Freeman and Custis Red River Expedition

An American effort to explore the Louisiana Purchase territory was hindered by a log jam on the Red River and two hundred Spanish troops.

Library of Congress

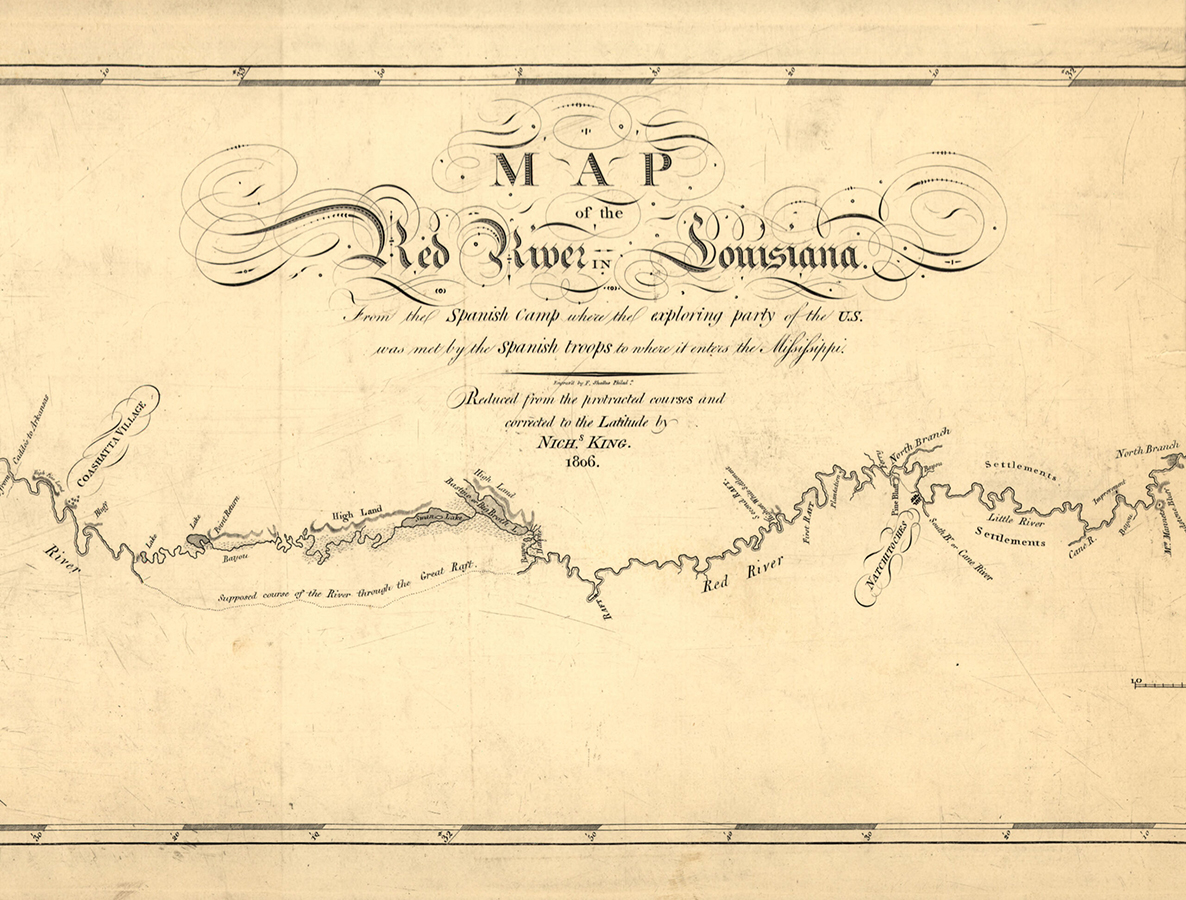

A map of the Red River based on the Freeman-Custis Expedition, 1806.

Beginning and ending in the summer heat of 1806, the Freeman and Custis expedition was an inconclusive American effort to explore the Red River valley, one that faced significant challenges. With a congressional appropriation twice as large as that allocated to the famed expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the Freeman and Custis expedition was the most expensive of the several “voyages of discovery” envisioned by US President Thomas Jefferson to explore the lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. The expedition’s objectives were to 1) strengthen America’s border claims against Spanish Texas by demarcating the purchase territory’s southwestern boundaries; 2) inventory the region’s natural resources; and 3) entice the Caddos and neighboring Native groups away from colonial Spain and into the orbit of American trade and diplomacy.

Sailing Up the Red River

On April 19, surveyor Thomas Freeman and naturalist Peter Custis, charged with finding the source of the Red River, left Fort Adams, Mississippi, with an escort of soldiers led by US Army Captain Richard Sparks. They resupplied and reinforced at Natchitoches one month later and continued their journey upstream with eight boats and a force of fifty men. Throughout June their progress slowed as they navigated around the ancient, 160-mile-long logjam known as the Great Raft by poling and dragging their boats along the shallow bayous on its margins. Reaching the other side after three grueling weeks, they stayed and rested as guests at an Alabama-Coushatta settlement for eighteen days. The occasion prompted nearby Caddos to visit, including the prominent Caddo leader Dehahuit, with whom the Americans felt they made a good impression since he selected several Caddo guides to accompany the expedition upriver. From the American point of view, these weeks spent with the Alabama-Coushatta offered opportunities for conversation and fellowship that served as the basis for the expedition’s primary success, the introduction of American influence to the Caddo communities located deeper in the middle reaches of the river valley.

Spanish Confrontation

Unbeknownst to the Americans at that time—and only discovered decades later by historians rooting around in colonial archives—Sparks’s commander at Fort Adams, General James Wilkinson, was a Spanish agent who routinely sold secret information on American military operations to viceregal authorities in Mexico City. Unwilling to accept the legitimacy of Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase on the grounds that its unspecified hundreds of millions of acres had not even been France’s land to sell in the first place, and further infuriated by the explicit aim of Freeman and Custis to lure away their Caddo allies, the Spanish ordered two hundred troops to march northward from Nacogdoches (in present-day Texas) and prepare an ambush. Led by Captain Francisco Viano, the force dug in above a bend of the Red River a few miles downstream from the present-day boundary of Oklahoma and Arkansas, near New Boston, Texas—a site now known as Spanish Bluff.

After two weeks of muscling their boats from puddle to puddle during the river’s dry season, the Americans found themselves confronting this Spanish force on July 28. Outgunned and under orders to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, Sparks agreed to Viano’s demand that the Americans return to Natchitoches. The two forces peacefully disengaged and camped near each other for a few nights before heading back their respective directions. Freeman and Custis made it back to Mississippi by September, ending their mission.

Aftermath

Aside from successful meetings with Dehahuit and other Caddos, the deliverable results of the expedition included Freeman’s detailed maps of the Great Raft and the channels immediately above it, as well as several hundred pages of notes on the valley’s flora, fauna, and geology. These notes included Custis’s notable identification of the Bois d’Arc tree—also known as the “Osage Orange,” “Hedge Apple,” or “Horse Apple.” The thorny tree with extremely hard, rot-resistant wood and giant green fruits (inedible except to horses and—during the Pleistocene—giant sloths that dispersed its seeds throughout the continent) was once widely distributed across North America but had retreated mostly to the bottomland forests of the Red River Valley by the end of the last Ice Age. Native people in the region had long used Bois d’Arc wood to fashion powerful bows, and the stumps were useful substitutes for stone in building pier-and-beam foundations. Such important “discoveries,” though, were just not as useful or exciting in comparison to those of Lewis and Clark, who had meanwhile returned to St. Louis from their triumphant journey back and forth to the Pacific Coast.

The Red River continued to flummox President Jefferson, who incorrectly insisted that its source lay somewhere in the southern Rocky Mountains based on his friendly speculations with the celebrated biogeographer Alexander von Humboldt. Unknown at the time, the Red River does not start in the mountains at all but, rather, in the high plains in a series of seasonally wet gulleys in northeastern New Mexico. In the immediate wake of Freeman and Custis’s failure to get upriver past the Spanish, Jefferson dispatched Zebulon Pike to find the river’s source by traveling up the Arkansas River and searching for it in the mountain valleys to the southwest during the winter of 1806 and 1807. But Wilkinson also informed the Spanish about Pike’s expedition, and they were prepared to intercept his expedition as well. Moreover, Pike mistook the Rio Grande for the source of the Red River, which made his capture by the Spanish even more convenient. Pike and his men surrendered to Spanish dragoons, who first incarcerated them in Santa Fe and then marched them back through Nueva Vizcaya, Coahuila, and Texas before their repatriation to the United States in the spring of 1808. Eventually a company of the US Fifth Infantry Regiment commanded by Randolph Barnes Marcy located the source of the Red River in 1852, years after Custis, Freeman, Sparks, Pike, Jefferson, Viano, and Wilkinson had all passed away.