Florida Parishes of Louisiana

A portion of Louisiana was once the western extremity of colonial Florida

Library of Congress

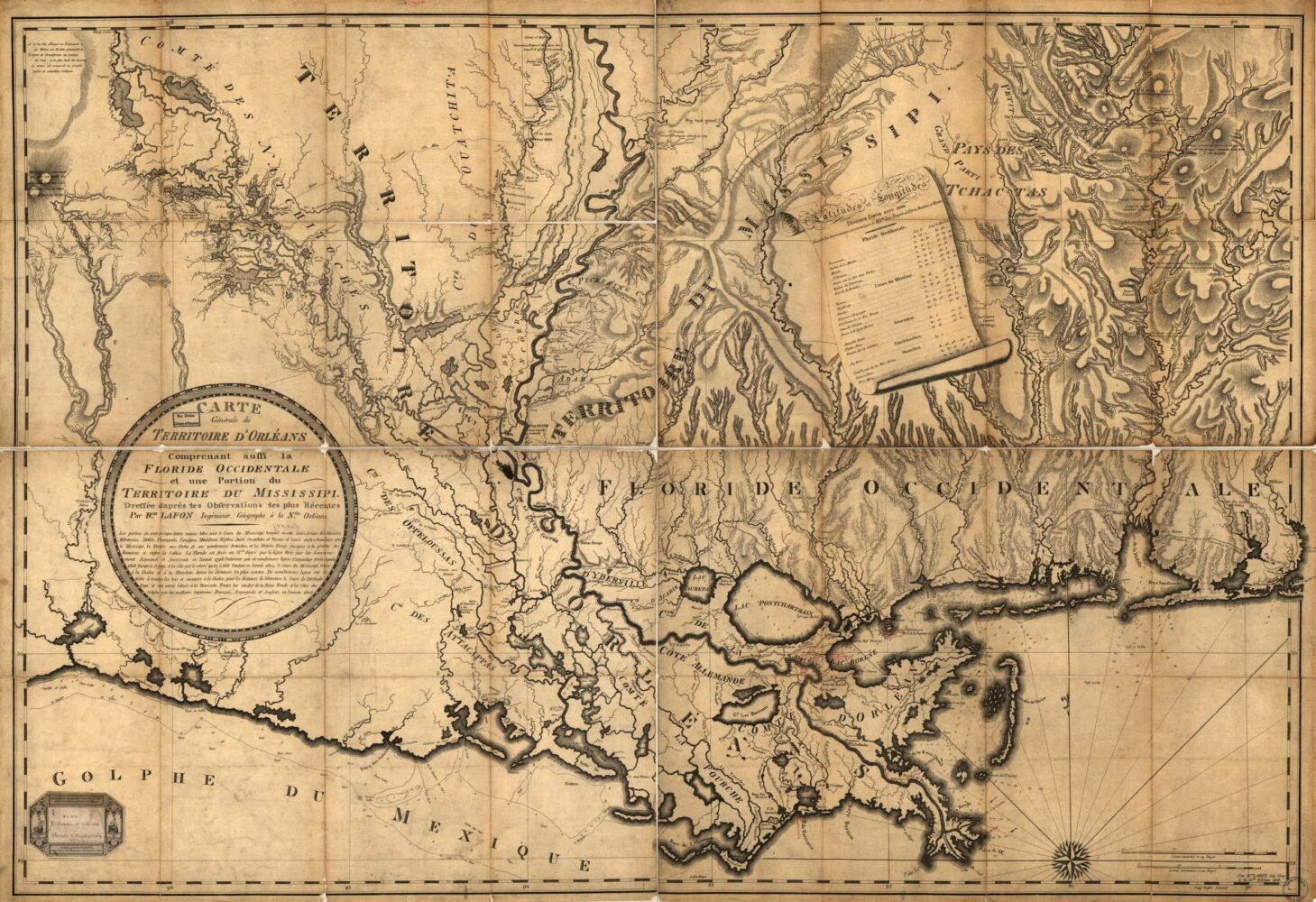

This map of the Orleans Territory, produced by Barthélémy Lafon in 1806, also shows West Florida, labeled in the lower right quadrant as "Floride Occidentale."

Wedged between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi state line, the area of Louisiana known as the Florida Parishes has lived under Choctaw, French (1717–1763), British (1763–1779), and Spanish (1779–1810) rule. In 1810 the region was annexed by the United States, but not before a brief existence (seventy-four days) as the independent Republic of West Florida.

The region encompasses six parishes: St. Helena (1810), named for St. Helen, the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great; St. Tammany (1810), named for Tamanend, a Delaware Indian chief who became a symbol of American resistance to the British; Washington (1819), named for the nation’s first president; East Feliciana (1824), named for Félicité de Gálvez, wife of Louisiana territorial governor Bernardo de Gálvez; Livingston (1832), named for US Secretary of State Edward Livingston; and Tangipahoa (1869), named for the Tangipahoa Indians. The eastern boundary is formed by the Pearl River, so named because of the lowgrade pearls found there, and the southern boundaries are Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Maurepas. The narrow waterway between the two lakes, now known as Pass Manchac, provided the shortcut that the Indians showed to Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d’Iberville, and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, in 1699. The region’s terrain is hilly in its northernmost parts. Before the big lumber companies arrived in the late nineteenth century, most of this area was densely covered with longleaf yellow pines that reached heights of one hundred feet. Cypress swamps lie to the southwest.

Native Americans, notably the Choctaw, inhabited the region before settlers of European ancestry began to arrive, many of them from the East Coast. Some early European settlers carved small farms out of the forests, raising cattle and growing mixed crops. The wealthier settlers brought enslaved people with whose labor they established cotton plantations. In the northern and eastern sections, log cabins, including dogtrot houses, were common, and in the western areas, Greek Revival forms were adopted with enthusiasm. The towns of Clinton and Jackson in East Feliciana Parish are showcases of Greek Revival architecture.

In the mid-nineteenth century New Orleanians discovered the pure pinescented air and natural springs along the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain and traveled by boat to this “ozone belt” across the lake. Health resorts and hotels quickly sprang up. But in general the area remained thinly settled until the railroads arrived. The Illinois Central Railroad, for example, encouraged settlement by issuing pamphlets such as The Farmer’s Road to Wealth, Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana. Such promotion encouraged hundreds of immigrants from Iowa, Michigan, and Illinois to relocate to this area. Hungarians formed a large rural colony at Árpádhon in Livingston Parish. Italian immigrants also used the railroads, cultivating cutover pine lands for strawberry production and shipping the fruit to Chicago in refrigerated freight cars. Among the towns that formed at the railroad stops, which were placed at ten-mile intervals alongside the tracks, are Ponchatoula, Amite, Tangipahoa, and Albany. Also, lumber companies established mills and towns. By the early 1900s there were thirty pine sawmills in Washington Parish alone, including, in Bogalusa, what was said to be the largest pine mill in the world. In addition to pine, cypress was harvested from the swamps beside Lake Maurepas.

Today, crop and dairy farming and lumber remain important to the economy. The southern sectors of the Florida Parishes, particularly St. Tammany Parish, have experienced extraordinary population growth. In 1956 the Causeway linking New Orleans to Lake Pontchartrain’s north shore was completed; at twenty-four miles, it was the longest highway bridge in the world at that time. With completion of the second span in 1969, New Orleanians began relocating across the lake in greater numbers. The formerly small towns of Covington and Mandeville have become bedroom communities for New Orleans and have expanded outward with many new subdivisions. By the early 1990s, suburban sprawl, overcrowded schools, and traffic congestion had become substantial problems that would take years to effectively address.