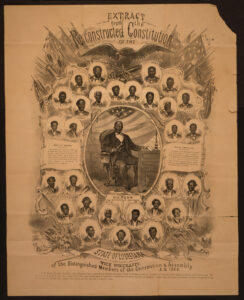

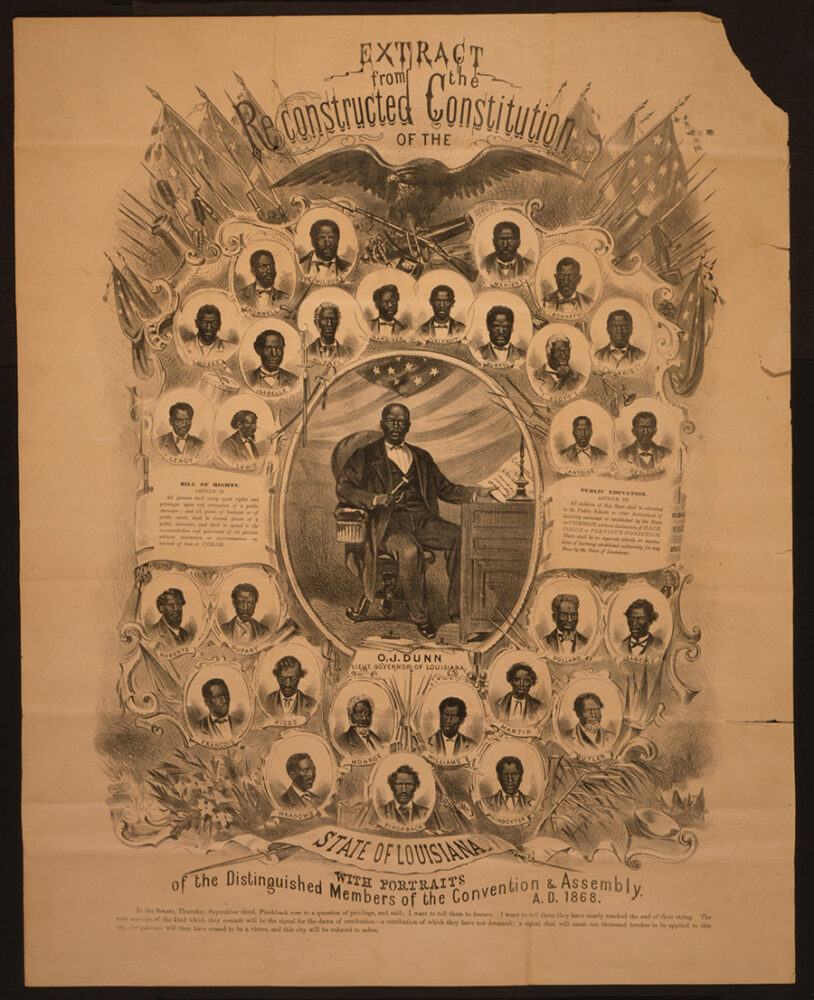

Louisiana Constitution of 1868

Following the Civil War, Black and white Republicans produced the Louisiana Constitution of 1868, which many regarded as one of the most progressive legal documents produced in the South during Reconstruction.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Extract from the Reconstructed Constitution of the State of Louisiana, 1868

Louisiana has functioned under an ever-changing cycle of constitutions. A feature common to each of the initial documents was their exceptionally restrictive nature. The initial constitution, produced in 1812, is regarded as one of the most limiting documents issued by any state in the Union. It placed strict limitations on the right to vote and hold office, denying the mass of Louisianans substantive political influence, and the branches of government created by the constitution possessed exceptional power. Responding to Jacksonian era calls for an expanded democracy, reformers produced the Constitution of 1845, which briefly curtailed some of the most egregious concentrations of power but also provoked a reaction from the state’s planter elite, who secured approval of a new constitution in 1852 that rolled back many reforms and reconcentrated power in the plantation parishes.

Provisions and Post-Civil War Development

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Radical Republicans in Congress, concerned that ex-Confederates would return to power in the South, passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 and called for new state constitutions. An equal number of Black and white Republicans met in convention and produced the Louisiana Constitution of 1868, which many regarded as one of the most progressive documents produced in the South. It was the first interracially written constitution in Louisiana and the first to include a bill of rights. The bill of rights extended citizenship and civil rights to all those men who remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. The document included provisions for integrated public schools and provided protections for the property rights of married women. It also included mandates for state care of the mentally ill and physically impaired citizens. The 1868 constitution similarly eliminated previous restrictions such as requiring property to hold office and serve on juries as well as imprisonment for debt. Such reforms proved far ahead of their time and opened the door to a seismic shift in Louisiana’s social structure and political culture.

“Loyal” Citizens

Despite the reformist vision of the 1868 document, like its predecessors, it included provisions and restrictions certain to render it unsatisfactory to Louisiana residents whose ability to vote would be negatively impacted by its provisions. Insisting that they were merely following the requirements of the federal Supplemental Reconstruction Act of 1867, the Radicals employed the “Ironclad Oath” requiring all voters to swear that they had never supported the Confederacy in any way—effectively disfranchising the vast majority of white voters in Louisiana. The Reconstruction Act specifically denied the vote to any who had “voluntarily” given aid to the Confederacy. The measure extended from Confederate soldiers to postmasters, sextons of cemeteries, and even farmers who sold grain to the Confederate Army. Unless granted amnesty the affected men were denied the right to vote until January 1, 1878, enabling Republican rule to become solidified. With such restrictions in place, Republicans elected ninety-six of ninety-eight delegates to the 1868 convention.

In the introductory comments to the Constitution of 1868, the delegates declared: “[R]ebellion is disfranchisement; we do endorse the acts of the thirty-ninth and fortieth Congress and will reconstruct Louisiana on the basis of the Reconstruction Bill. We are friendly to universal liberty, but no universal amnesty, but the continuance of disfranchisement of all Congress has and all others we may think necessary for the safety of our common country.” Some delegates acknowledged that denying the right to vote to more than half the state’s male population would doom the Constitution to failure. Prominent Black Republican leader P. B. S. Pinchback argued that universal suffrage remained a cardinal principle of the Republican party. Others called for punishment of Confederate leaders while offering leniency to men “who could not resist the force of overpowering circumstances.” Many others nonetheless supported the position of Wisconsin transplant Dr. Robert I. Cromwell, who advised that those opposing the convention’s provisions “could leave the country and go to Venezuela or elsewhere.”

Racial Consequences

Another concern that many delegates regarded as a threat to the sustainability of the 1868 Constitution centered on the provision for an integrated school system. A vocal group of delegates cautioned that white people would not send their children to racially integrated schools, and they cautioned about the consequences of requiring white citizens to pay taxes to support schools they would choose not to use. Others argued the mandate would destroy the school system at the outset, thus depriving children, especially newly freed Black children, of an education necessary to escape poverty. W. Jaspar Blackburn reminded his fellow delegates of the futility of legislating beyond what public opinion would accept.

Perhaps the most consequential omission of the Constitution of 1868 remained its failure to address the fundamental economic need of freedmen, specifically land. Lacking land to farm and otherwise develop, freedmen were left in economic limbo that offered freedom without the means to sustain themselves. Convention delegates discussed the paradox but in the end acknowledged that, barring a massive confiscation of land, few means existed to resolve the dilemma. As congressional legislation doled out thousands of undeveloped acres in Louisiana to railroads and other corporate enterprises, whose leaders partnered with members of Congress in the exploitation that characterized Reconstruction and its aftermath across the South, the freedmen, who sustained Republican power in Louisiana, never received the promised forty acres and a mule. This critical omission demonstrates that as radical as some provisions of the Constitution of 1868 may have been, it was not revolutionary.

Approval and Aftermath

The noble intent of many aspects of the Constitution of 1868 foundered on convention delegates making the same mistake as the creators of the state’s previous constitutions. Specifically, when Louisiana voted on the new constitution in April 1868, General Phillip Sheridan reported that nearly half the white male population remained disfranchised. Convention delegates were almost certainly correct: If the vote had been extended to ex-Confederates, they would have voted down the constitution by a large majority. But failure to make the effort, along with progressive provisions that may have been too bold for their time, ensured that at the close of Reconstruction one of the first acts of the new conservative state government was to call for a new constitution. The resulting Constitution of 1879 realigned the state as close to pre-Civil War conditions as possible without violating the federally imposed provisions of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.