1795 Point Coupee Slave Conspiracy

Enslaved, free Black, and white people planned an insurrection to end slavery in Spanish colonial Louisiana roughly 150 miles north of New Orleans.

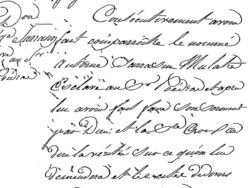

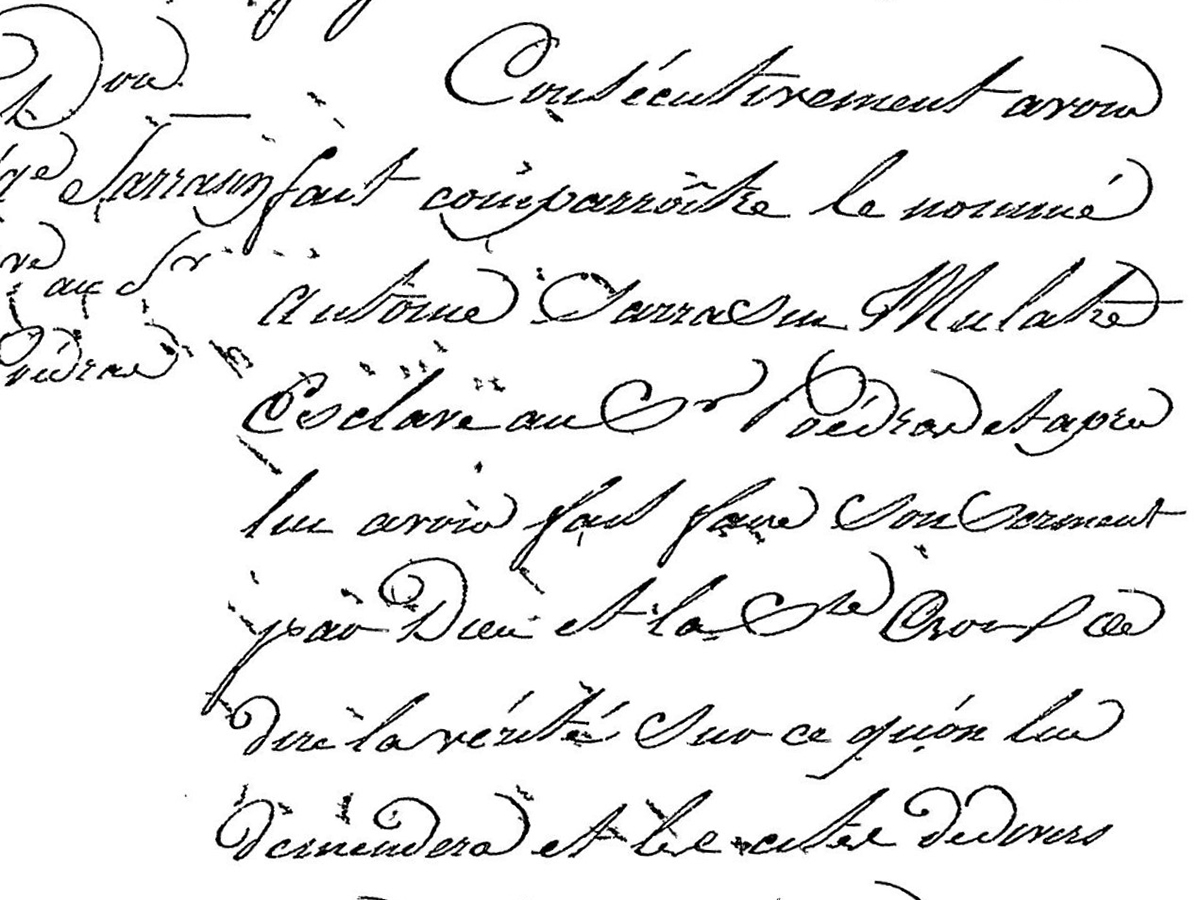

Pointe Coupée Parish Clerk of Court’s Office via Louisiana Slave Conspiracies

Portion of declaration of conspiracy leader Antoine Sarrasin, 1795.

The 1795 Point Coupee slave conspiracy was a planned slave insurrection that was broken up by Spanish authorities before its members began to revolt. The conspiracy was influenced both by the desire of individual enslaved people to be free and a growing movement among Black people and radical white people to end slavery in Louisiana. Governor Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet y Bosoist, Baron of Carondelet, ordered his militias and local planters to round up conspirators and suspected participants, tried them, and then executed or exiled most of them. This conspiracy is well documented because of the detailed trial records that the Spanish colonial government compiled as they investigated and subsequently punished the conspirators.

Background and Planning

Point Coupee was an area with several large plantations—including the Poydras estate where the conspiracy was organized—located roughly 150 miles north of New Orleans along the Mississippi River. In many ways Point Coupee was a frontier area, far from any other major settlements, and often in contact with Indigenous tribes. In Point Coupee there were more than twice as many enslaved people as white people. This imbalance, combined with the remote location, was a source of inspiration for the area’s enslaved people, who knew they greatly outnumbered the white planters and overseers.

According to the Spanish interrogation records, Antoine Sarrasin was the main leader of the conspiracy, along with Jean-Baptiste, Enstanislao Anis, and Auguste Bergeron. Their plans involved uniting enslaved people from several different plantations to kill local enslavers, acquire their guns and ammunition, and then instigate a broader revolt in the area. While the location was far from New Orleans, the enslaved people of Point Coupee were well informed about the revolutionary politics of the area, both by sympathetic white settlers and by the informal networks of information sharing up and down the Mississippi. Beyond their individual desires for freedom, the leaders were inspired by the success of the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791, by the rhetoric of the French Revolution, and by the abolition of legal slavery by France in its territories and colonies in 1794. Spanish trial records indicate that a copy of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” which declared all men to be free and equal, found in Point Coupee was potentially supplied by Joseph Bouyavel and Jorge (George) Rockenbourg, two white men who were political dissidents arrested and exiled by Spanish authorities.

Spanish Response

The Spanish response to reports of a conspiracy by enslaved people in Point Coupee was quick and definitive. Initial actions to contain and investigate the conspiracy were taken by Guillermo Duparc, the local post commandant who immediately began arresting and interrogating enslaved people to repress the conspiracy. Local enslavers also took action to investigate people they enslaved but were initially wary because they feared the economic impact on their income if large amounts of enslaved people, on whose free labor they depended, were imprisoned or executed. Soon Governor Carondelet became involved and sent militia forces from New Orleans to aid in the repression.

Ultimately more than sixty people, who were mostly but not exclusively enslaved, were put on trial for their participation in the conspiracy. Twenty-three of them (all of whom were enslaved) were sentenced to public execution by hanging by Governor Carondelet, with the rest sentenced to combinations of prison, hard labor, and exile. Three white people convicted of aiding the conspiracy were exiled from Louisiana and sentenced for six years of hard labor in Havana. Although the planned revolt failed, it still had a major effect on the politics of slavery in Spanish colonial Louisiana, as Governor Carondelet immediately issued new restrictions on the lives of enslaved people aimed at keeping them isolated, unarmed, and compliant.