Taensa Tribe

One of Louisiana's pre-contact indigenous groups

Paul Mellon Collection, National Gallery of Art

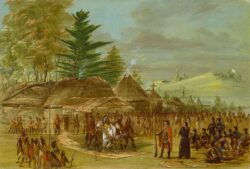

George Catlin, Chief of the Taensa Indians Receiving La Salle. March 20, 1682. Oil on canvas, 1847/1848.

The indigenous Taensa were a mobile and adaptable people who lived in villages in the areas now known as Louisiana, Alabama, and possibly Texas, where they remained a discrete cultural entity into the 1930s. Though the two are sometimes confused, the Taensa people were distinct from the Avoyel–Taensa people of northern Louisiana, who consider themselves affiliated with the southern Hopewell tribes of the Ohio River Valley. Instead, the Taensa people were linguistically and culturally related to the Natchez. While there is speculation that they interacted with explorer Hernando de Soto in 1541, members of the 1682 La Salle Expedition made the first recorded observations about the tribe. Like most native groups living in Louisiana, the Taensa survived initial contact with Europeans and subsequent attrition from disease, slave raiding, tribal consolidation, and warfare.

Tribal Structure and Culture

The Taensa lived in villages governed by a chief, defined their ancestry matrilineally, and lived by farming, hunting, and trading. Henri de Tonti, who served as René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle’s lieutenant on the 1682 expedition, favorably described their village on the banks of the Mississippi River at Lake St. Joseph, in modern-day Tensas Parish. Praising the quality of their “cabins” and temple, Tonti indicated that the buildings consisted of mud-covered walls with cane-thatched roofs and were “adorned with paintings.” He also noted that the Taensa possessed many well-crafted items, including the chief’s finely woven white clothing, a variety of wooden furniture, “delicately worked cane mats,” and distinctive religious figurines made of wood and clay.

Like other groups along the central Mississippi River, the Taensa lived under an authoritarian chief in a hierarchical society. Early descriptions suggest that slaves served the chief and his family. While French missionary François Jolliet de Montigny witnessed human sacrifice among the Taensa, including the sacrifice of infants in a fire when the temple was ignited by lightning, missionary Paul Du Ru wrote about the ritual suicides of family and friends when a chief died: “No chief dies without a dozen of his most loyal friends killing themselves to be buried with him.” After death, the chief’s body was interred in the temple, which housed many small religious figurines along with an eternal flame; access was restricted. Noted for ceremonial devotion, the Taensa made offerings to the small religious objects in the temple.

Though the French described the Taensa as farmers who raised and lived off of corn, there is also evidence that they were involved in extensive trade networks along the Mississippi River. At least some members of the Taensa spoke Mobilian jargon, a pidgin language used by various Native Americans who conducted trade along the river. They were involved in the salt trade. Tonti described the tribe as having items such as exotic feathers and copper plates, acquired through trade. Scholars have also speculated that their frequent moves may have been orchestrated to control vital trade routes.

Tribal Movement

Despite their evident domesticity, the Taensa were known for their ability to move villages quickly and resettle as needed. The reasons for these moves remain difficult to define but seem to indicate a desire to control either food sources or trade routes. Often these migrations brought them into conflict with neighboring tribes. Their village on Lake St. Joseph, for example, apparently was built after 1690 when they had driven out or killed others living on the Ouachita River. Fearing the encroaching Yazoo and Chakchiuma, the Taensa moved again in 1706 at the invitation of the Bayagoula; however, the Taensa then turned on their hosts, killing many and driving the rest away from the area. Around 1719, the Taensa relocated to Bayou Manchac. After the Natchez Revolt changed the diplomatic landscape of Louisiana in 1729, they went to an area north of Mobile Bay, in spite of the fact that the French crown granted the tribe land at the head of Bayou Lafourche on the Mississippi River.

When the Spanish claimed Louisiana in 1762, the colonial government tried to relocate the Taensa farther west, on Spanish lands between the Sabine and Trinity Rivers. There are indications that few if any Taensa actually went; instead, most sought to retain their control over their lands north of Mobile Bay. After Americans gained control of the area around Mobile, however, the remaining Taensa moved to the Red River near the community of Boyce in present-day Rapides Parish and allied with the Apalachee. Both the Taensa and Apalachee sold their holdings in 1803. The Taensa then relocated to Bayou Boeuf in present-day Terrebonne Parish.

In 1812, the Taensa moved to Bayou Tensas near Grand Lake in today’s Cameron Parish. From here, they became closely associated with settlements of the Chitimacha. While their territorial identity began to disappear after 1812, the Taensa language was still spoken within these settlements in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and individuals still distinctly identified themselves as Taensa into the 1930s.

Apparently, the Taensa chose their allies strategically, based on their immediate economic and political needs. While they shared similarities with the Natchez and lived in close proximity to them, they remained hostile to these neighbors. Indeed, they had almost no enduring associations with other groups, choosing instead to make and break alliances as needed. The Taensa pledged their loyalty to the French and then the Spanish, and many converted to Catholicism while living under these regimes. They seem to have largely avoided the English, who raided the Taensa for slaves beginning in the late 1600s.

Tribal Survival and Adaptation

Though never a particularly large tribe, population statistics for the Taensa vary considerably. In 1703 Jean-François Benjamin Dumont de Montigny estimated that there were 300 men and 150 families in the Lake St. Joseph settlement. In 1723, the number of Taensa was recorded on a Chickasaw map at around seventy warriors. A village below Manchac consisting of Taensa, Pacanas, and Mobilians reportedly had a total of thirty gunmen in 1773. It is clear that, like most native Louisiana groups, the Taensa suffered severe population decline after European contact. Scholars indicate that within three generations after La Salle’s appearance, the populations of all native groups on the river plummeted nearly 90 percent.

The Taensa language received attention beginning in the 1880s, when Frenchman Jean Parisot produced a series of documents owned by his grandfather, Haumonté of Plombiéres, that appeared to be written in a distinctive Taensa language. In 1885, however, Daniel G. Brinton wrote a book arguing that the documents were forgeries. American anthropologist and linguist John R. Swanton sided with Brinton in 1908, identifying discrepancies in the forgeries and placing the Taensa language within the Natchesan language group instead, a placement confirmed as recently as 2004 by Ives Goddard of the Smithsonian Institution.