Battle of Baton Rouge (1779)

Spanish colonial capture of British forts on the Mississippi River during the American Revolutionary War provided significant strategic and symbolic victories.

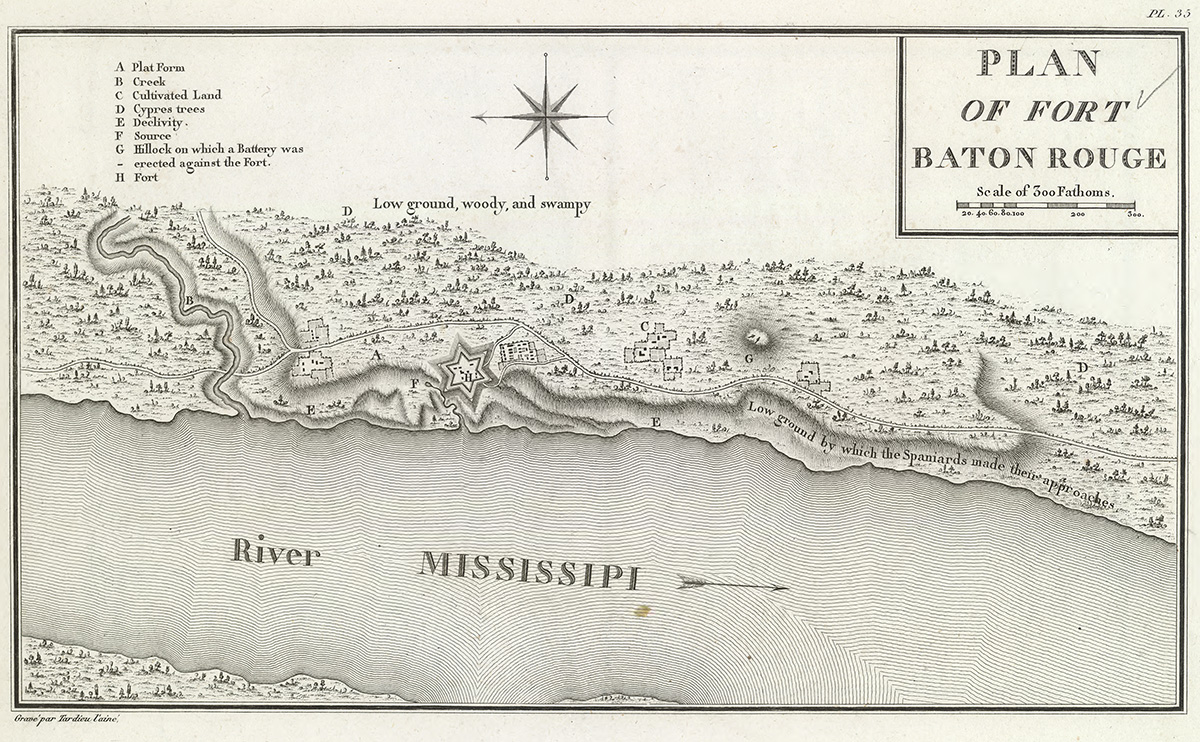

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Fort Baton Rouge as depicted in Georges-Henri-Victor Collot's book Voyage dans l'Amérique Septentrionale, 1826.

The Battle of Baton Rouge was the culminating military victory in Spanish colonial governor Bernardo de Gálvez’s campaign against British forts along the Mississippi River. It occurred during the American Revolutionary War, shortly after Spain had declared war on Great Britain and openly joined the war on the side of France and the Continental Congress. Gálvez’s capture of the strongly garrisoned fort at Baton Rouge also forced the surrender of the upriver British fort at Natchez, and it effectively ended British military control of the lower Mississippi River and the westernmost portions of British West Florida, which included today’s so-called Florida Parishes in southeast Louisiana.

Preparations for War

Although Spain was not yet at war with Great Britain when Gálvez arrived in Louisiana in late 1776, he began preparing for the possibility of it. He improved local defenses, worked to increase the number of militia and army troops, and sent spies to learn about British military preparations in the neighboring province of British West Florida. The British maintained three forts on the lower Mississippi River that could threaten New Orleans: Fort Bute at Manchac, a recently constructed fort in Baton Rouge, and Fort Panmure in Natchez.

The formal war declaration was made in Spain in June 1779. Gálvez did not receive official notification until that August, but his spy network provided timely warning of enemy war preparations. For example, he learned that the British fort on Bayou Manchac had been heavily reinforced with four hundred men, most likely to support a British attack on New Orleans at the first hard news of hostilities between England and Spain. Intercepted letters addressed to a British official at Natchez confirmed this suspicion. While eager to strike first, Gálvez carefully disguised the nature of his own preparations. When he received official notice of the declaration of war by Spain upon Great Britain, he made no public announcement, not wanting word to get to the British forts upriver before his forces could reach them.

However, Gálvez’s planning was interrupted by the sudden and unexpected arrival of a hurricane on August 18, 1779. His boats and supplies were sunk, many buildings were damaged, and it seemed that even restoring the city’s defenses would be difficult. Fortunately, Gálvez was able to rally his officers to quickly restore New Orleans’s defenses and re-equip his troops before the British could attack from their undamaged forts. His forces departed the city on August 27, a mere four days after their planned departure.

Under Gálvez’s command were 170 veteran regular army troops, 330 new recruits from Mexico and the Canary Islands, twenty mounted cavalrymen, sixty citizen militiamen and volunteers, eighty free men of color, and seven American volunteers, including businessman Oliver Pollock, an agent of the Continental Congress. Gálvez’s total force as it left the city was 667 men. They had to march over difficult terrain, through woods and water, keeping pace with their supplies on the river. They had no tents and lacked other essential supplies, but their spirits were high. At the German Coast (in modern St. Charles and St. John the Baptist Parishes), Gálvez collected additional militia companies along with 160 fighters from Indigenous tribes, including Houmas, Choctaws, and Alabamas, raising his forces to more than fourteen hundred men, though this number was reduced by one third due to sickness and the rigors of the fast march upriver.

First Victory at Fort Bute

On September 2 Gálvez’s column came within sight of Fort Bute, a log fort on Bayou Manchac. There, Gálvez finally announced that war had broken out between Spain and Britain and that he was ordered to attack the British posts on the Mississippi. The news was received with cheers. Upon seeing the Spanish advance, the main British garrison withdrew, and only a small number of troops held the fort. Gálvez sent a detachment to cut off the fort from Baton Rouge so that it could not be reinforced and then ordered an assault by the militia. These men stormed the fort, killing one British soldier and capturing two officers and eighteen men. Though it was not a great battle by most standards, the citizen soldiers had performed well, and they were heartened by their victory, especially the Acadians, who well remembered their persecution and exile from British Canada.

The Siege at Baton Rouge

With Fort Bute under his control, Gálvez wasted little time in continuing upriver. The fort at Baton Rouge was much more formidable than the one at Manchac and could not be taken by a direct assault. It was surrounded by a ditch that was eighteen feet wide by nine feet deep, protected by earthen walls and wooden palisades, mounting thirteen cannons, and garrisoned by about four hundred regular army troops, as well as approximately one hundred armed settlers and enslaved men. They were expecting Gálvez and his men, so a surprise attack or direct assault would not be possible. Gálvez knew that a prolonged siege would cost lives. He had to attack, but he also knew that many of his militiamen and volunteers were heads of families and that his colony would be filled with grief if he carelessly got them killed. In the end Gálvez decided to use diversion and misdirection, seizing the advantage of a grove of trees several hundred yards from the fort. Here he sent a detachment of white militiamen and free Black and Indigenous troops to noisily cut down some trees, build an earthwork, and generally make so much commotion that they would attract the entire attention of the British garrison. As they did so, English gunners blazed away at them all night long, fortunately without wounding a single man.

When dawn arrived the English were astonished to find Gálvez’s artillery dug in and ready on the opposite side of the fort, away from the grove, firing at them from close range with devastating effect. The British garrison tried to redirect their fire, but it was too late; the Spanish gunners were too well protected. Walls and British guns were smashed by Spanish cannon fire. By mid-afternoon the fort at Baton Rouge was compelled to surrender. Gálvez pressed for hard terms: the British commandant, Lt. Colonel Dickson, was advised to include in his surrender Fort Panmure at Natchez, garrisoned by eighty troops. Dickson agreed to these terms, and twenty hours later, he and his men marched out of the fort, delivered their weapons, and became prisoners of war. In one bold stroke, in September 1779, the forces of Spanish Louisiana ended British control of the Lower Mississippi and effectively re-conquered the western half of West Florida.

Aftermath

Gálvez’s captures of the British forts on the Mississippi River were significant strategic and symbolic victories. He ensured the safety of New Orleans, bolstered the confidence of his army and militia troops, and put the remaining British forces in the region on the defensive. In the two years that followed, Gálvez completed his conquest of British West Florida by capturing Mobile and Pensacola.