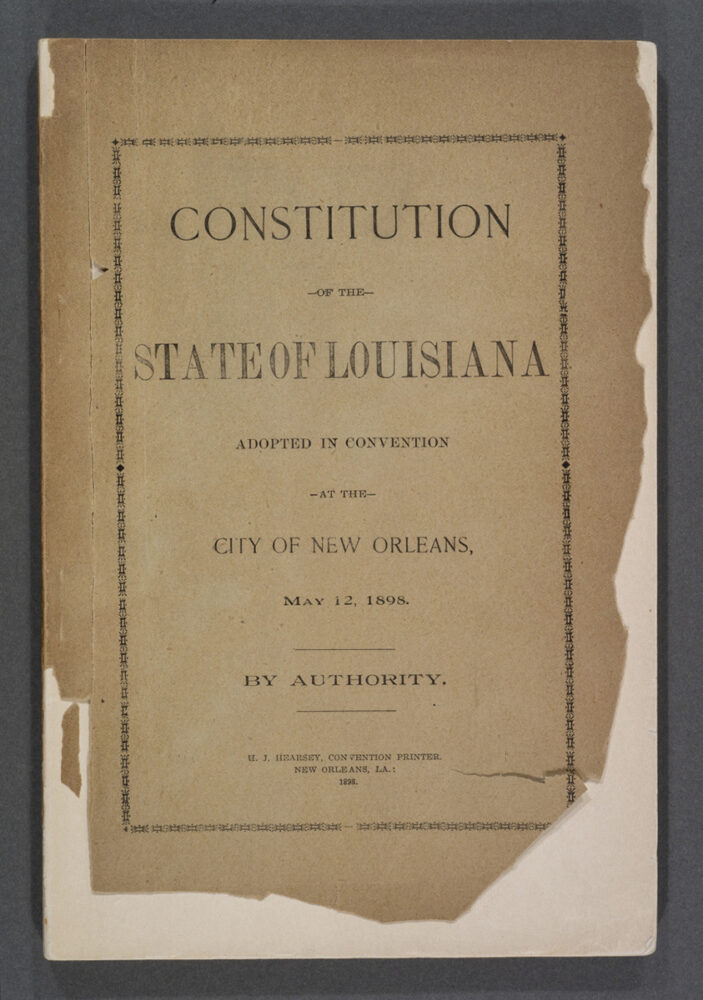

Louisiana Constitution of 1898

Bourbon Democrats suppressed democracy and restored white supremacy in the Louisiana State Constitution of 1898.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

"Constitution of the State of Louisiana," 1898.

In 1896, Bourbon Democrats, also known as Redeemers, an all-white party of former Confederates, called for a constitutional convention for the express purpose of restoring white rule and eliminating any opposition party. Often referred to as the “disfranchisement constitution,” the Constitution of 1898 contained suffrage restrictions (limits on who could vote) that severely diminished the Republican Party in Louisiana, the party that in the nineteenth century supported rights for newly freed, formerly enslaved people. This constitution restricted the voting rights primarily of Black voters but also of disadvantaged white people who had joined the Populist Revolt in the preceding decades. It reduced Black Louisianans to second-class status in every aspect of citizenship, codified existing Jim Crow laws, and paved the way for more. Having achieved a majority through voter intimidation, fraud, and laws put in place during the preceding two years, the Bourbon Democrats sought to codify their lock on power through this constitution, which replaced the Constitution of 1879. Fearing that voters would not approve the new constitution, legislators declared that it would become law without being sent to the voters for ratification. In a symbolic gesture, the convention was held in the Mechanics’ Institute building, the site of the New Orleans massacre of 1866, a Reconstruction-era event when a mob of former Confederate soldiers attacked a peaceful demonstration of Black freedmen during the Republican-led Louisiana Constitutional Convention.

Regaining Power

Following the overthrow of the Republicans during Reconstruction in 1877, Louisiana’s Bourbon Democrats regained power through violence, intimidation, and multiple levels of fraud, including bribery, ballot box stuffing, and “losing” votes cast for Republicans. As the federal government’s interest in supporting voting rights for African Americans in the South waned, Democrats grew bolder in their efforts to reestablish white power. Bourbon Democrats, including Governor Murphy J. Foster, presided over the process of disenfranchising half of the state’s voting-age population and enacting stringent Jim Crow era racial segregation laws, including the Separate Car Act of 1890 that resulted in the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court case.

Foster and other white Louisiana landowners feared that if free and fair elections were allowed, Black people might exact revenge on their former enslavers, despite evidence to the contrary: during Reconstruction, when white elites were temporarily removed from power, Black law makers showed no tendency toward revenge and had been even-handed in their governance. Nonetheless, Foster led the urban and rural white elite to remove any possibility of political power from Black citizens.

Louisiana’s Democrats passed new laws restricting voting rights that disproportionately affected rural, working class, illiterate, and Black people. Due to these new laws, the number of registered voters in Louisiana shrank from 294,432 in 1897, to 87,240 in 1898. Registration for white voters fell from 164,088 to 74,133, and for Black voters, from 130,344 to 12,902. Only after the electorate had been drastically reduced was the referendum on the calling of a constitutional convention put to a vote. The referendum was approved, with 36,178 voting in favor and 7,578 against. Nearly all delegates were Bourbon Democrats, ensuring that suffrage restrictions were an inevitable outcome of the Constitutional Convention of 1898. Thomas Semmes, chair of the Committee on the Judiciary, stated the reason for calling the convention: “We met here to establish the supremacy of the white race, and the white race constitutes the Democratic Party of this State.”

The Constitutional Convention of 1898

Since the Fifteenth Amendment to the US Constitution prohibited removing the right to vote based on race, the convention instituted methods that on their face were race-neutral, but that would disproportionately affect Black citizens. These were:

- An annual poll tax of one dollar for every registered voter, with receipts of two previous years’ payments required before one could cast a ballot.

- A literacy test, administered by the registrar of voters in each parish, with no standards attached, meaning the Democratic registrar determined who passed or failed. This was later expanded into a “constitutional” test so complicated that even lawyers struggled to find the right answers.

- An exceedingly complicated voter registration form that had to be filled out “without assistance”—meaning no illiterate person would be able to do it.

- A property qualification that allowed an adult male to register if he could prove that he owned at least $300 of taxable property (a large amount in 1898). This loophole allowed reasonably well-to-do illiterate white men to register (that is, those who could not pass a literacy test) while preventing landless Black and white men from casting ballots.

- A “grandfather” clause that enfranchised propertyless and illiterate white people. This allowed adult men to register if their father or grandfather was a registered voter in 1867, a time when formerly enslaved people did not have voting rights in Louisiana. The 111 African Americans who registered using the grandfather clause declared that their fathers were white voters. Applicants had three-and-a-half months in which to take advantage of this loophole. After that white people were subjected to the same literacy or property requirements as Black people. The grandfather clause was declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 1915, but it had already served its purpose by then.

In its final moments, the convention delegates voted to base apportionment on total population, meaning that white people in majority-Black parishes gained tremendous power, since the disenfranchised Black population would be counted in the apportionment formula. This would allow men like Governor Foster to retain their disproportionate political power. By prearrangement the convention put the new constitution into effect without subjecting it to a vote of approval by the electorate.

Additional Effects of the 1898 Constitution

The new constitution required everyone to re-register to vote. The number of white voters climbed to 125,437 while the number of voters of color declined to 5,320 by 1900 and fell to an all-time low of 598 in 1922. No Black people were elected to the state legislature again until Ernest “Dutch” Morial won a seat in 1967.

The poll tax depressed voting for disadvantaged men of both races. Even if poor men could afford it, they typically could not take time off work to travel to the courthouse—the only place where one could pay and register—every year. Every obstacle put in front of a voter discourages that person from casting a ballot, as the Bourbon Democrats well knew. Making sure voting day was not a state-wide holiday also prevented working-class people from voting.

With its voter rolls falling by about half overall, Louisiana—along with the entire South—reversed the trend towards greater democracy marching across the rest of the nation. In the South, one-party rule was ensured. The Populist Party was crushed, and the Republican Party all but disappeared—it would not be revived until the 1970s, by which time it was a far more conservative Republican Party than it had been in the nineteenth century.

The Constitution of 1898 also enshrined the non-unanimous jury verdict (Article 36 of Ordinance 365). This allowed the criminal conviction of a defendant by a nine-to-three vote, providing prosecutorial advantage. It was designed to ensure that if any Black people made it onto a jury, white jurors could override the Black jurors. Since people convicted of felonies were stripped of voting rights, this was yet another nail in the coffin of Black enfranchisement. Additionally, because citizens were chosen for jury duty from among the pool of registered voters, Black people would never make it onto a jury because they could no longer pass the stringent registration requirements.

Other noteworthy provisions of this constitution included:

- the creation of the railroad commission (later the public service commission);

- limiting the governor to one term;

- allowing for party primaries—yet another method of disfranchisement, because the Democrats set up theirs as a “whites only” primary in 1904;

- allowing school districts to vote on bond issues for construction of buildings and maintenance of schools;

- phasing out of the convict lease system, although the problem of mass incarceration of African Americans persisted. For most years of the twentieth century, Louisiana had the highest rate of incarceration in the nation.

Black Louisiana’s Response

Louisiana’s Black citizens sued repeatedly to have the disfranchisement provisions declared unconstitutional under the Fifteenth Amendment, but both state courts and the United States Supreme Court, controlled by conservative white men, ruled against them. The Supreme Court had validated Mississippi’s disfranchisement provisions in the case of Williams v. Mississippi (1898), so no similar laws would be struck down, either. For the state’s African American population, the situation grew bleaker than ever. Many subsequently voted with their feet and joined the Great Migration of Black people out of the South in search of better opportunities elsewhere in the country. The state’s Black population began a steady decline.