Father Paul Du Ru

A Jesuit priest was the first to establish Catholic missions among the Indigenous peoples of the Gulf South.

Newberry Library

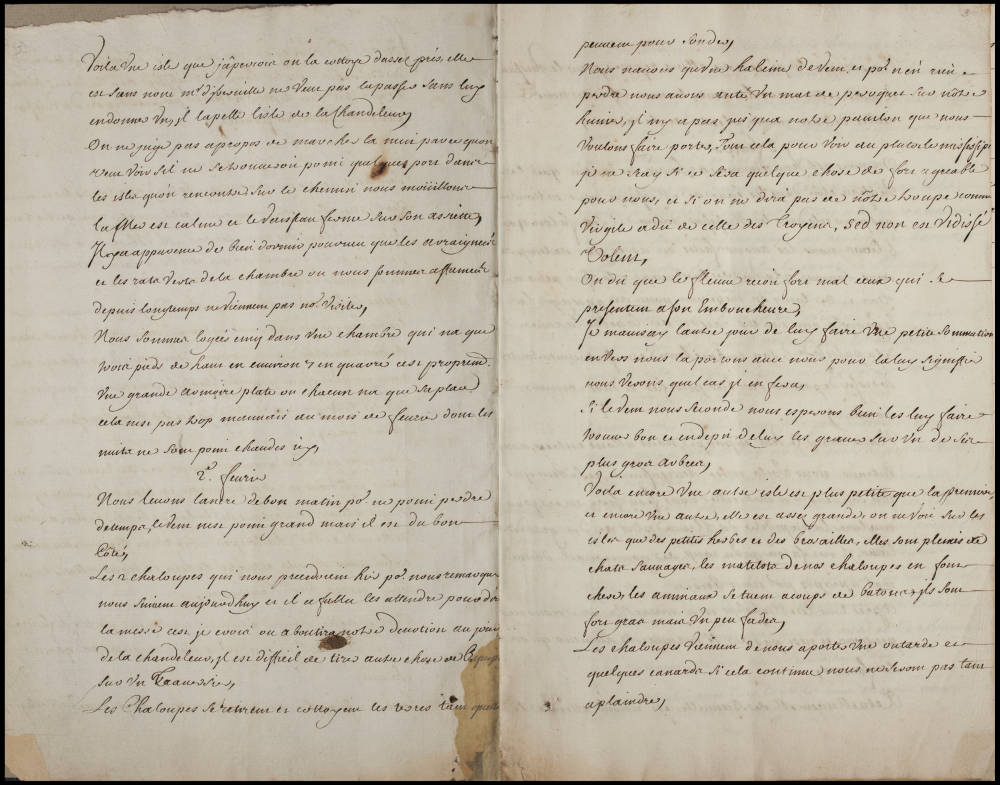

Jesuit chaplain Paul Du Ru's journal, 1700.

Father Paul Du Ru was the first Jesuit priest to attempt to establish Catholic missions among the Indigenous peoples of the Gulf South. Arriving in 1700 he traveled throughout the region for two years making the first efforts to provide Catholic education to Indigenous peoples in French colonized Louisiana. Du Ru is the author of a narrative account of his travels that provides one of the first detailed descriptions of the region’s Indigenous religions, cultures, and languages, making him one of the first European authors to write extensively about the lower Mississippi River valley.

Born on October 6, 1666, in Vernon, France, a region of Normandy, Du Ru entered the Jesuit Society in Paris in 1686 and was ordained in 1698. Following Jesuit traditions in education, he taught in the colleges of Quimper, Vannes, and Nevers, after which he took up five years of study in Paris.

In 1699 Du Ru was chosen by Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville to serve as chaplain on his second voyage to the lower Mississippi. The bishop of Quebec, who held jurisdiction over all the land in New France, including the mouth of the Mississippi, was the rightful decision-maker when it came to assigning missionaries and had declared seminary priests, not Jesuits, the missionaries in the region. Despite the bishop’s authority, Iberville believed he had the right to determine which missionaries served on his voyage, and he preferred the Jesuits given their experience as missionaries and talent for Native languages. The Jesuit presence in the lower Mississippi valley resulted in disputes over who was authorized to act as missionaries. These tensions would impact political and religious life throughout the colonial period.

Iberville’s goal was to establish a fort on the Mississippi River and visit Indigenous villages as far north as the Red River. Du Ru traveled with Iberville, recording his experiences. His journal provides a personal account of this five-month expedition from February 1 to May 8, 1700. This compelling narrative suggests a process of cultural translation in which Indigenous peoples and Jesuit missionaries engaged in mutual cultural exchange. While Du Ru’s motive was to gain a better understanding of Indigenous peoples to convert them, these exchanges ultimately had a profound cultural impact on both the Jesuit missionary and Indigenous peoples. The journal remains an important early document of Louisiana history.

Arriving at Fort Maurepas on January 8, 1700, the expedition set out for the Mississippi River, traveling north and making contact with Indigenous groups including the Bayagoulas, Houmas, Tanesas, Natchez, and Colapissas. Du Ru had no prior experience as a missionary. To be successful, it was necessary to learn multiple languages, including the Bayagoula language—Muskogean—as well as Houma, Choctaw, and Chickasaw. His lessons began on the four-month journey from France aboard the Renommé, where Du Ru traveled with a Bayagoula boy, whom Iberville engaged on his first expedition and who taught Du Ru some Muskogean. These lessons provided Du Ru rudimentary knowledge of the language, but better understanding would come when the Bayagoulas provided him a teacher to accompany Iberville’s expedition to teach them their language and customs. Although their talk was initially more by gesture than by words, it was not long before Du Ru’s knowledge of Muskogean was sufficient to produce a rudimentary catechism.

Du Ru’s journal provides daily notes about his education and firsthand impressions of the landscape, people, and their culture, including rituals, healing practices, and religion. He provides richly detailed descriptions of the social and public life of the Bayagoulas and Natchez, including events like the calumet (peace pipe) ceremony, ball games, dancing, feasts, religious rituals, and funerals. Du Ru sought a deep understanding of Indigenous peoples’ worldviews to identify those cultural elements to which Catholicism could be translated. Du Ru attempted to teach the basic tenants of Catholicism in a variety of ways, including baptism, using material culture (rosaries, crosses, images, and texts), and direct teaching through catechism. It is difficult to determine to what degree Indigenous people understood or embraced Catholic religious beliefs. However, by late March 1700, the Bayagoulas, under the direction of Father Du Ru, were building a church that would hold more than four hundred people. This church is claimed to be the first chapel built in Louisiana.

In late 1700 Du Ru, challenged by his lack of success in Christianization, abandoned mission work and returned to Fort Maurepas to join two other Jesuit priests who had arrived to serve at Biloxi and soon after Mobile. Given tensions between the Jesuits and seminary priests over jurisdiction, Du Ru returned to France in 1702 in the hope of reaching a resolution between the two orders but failed to do so, and the Jesuits were recalled to France. He never returned to Louisiana and spent the remainder of his life teaching in France until his death in 1741. His departure marked the end of the first, very brief missionary effort among the Jesuits in the Lower Mississippi Valley. When Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, became governor of Louisiana for the third time from 1718 to 1724, he would be instrumental in the Jesuits regaining a foothold in Louisiana. In addition to the Jesuits, the Capuchins and Ursulines would also arrive as missionaries in New Orleans. The Jesuits remained active as missionaries throughout the Lower and upper Mississippi River valley until their expulsion in 1763.