Coushatta Massacre

The 1873 Coushatta Massacre resulted from both anger about Reconstruction policies and the presence of carpetbaggers in the state.

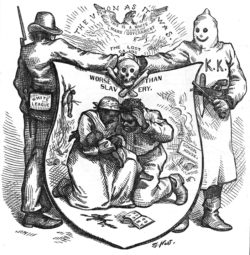

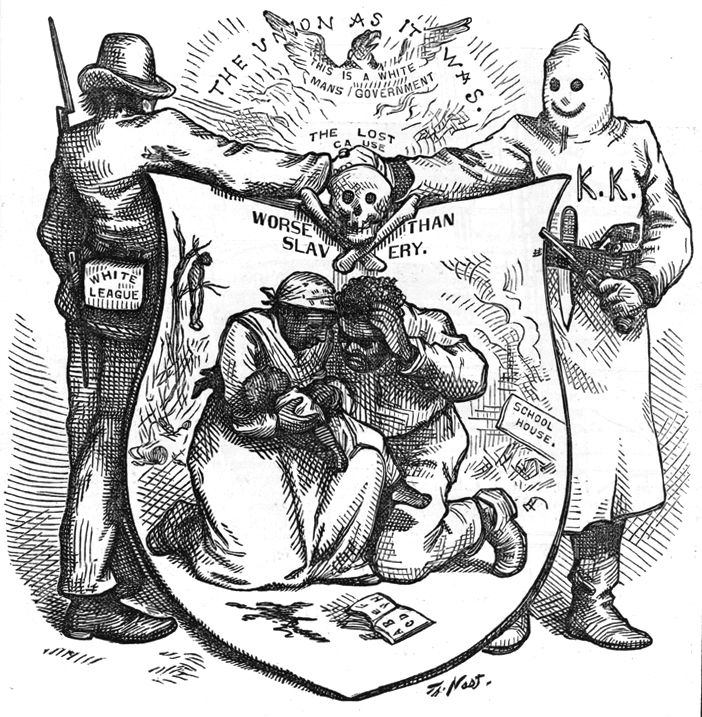

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

"The Union As It Was". Nast, Thomas (Artist)

Editor’s Note: Warning, this entry contains graphic imagery.

The Coushatta Massacre was an important event in the overthrow of Radical Reconstruction in Louisiana. On the upper Red River, during the last week of August 1874, the White League murdered ten Republicans: four blacks and six whites. Nine of the murdered men were from Red River Parish; one was a De Soto Parish official. The killings all had the same end: the destruction of Republican government in northwestern Louisiana.

The valleys of the Red River and the Mississippi River form a huge topographical Y that cuts through the heart of Louisiana. Radical Reconstruction was the program of the Republican Party, and Republican rule in the state rested on African American votes, which were concentrated in the alluvial bottomlands of the Y. The smaller and weaker arm of the Y was the Red River Valley, hence the importance of Red River Parish, which was the bailiwick of the Twitchell family, who were post-Civil War emigrants from Vermont (i.e., carpetbaggers, in the language of Reconstruction).

In fall 1865, Captain Marshall H. Twitchell, formerly a white officer in the U.S. Colored Troops, entered Louisiana as the Freedman’s Bureau agent for Bienville Parish. He left the Bureau in mid-1866 and married Adele Coleman, the daughter of Isaac Coleman, a prominent Bienville Parish planter. Twitchell bought a plantation on the eastern shore of Lake Bistineau and became the business manager of the combined Coleman-Twitchell estates. He served as Bienville Parish’s delegate to the state’s radical constitutional convention of 1867–1868. In 1869–1870, he bought Starlight Plantation in De Soto Parish and won election to the state Senate. During these years Twitchell’s brother Homer, his three sisters and their husbands, and his mother relocated from Vermont to his Louisiana properties. Other northerners also settled near Starlight, creating a “Yankee colony” in this isolated outback of the old Confederacy.

In the upper Red River Valley parishes were large, courthouses distant, and transportation primitive. Residents of the central valley between the towns of Shreveport and Natchitoches had long desired the creation of a new parish to make local government in the region more convenient. In 1871, Twitchell and a De Soto Parish ally sponsored the bills that created Red River Parish, carved out of portions of De Soto, Bienville, Caddo, Bossier, and Natchitoches parishes. The town of Coushatta, across the river from Starlight Plantation, became the parish seat. Twitchell became the local political boss and established the first public schools in the region, segregated by race. Aside from his insistence on black education, businessmen and planters in the region generally applauded Twitchell’s actions. The creation of the new parish coincided with the first signs of economic recovery since the war, Coushatta merchants prospered, and, for a brief moment, Republican governance was acceptable, if not genuinely popular, with whites.

Resentment of Twitchell and his Yankee colony remained just beneath the surface, though. The Panic of 1873 and a concurrent yellow fever epidemic devastated the region. Yellow fever claimed the lives of some of Coushatta’s first citizens and stifled commerce. The financial panic dried up credit and drove many of the parish’s leading planters and merchants out of business. Bad weather and the army worm destroyed much of the cotton crop. The corn crop failed as well. “It really does seem,” the Coushatta Citizen commented in November 1873, that our people “have struggled against more disasters, undergone greater hardships, and lived harder and had less credit this year than ever before.”

Hard times were hardly limited to Red River Parish—or Louisiana; the panic engulfed the entire South. Southern whites found a ready scapegoat in “Negro-carpetbag rule,” as they typically described Republican governance. A Democratic “white line” strategy emerged in the Deep South dedicated to restoring white supremacy. In Louisiana the strategy took the form of the White League, which first appeared in the lower Red River Valley and spread rapidly across the state. Though the name was new, the White League was less a new party than it was the Democratic Party, reinvigorated. The membership of the White League and the Democratic Party were virtually identical. In the summer of 1874, Red River Parish merchants and planters organized the White League in Coushatta under the leadership of Thomas Abney.

Before moving on Coushatta, White Leaguers struck the town Natchitoches, twenty-seven miles downriver from Coushatta. In late July the Natchitoches White League, aided by Abney, Joseph Pierson, and other Coushatta men, seized the Natchitoches Parish government. Marshall Twitchell was in New Orleans at the time. Red River Parish sheriff Frank Edgerton wrote him a few days after the Natchitoches coup: “Pierson & Abney came back from Natchitoches red hot and on the war path.” Their intentions are clear: “It is simply extermination of the Carpet bag and Scalawag Element. Nothing more nor less.”

In the weeks that followed, Twitchell remained in New Orleans while tension mounted in Coushatta. Around midnight on August 25, whites murdered Thomas Floyd, a black Republican in the Brownsville community, south of Coushatta. Floyd’s murder set in motion the violent events that followed. Two days later, the Red River White League arrested six prominent white Republicans on the pretext that they were plotting a murderous Negro rebellion: Homer Twitchell (tax collector and brother of Marshall), Sheriff Edgerton, William Howell (parish attorney), Clark Holland and Monroe C. Willis (minor officials and brothers-in-law of Marshall Twitchell), and Robert Dewees (De Soto Parish tax collector). At the same time, League leaders rounded up twenty black Republicans.

News of a Negro uprising raced through the upper Red River Valley and within forty-eight hours hundreds of heavily armed whites from neighboring parishes and the Texas border country descended on Coushatta. The angry outsiders thronged the streets, swearing, drinking, and demanding blood. The Republican prisoners, confined in the basement of Thomas Abney’s store, were terrified, and one of them asked, “Where in the name of God did all these people come from?”

On Saturday, August 29, a panel of Coushatta’s leading citizens conducted a star-chamber trial of the white prisoners. Late in the day, after hours of merciless grilling, Homer Twitchell, Sheriff Edgerton, and the other white prisoners, in return for a promise of safe passage to Shreveport, resigned their offices and promised in writing to leave the state and never return. At the same time, the White League issued a proclamation over the signatures of Abney, Pierson, Julius Lisso, and other town leaders, alleging that the prisoners were evil men who had indoctrinated “vicious ideas into the minds of the colored people of Red River, and array[ed] them against the true interest of the country.”

Abney chose a guard of about twenty-five men, and mid-morning on Sunday prisoners and guards, mounted in column, headed up the river toward Shreveport. Near 4:00 PM, the column, now strung out with the prisoners in front, crossed the line into Caddo Parish, twenty miles below Shreveport. Minutes later, guards at the rear of the group spied forty or fifty heavily armed riders in hot pursuit. The pursuers were led by a mysterious “Captain Jack”—his real name Dick Coleman—about whom almost nothing is known except that he liked to kill Republicans. Captain Jack’s gang overtook the train, crying out to the guards, “Clear the track,” or die with the prisoners. Dewees, Homer Twitchell, and Sheriff Edgerton died in the first hail of bullets. The lynch mob took Howell, Willis, and Holland prisoner, then executed them in cold blood. At no point did the guards make any effort to protect the prisoners.

In the meantime, south of Coushatta, whites seized a black leader named Levin Allen, broke his arms and legs, and burned him alive. Then, on Monday, the Coushatta White League conducted a mock trial of two of the black prisoners confined in Abney’s store, Louis Johnson and Paul Williams, allegedly for shooting a white man. Captain Jack’s mob, returned from their bloody work upriver, seized Johnson and Williams and hanged them.

Although four black men died in the Coushatta Massacre, it was the murder of white officeholders that grabbed newspaper headlines across the nation. Coushatta marked a dramatic escalation of Reconstruction violence. The officialdom of an entire parish—and white men at that—had been virtually decapitated in a single murderous act. The Coushatta Massacre stunned Republicans in every corner of Louisiana. If the White League could take the officials of an entire parish and simply gun them down with impunity (none of the lynch mob would ever be brought to justice), then Republican governance was a hollow shell. The massacre occurred just two weeks before the White League routed Republican forces in the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans. Republican governance in the state never recovered from these savage blows.

Two years later, Captain Jack shot down Marshall Twitchell and his sole surviving brother-in-law, George King, on the east bank of the Red River. King died instantly; Twitchell survived but both of his arms had to be amputated. He left Coushatta on a stretcher in the summer of 1876, never to return.