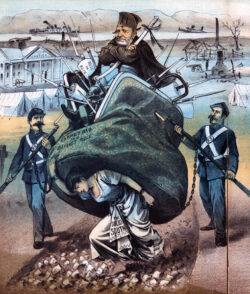

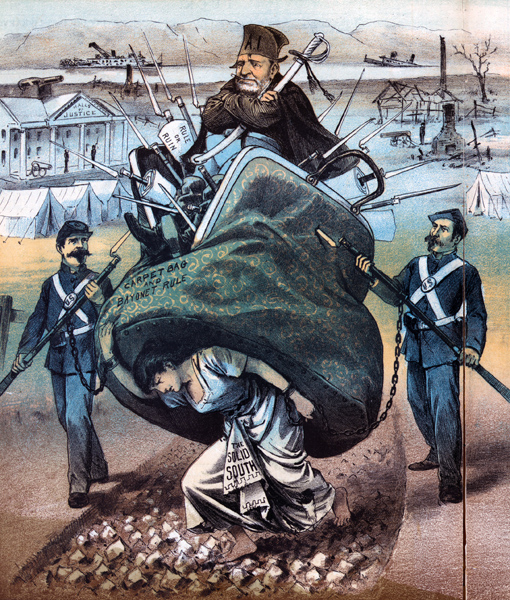

Carpetbaggers and Scalawags

“Carpetbagger” and “scalawag” were derogatory terms used to deride white Republicans from the North or southern-born radicals during Reconstruction.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The "Strong" Government. Wales, James Albert (Artist)

Carpetbagger” and “scalawag” are derisive epithets which southern Democrats, or Conservatives, applied to white Republicans, or radicals, during Congressional or Radical Reconstruction. Carpetbagger referred to Republicans who had recently migrated from the North; scalawag referred to southern-born radicals.

Words such as carpetbagger and scalawag are ideographs, symbolic words so resonant with political imagery and meaning that they influence political behavior. As such, they were invaluable to the white South’s Counter-Reconstruction movement that commenced within months of the Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867, and lasted, with only periodic abatement, until the last Republican governments in the South were overturned in 1877. Like Radical Reconstruction itself, Counter-Reconstruction was structured around ideology, or worldview. As ideas, carpetbagger and scalawag were key components of that Counter-Reconstruction worldview. The words depicted the white advocates of Reconstruction as disgraced and degraded men who put themselves on a level with Black people. To defeat such villains, the end justified the means—fraud, intimidation, and terrorist death squads. Modern historians have long since discredited the white South’s morality play depictions of carpetbaggers and scalawags and would, if they could, dispense with the words themselves. But the words are embedded in the history of the era. Historians still use them devoid of their negative associations.

Radical Change

The Reconstruction Act, the basis of Radical Reconstruction, instructed the former Confederate states to elect delegates to constitutional conventions and adopt new constitutions. The ensuing conventions of 1867 and 1869 were overwhelmingly Republican in party identity and culture. For southerners, white and Black, Republican and Democratic, these bodies marked the real beginning of radicalism. It was in these bodies that Black suffrage and civil rights became real issues, to be debated and voted on; it was in these bodies that Black politicians, northern newcomers, and native-born radicals began to exert real power. It was in response to these conventions, moreover, that Counter-Reconstruction began.

Although it was not the case in Louisiana, across the South the largest single group of Republicans elected to the conventions were native white southerners, most of whom had been unionists during the Civil War. Building a vocabulary to discredit the conventions and those who served in them, Democratic editors in the Deep South branded these men “scalawags.” The word probably dates back to an old Scottish village Scalloway, which two centuries before had become eponymous with scraggly, inferior livestock. “From time immemorial,” a Mississippi editor wrote, scalawag has referred to “inferior milch cows in the cattle markets of Virginia and Kentucky.” The word, though, had also come to mean any shiftless scamp or ne’er-do-well on the fringe of human society. In early 1868 an Alabama editor defined scalawag in its new Reconstruction context:

“Our scalawag is the local leper of the community. Unlike the carpetbagger, he is native, which is so much worse. Once he was respected in his circle . . . and he could look his neighbor in the face. Now, possessed of the itch of office and the salt rheum of Radicalism, he is a mangy dog, slinking through the alleys, haunting the Governor’s office, defiling with tobacco juice the steps of the Capitol, stretching his lazy carcass in the sun on the Square, or the benches of the Mayor’s court.”

In labeling native-born radicals as scalawags, southern editors created a powerful and enduring Counter-Reconstruction symbol.

Scalawags in Louisiana

As elsewhere in the South, most scalawags in Louisiana were the unconditional unionists of 1861–1862. Some of these individuals, such as James Madison Wells (governor during Presidential Reconstruction) and James G. Taliaferro (president of the constitutional convention of 1867–1868 and later chief justice of the State Supreme Court), hailed from the upstate cotton region. The majority, though, were products of the northern-born and foreign-born communities of New Orleans and southeastern Louisiana. The business, professional, and civil life of antebellum New Orleans had been largely dominated by northern-born migrants and, to a lesser extent, immigrants from Ireland and Germany. With their Yankee and foreign backgrounds, such naturalized southerners exhibited a worldliness and commercial vision that made them skeptical of secession and its adherents. Then, too, they lived and worked in the most cosmopolitan city in the South. Out of all proportion to their numbers, such transplanted Yankees and foreigners were unionists during the war, then Republican scalawags during Reconstruction. One study of ninety-seven New Orleans unionists, for example, found that more than 81 percent had been born outside the eleven Confederate states. Wartime Louisiana governor Michael Hahn had been born in Germany. Free State leader Thomas J. Durant was a native of Pennsylvania. Indeed, of the seven state officials who headed Louisiana’s Free State government in 1864, only one was a native southerner.

Unionists/scalawags had their greatest influence in Louisiana in the period from 1862 to 1867. Black politicians dominated the radical constitutional convention of 1867–1868. True, scalawags held most of the seats in the state legislature between 1868 and 1877, but legislative majorities did not translate into hegemony. Carpetbaggers controlled the vital levers of state power throughout Radical Reconstruction.

The Arrival of Carpetbaggers

During or shortly after the Civil War, several thousand northerners migrated into the South. The great majority of these men had served in the Union Army and seen duty in the South. They were men in their twenties and thirties who saw the postwar South as “a new frontier, another and better West.” They came as cotton planters, businessmen, teachers, lawyers, physicians, and so on. As a group, they were well educated; indeed, they were probably the best educated class of men in American politics, a disproportionate number of them having college educations. These northern migrants were a minority, though a very influential minority, in the Reconstruction conventions.

In late 1867, an Alabama editor coined the word carpetbagger to describe them, a term the New Orleans press quickly adopted. In December 1867 the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin wrote a classic description of “the volatile patriots who come from the North to reconstruct the South upon a proper basis. . . . The man with the carpet bag has very little ‘whereby he may be attached.’ He is prospecting politically. If he finds a living without capital or labor, he hangs up his carpet bag.” But “if times are hard or troubles impending, his ‘shirt for superfluity’ is called in from the wash; his bill, settled or unsettled, offers little impediment, and he may take the evening train.” Such northern fellers “go through the South to put up constitutional machinery, just as they might be sent out to put up lightening rods or cotton gins. They come as shadows, but they sometimes depart full and well stuffed.” Like that of the scalawag, the image of the greedy carpetbagger would be embossed in the history of the era.

Carpetbaggers in Louisiana

Union forces occupied New Orleans in May 1862 and remained for the duration of the war. Tens of thousands of federal soldiers, treasury agents, planter lessees, and other northern officials lived in the city and its environs during the long occupation. For this reason, carpetbaggers were more numerous and more powerful in Louisiana than in any other southern state. Both Louisiana governors under Radical Reconstruction, Henry Clay Warmoth (1868–1873) and William Pitt Kellogg (1873–1877), were carpetbaggers. The state elected three US senators in the radical years, all carpetbaggers. Ten of the thirteen congressmen sent to the US House of Representatives in the period were carpetbaggers. Even though northerners were always a small minority in the state legislature, the speaker of the House for most of the period was a carpetbagger. Then, too, carpetbaggers dominated the large federal bureaucracy concentrated in New Orleans—the Custom House, the Mint, the Post Office, the Land Office, the Internal Revenue Office, and the Fifth Circuit Court. Control of the federal bureaucracy meant jobs for Republicans, always at a premium because white Democrats controlled the great bulk of the state’s land and business wealth. Indeed, in the early 1870s, federal jobholders known as the Custom House Ring played a decisive role in state politics, driving Governor Warmoth from office and paving the way for one of their own, William Pitt Kellogg—a former collector of the Port of New Orleans—to become governor. In fact, the incessant infighting among Louisiana carpetbaggers in the 1870s played an important role in undermining Reconstruction in the state and the region.