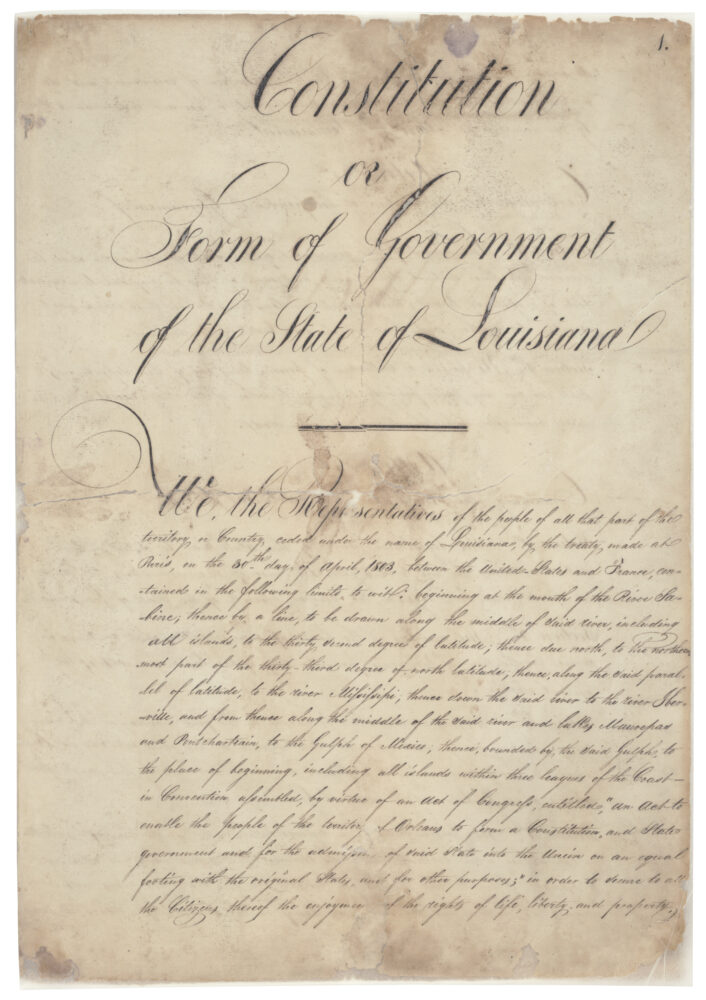

The Constitution of the State of Louisiana, January 22, 1812.

Written constitutions are organic foundational law in the American scheme of government. The US Constitution sets the boundaries of federal authority. State constitutions are similarly designed. They have been written and rewritten periodically ever since the states became states. Louisiana has had ten constitutions, and their words, rationale, advocates, and opponents delineated the Bayou State at exact moments in time. Collectively, all contributed significantly to making the state what it once was and now is. They were elemental to Louisianans’ quest for organic law between 1812 and 1974.

Constitution of 1812

In February 1811 President James Madison initialed an act of congress that authorized Louisiana to write a constitution establishing statehood. After the territorial assembly passed the necessary enabling law, Louisiana Governor William C. C. Claiborne proclaimed an election for a constitutional convention that sat in New Orleans. Forty-five delegates were unevenly apportioned among the existing twelve civil parishes; Orleans Parish had the most, Ouachita Parish the least. Any adult free, taxpaying, white, male, American citizen who had resided in the territory a year or more could vote and stand as a candidate.

Twenty-six delegates were of French origin. Some descended from families with deep roots in the colonial past; some were native-born Frenchmen. Men from Virginia, New York, Massachusetts, and Kentucky numbered among the Americans. There were also Spaniards, a Swiss, a German, and an Irishman who was not yet a citizen. Irrespective of their origins, the delegates belonged to a small clique of territorial legislators, judges, attorneys, planters, and wealthy white men who presumed as natural their right to rule. Several prominent figures, including Edward Livingston, Louis Moreau Lislet, and François-Xavier Martin were absent. They had run, but Governor Claiborne had engineered their defeats at the polls.

The convention was supposed to begin early in November 1811, but bad weather and an outbreak of yellow fever forced a delay. When conditions improved, the delegates convened, and by January 1812, they were finished. Their constitution established New Orleans as the seat of government. It had a preamble that preceded the organization of government into three equal branches—legislative, executive, and judicial, each with defined powers. Articles created officers of state and described the manner of their selection and how they could be impeached. Other articles apportioned representation, described who could vote, and laid out a schedule for the transition from territorial to state rule.

Official copies in hand, one English, one French, convention members Elegius Fromentin and Alan B. Magruder went to Washington, DC, and delivered them to President Madison and Congress. The constitution was approved, and on April 30, 1812, Louisiana became the eighteenth state to join the Union.

The Constitution of 1812 resembled other state constitutions of the day. It was a brief specification of organizing principles and no more. By virtue of being first, it was the foundation of institutions that still exist. It furthered the mixing of Anglo-American and European precepts of law into a frame of self-governance that makes Louisiana a distinctive legal order, but it also contained the seeds of its destruction.

Constitution of 1845

Stretching the constitution to cover the realities of a state that no longer resembled the Louisiana of 1812 grew ever more difficult as the years passed. It was criticized as archaic, undemocratic, and impossible to modernize. The demands for constitutional reform grew so loud by the mid-1840s that they were politically difficult to ignore. In 1844 the general assembly enacted a call for a convention and authorized it to revise or replace the constitution.

As a concession to delegates from rural areas, the convention assembled in August in the East Feliciana Parish town of Jackson. An agreement to recess until January 1845 and to reconvene in New Orleans, ended a short, contentious session. Issues that divided the delegates in August were no less vexing after the convention reassembled in January. Broadening the right to vote, apportioning representation, diminishing the political weight of New Orleans, protecting slavery, and reforming the judiciary were among the most divisive. They and the less controversial issues, such as qualifications for holding office, inspired ferocious debates that dragged into May 1845 before the delegates compromised just enough to agree on a new constitution.

Unlike in 1812, the new constitution was put to a popular vote. Governor Alexandre Mouton called a special election for the fall. In the run-up to that election, a scandal involving Louisiana Supreme Court Judge Rice Garland intensified the voters’ scorn for the old constitution and helped to ratify the new one by a margin of twelve to one.

Viewed for the first time, a voter would have immediately been struck by the greater length and details of the new constitution. The franchise, or right to vote, was extended to all free adult white males who resided in the state for twelve months and in the home parish for six months. Property qualifications for those running for governor were gone, and there were new executive officers. Seats in the general assembly were apportioned to favor the rural parishes over New Orleans, and the city lost its place as the seat of government. Reforms to the Supreme Court of Louisiana included term limits for its members who were designated chief and associate justices and who were empowered to take criminal appeals. Voters would have noticed certain radical features—namely, restrictions on the ability of the general assembly to legislate and the abolition of banks and corporations. One article required public schools to teach white males so-called “southern ways,” in an effort to maintain support for slavery and white supremacy.

Although the Constitution of 1845 improved on its ancestor, it contained elements that were incompatible with antebellum Louisiana. Consequently, it lasted for only six years, five months, and six days before a third convention ditched it.

Constitution of 1852

No sooner had the new constitution gone into effect than its inadequate elements surfaced. Its provision for an unelected four-member supreme court proved problematic. Too often the justices could not decide appeals. Their indecision led to confusion, unsettled law, and frequent accusations of incompetence. Biennial sixty-day sessions of the general assembly hampered the business of governing. Prohibitions against banking and corporations, aimed at New Orleans, dried up capital and threatened economic strangulation across the state. These and other incompatibilities raised the prospect of Louisianans living with an impractical fundamental law or reforming it.

Reform seemed almost impossible. Although the amending procedure was less torturous than the provision in the first constitution, it was difficult, nonetheless. Still, the greater obstacle was the political reluctance to tackle amendments or to hold another constitutional convention. Efforts to convene one flagged until 1852, when the general assembly called a referendum on the question. After a favorable vote, delegates were elected, the convention met, and the third constitution was narrowly ratified by less than thirty-two hundred votes.

There were 153 articles in the Constitution of 1852, which was the same number as were in the old document. Two-thirds of the articles migrated from the discarded constitution with little or no revision. The remaining third represented substantial modifications. Annual legislative sessions were restored. Gone were the prohibitions of banks and corporations. Changed was the basis of apportioning seats in the general assembly. Instead of counting only qualified voters, representation was based on the total population in each parish, and that gave more clout to large slaveholders in parishes with small numbers of white people. Qualifications for holding office were eased. The judiciary was made elective, and a fifth member was added to the supreme court bench. An internal improvements article was meant to keep Louisiana economically viable with other regions in the nation. The revised amendment article eased future constitutional reforms.

Despite its narrow approval and its shortcomings, the new constitution ended up in a different place than its predecessors. After 1852 the taste for constitutional revision diminished as many white Louisianans sharpened their appetites for defending slavery. Secession became the watchword and alluded to protecting slavery and white supremacy in coded terms such as “southern rights” and “the southern way of life” and staving off “northern aggression.”

In 1861 secessionists pulled Louisiana out of the Union and joined the Confederacy. The rebels purged the Constitution of 1852 of its references to the United States and adopted it without a popular vote. Subsequently, it became a tie between past and future revisions of Louisiana’s organic law.

Constitution of 1864

The era from the beginning of Reconstruction to the end of the nineteenth century was the most violent and corrupt time in the state’s history. Efforts at restoring Louisiana to the Union as an inclusive, equitable, more gentle society were repeatedly stifled by white supremacists. Their successes meant the return of white home rule by the Democratic Party, the coming of Jim Crow, and the ruthless exploitation of most Louisianans.

In 1864 General Nathaniel Banks summoned a convention to write a constitution for the parishes under Federal control. Meeting in Liberty Hall (formerly the Lyceum, where the rebels had voted to secede), the convention lasted four months. The delegates were notable as much for their contentiousness, their absenteeism, and their penchant for bribery and extravagances as they were remarkable for the constitution they produced. Aside from replicating provisions in the Constitution of 1852, the new document broke with the past. It abolished slavery without compensation for the enslavers and established a minimum wage and a nine-hour workday. State taxes would fund segregated public education, and it provided for a lottery to fund state government. The abolition of slavery notwithstanding, the convention refused to grant all Black Louisianans full social or political equality. Nevertheless, the constitution authorized the general assembly to grant the franchise to Black men who fought for the Union, owned property, or were literate.

The Constitution of 1864 was vehemently condemned by Black Louisianans. It angered the Republicans in Congress who refused to recognize it. President Andrew Johnson embraced it and granted blanket pardons to former rebels. Ex-Confederates quickly dominated the general assembly and laid ever greater restrictions on the freed people in the Black Codes. Pressed hard by Black and white Republicans, a reluctant Governor Michael Hahn recalled the constitutional convention in July 1866. When the conventioneers and their supporters gathered peaceably at the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans, they were attacked by a band of white policemen and other white people. Most of the dead and injured were Black Louisianans. The assault was a harbinger of white Democrats’ unremitting use of violence to regain power and to suppress the rights of Black people. It also loosed events that brought about the fifth iteration of Louisiana’s organic law.

Congressional Republicans reacted swiftly to the Mechanics’ Institute Massacre. Wresting control from President Johnson, they passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867 that put General Philip H. Sheridan in command of Louisiana. The statute authorized Sheridan to register all adult Black and white men who could prove they had not willingly supported the Confederacy to vote. That requirement enfranchised Black men. It effectively disenfranchised most white men, and it encouraged what was the most revolutionary feature of constitution-making in Louisiana: the prominent role of Black Louisianans in drafting the Constitution of 1868. Half of the delegates were Black, and they joined with like-minded white people to write the document.

This constitution departed from those that came before. It incorporated a bill of rights, a first. It also eliminated the Black Codes of 1865, public whippings, and imprisonment for debt, and lowered the number of capital crimes. Articles accorded women property rights and required care for the indigent at public expense. Several articles called for free, integrated public schools, including what became Southern University. Others extended equal accommodations in business establishments and public transportation to all persons without regard to race. Plantations were not broken up, nor was there a wholesale redistribution of land. The state militia was reformed, and surviving veterans of the War of 1812 were pensioned off. Articles that defined the executive, legislative, and judicial branches were much the same as those in the Constitution of 1852, which meant that state government would be as it was before the war and white men would regain control.

On paper this version of fundamental law may well have been the best of the ten constitutions. However, that is not how it was regarded by the majority of white Louisianans after 1868. Democrats savaged it as the plaything of ignorant Black people who they claimed were manipulated by corrupt carpetbagging Republicans. Its plan for a better, more equitable society fell apart in a political cesspool of racism, venality, and violence, and it was scrapped a decade later.

Constitution of 1879

In 1877 the crumbling of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of Federal troops allowed ex-Confederate Democrats to recapture control of state, parish, and municipal offices. Their unremitting corruption and chicanery ran up public indebtedness such that the state verged on bankruptcy. Facing near-certain financial collapse, the general assembly charged a constitutional convention to prevent it. One hundred thirty-four delegates, of whom only seven were Black, convened in April 1879. Although solving the fiscal crisis that brought them together, the Democrats seized the chance to minimize Black civil and political rights. They were finished in July, and in December 1879 the sixth constitution was ratified.

The Constitution of 1879 was an enormous document that consisted of 270 articles and several ordinances to relieve state debts. It distorted the differences between organic law and legislative policy by including numerous detailed articles that strengthened gubernatorial authority. Equally exhaustive restrictions limited the general assembly’s policy-making powers. Special interests were protected. On the other hand, the courts of appeal were created, and a homestead exemption was added to reduce taxes on homeowners. The constitution dealt gingerly with its diminution of Black civil and political rights. Instead of outright elimination, which risked federal intervention, it sharply circumscribed them. Guarantees of equal rights and free access to public places in the 1868 document disappeared. Gone, too, were articles that banned discrimination in public education or the establishment of segregated schools. Black men retained the franchise albeit with impediments that not only increased the difficulty for them to vote but for poor white men, too.

Despite those limitations, Black voters were still the largest voting bloc. For twenty years, that made them a threat to coalesce with poor white people and take control of state government. The Democrats ended the threats at the constitutional convention of 1898.

After 1879 the national government showed increasingly less interest in the fate of Louisiana’s Black population. Northern white people were also much less attentive as they reconciled with white Louisianans whose beliefs in the racial inferiority of African Americans mirrored theirs. The Democrats used their mastery of the general assembly to adopt Jim Crow laws. One of those laws was a statute that required railway passengers to be segregated by race and travel in separate carriages. Louisianans of African descent contested its legality all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the court upheld the statute, ruling that separate but equal seating on trains violated no one’s rights. The effect of the court’s holding was immediate and profound.

All that remained to finish the degradation of Black Louisianians was cancelling their right to vote. Rather than amend the Constitution of 1879, the Democrats engineered a call for the seventh constitutional convention, which met from February to May 1898 in New Orleans. When president Ernest B. Kruttschnitt opened deliberations, he called the convention “little more than a family meeting of the Democratic Party of Louisiana” that had been summoned to remove all the corrupt and illiterate voters who “degraded our politics.” Kruttschnitt’s “family meeting” did that and more before the delegates themselves ratified the new constitution.

A huge document, the Constitution of 1898 contained 326 articles. On the basis of separate but equal, Black people were defined constitutionally as second-class citizens with limited freedom of movement and civil rights. The suffrage article denied the vote to most Black men. It specified registry and literacy requirements. Voters had to own property, pay a one-dollar poll tax, and prove their grandfathers or fathers had voted before 1867 and the onset of Reconstruction.

A range of articles migrated from the old constitution intact. Supreme court justices were still gubernatorial appointees, although the chief justice succeeded to the center chair by virtue of seniority. (That precedent still exists.) Some modifications were tinged with whiffs of Populist-Progressive ideals: The desire for efficiency motivated the inclusion of boards and commissions composed of experts and private citizens to manage critical infrastructures. Ten articles added to the already long list of restrictions on the general assembly’s policy-making power. More exemptions lightened the tax burden on individuals, charitable institutions, and various special interests. As in the past, New Orleans was written into the constitution in a dozen articles that differentiated it from the rest of the state.

Although the constitution multiplied restrictions on the general assembly’s policy-making power, there was a loophole that politicians would exploit from 1898 to the present. Article 321 gave them sole authority to propose unlimited constitutional amendments at any meeting of the general assembly. If a proposed amendment passed both houses and the governor initialed it, it went to a vote in the nearest general election and was added to the constitution if it won the voters’ approval.

Taken as a whole, the Constitution of 1898 did two things. It legitimated white supremacy as the constitutional rule in Louisiana, and it fixed the Democratic Party as the ruler of the state. Those realities would not change for nearly a century.

Constitution of 1913

The Constitution of 1913 was a fiasco. It was written and adopted by a fifteen-day convention that was called to consider only two matters: refunding the state debt and addressing drainage problems in New Orleans. Choosing to expand the call, the delegates took on trust-busting, and modernizing juvenile justice and public administration. They also substituted an interpretation requirement for the grandfather clause. These and other changes resulted in an amended, confusing version of the constitution it replaced. Hasty draftsmanship resulted in parts that were merely references to past statutes or amendments instead of full texts. That flaw muddied the constitutional waters. Those waters turned muddier still in 1915 when the Supreme Court of Louisiana invalidated parts of the constitution because its authors had exceeded their mandate. That holding revived much of the 1898 instrument, and for six years the state was in the absurd situation of having two unmanageable constitutions.

Constitution of 1921

Governor John M. Parker called yet another convention to pull the state from its constitutional quagmire. It met for three and one-half months before it adopted Louisiana’s ninth constitution. The Constitution of 1921 was unique. It emerged from the convention as the longest of the ten constitutions, and it lasted longer than the others. What accounted for its uniqueness? An explanation is bound together with a desire to fix the existing constitution, the characteristics of the delegates, their agendas, their contrary visions of a constitution, and the absence of direction from Governor Parker or anyone else.

One hundred and forty-six individuals attended all or part of the convention. Two were white women and the rest were white male legislators, local politicians, or judges and lawyers. They represented a large number of factions within the Democratic Party, each with its own agenda. Progressive reformers pushed for a slender document that expressed fundamental principles only, whereas lawyers advocated modernizing the supreme court. Locals were determined to protect their special interests, and some wanted to incorporate more services. Other delegates favored only those revisions that were necessary to retreat from the quagmire. None of them would have abandoned white supremacy.

Governor Parker’s hands-off approach to the convention put the delegates in a complicated situation. Preparations were wholly inadequate. Law books, copies of former constitutions, or other working papers were initially unavailable. That unavailability extended the duration of the convention. More importantly, Parker’s refusal to lead left the delegates to themselves. They maneuvered the convention into a masterpiece of rambling, overly complicated language that ballooned their handiwork to a document of over one hundred pages.

The new constitution was derided as “a legal monstrosity.” There were expectations after 1921 that it would be replaced, but for fifty years, attempts to repeal it came to naught. Instead, it was amended, amended, and amended again before it was set aside in 1974.

Constitution of 1974

From the 1940s forward, government increasingly became rule by constitutional amendment as the general assembly piled amendment upon amendment to the constitution until the voters suddenly balked. In 1970 they rejected a batch of fifty-three proposals, and in 1972 they defeated another thirty-six, many of which affected only New Orleans. The consequence was a governmental crisis that needed to be solved promptly. Governor Edwin W. Edwards called the convention which wrote the most recent statement of Louisiana’s fundamental law, the Constitution of 1974.

“CC-73,” as the convention quickly became known, convened in Baton Rouge in January 1973. Most of the one hundred and thirty-two delegates were elected from the single-member districts of the state house of representatives. Twenty-seven were Edwards appointees, and all but one of these hailed from South Louisiana. Collectively they were lawyers, legislators, local officials, public employees, educators, tax assessors, as well as a supreme court justice and the vice president of the state American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). The membership also reflected changes wrought by the civil rights revolution, the push for equality between the sexes, and the revival of two-party politics. Black delegates had seats for the first time since 1879, there were more women, and there were the first Republicans since 1898.

Collectively, the delegates maintained what an observer described as “a fierce attitude of independence” that precluded interference from lobbyists or Governor Edwards. Their standing committees drafted all the reports that were eventually stitched into the new constitution. On its face the new charter had a different look. It was short, consisting of forty-three pages and just fifteen articles that included parts from the old constitution. Among them were a declaration of rights that forbade racial and sexual discrimination and another that stipulated home rule for parishes and municipalities. There were also provisions for limited state taxing authority, a twenty-member cabinet instead of over 250 state agencies, and a degree of environmental protection. The governor was term limited, and the number of educational boards was raised to five. Slimmed down, and unquestionably superior to the Constitution of 1921, the document had generous sprinklings of special interest legislation, nevertheless. That it did was no surprise, given that its architects spoke for special interests, as conventions had done ever since 1845.

Ratification was uncertain. Voters were indifferent or downright hostile. Newspapers were sharply divided as were the Republican Party and various interest groups. On referendum day nearly two-thirds of eligible voters stayed home, whereas voters in thirty-six of the state’s sixty-four parishes were against ratification. Some political trickery convinced voters in the New Orleans area that their interests were best served by the new constitution, and the immense weight of their numbers sufficed to carry the Constitution of 1974 into law.

Commentators guessed that after ratification the state would carry on much as it had in the past. They were right. Compared to other states, Louisiana ranked near the bottom of nearly all quality-of-life standards. Voters and special interest groups looked to the state government for services, but they adamantly opposed higher taxes. Crime, illiteracy, and poverty remained high. The racial divide narrowed, and race relations remained tenuous. Politicians still broke laws, though some wound up in prison. Government by constitutional amendment did not disappear. Since 1974 the constitution has been amended more than 300 times. That seems to be of little concern to anyone except scholars. Thus, it is questionable whether another convention will ever write an eleventh constitution for Louisiana.