Newcomb College

Tulane’s coordinate college for women has a strong tradition of its own.

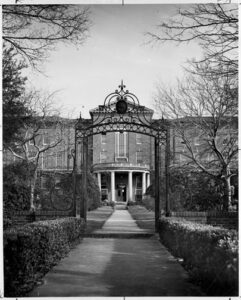

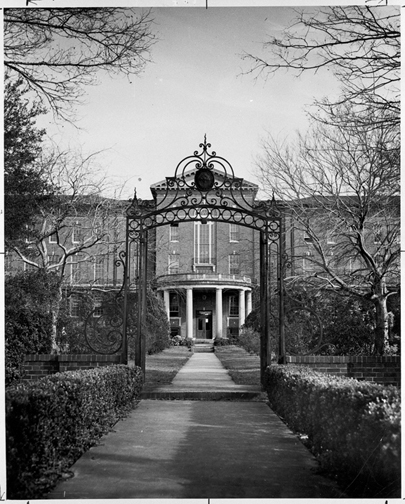

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

A black and white reproduction of a photograph of the exterior of Newcomb College, circa 1949.

Harriott Sophie Newcomb died of diphtheria in 1870 at age fifteen. Her mother, the wealthy widow Josephine Louise Le Monnier Newcomb (1816–1901), spent the next sixteen years in search of a memorial that would render a “useful and enduring benefit to humanity.” In 1886 this memorial wish took form as the “H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College in the Tulane University of Louisiana for the higher education of white girls and women.” Josephine Newcomb’s initial gift of $100,000 to the Administrators of the Tulane Educational Fund created the first degree-granting coordinate college for women in the United States.

Newcomb’s design for the coordinate plan, as a college for white women within a university allowing only white men, called for a separate college president and faculty that had the power to determine policy and curriculum, as though the institution were entirely independent. Brandt V. B. Dixon was hired by university administrators as Newcomb College’s first president and charged with building a viable academic institution. Although Dixon considered Newcomb’s coordinate plan to be an “experiment,” other coordinate colleges for women preceded the founding of Newcomb College, notably Radcliffe College (1879) of Harvard University; and both Girton (1869) and Newnham Colleges (1871) of Cambridge University, UK. Among these institutions, only Newcomb had the power to grant baccalaureate degrees from its founding. Although Dixon admitted he had never visited a women’s college, he was aware of the work at colleges like Mount Holyoke (1837) as well as the work of co-educational institutions such as his own alma mater, Cornell University (1865), which admitted students regardless of race or gender. While nothing indicates he knew anything about the education of Black women even within New Orleans, he certainly held to the rules of segregation. Though many higher education institutions admitted only white students, Newcomb and Tulane were among the few institutions to have such restrictions specified by their founders.

Dixon recruited a talented faculty, percent of whom were white women, and designed a curriculum that paid homage to Josephine Newcomb’s wish that the “education provided should look to the practical side of life as well as to literary excellence.” Dixon introduced several academic “tracks” that would address both the employment needs and academic preparation of the students. The college’s first success came in 1890 with the award of eight baccalaureate degrees and two design degrees.

Campus life first took form on Washington Avenue in New Orleans (1891–1917), where today plaques identify Newcomb’s house and several classroom and dormitory buildings. Within fifteen years of its founding, Newcomb College had achieved the standards required for membership in the Southern Association of College Women. During this time it also gained national recognition for its art school, particularly the Newcomb Pottery produced by students; its physical education program; and its science program. Later recognition came from the continuing prestige of the art school as well as the establishment of the highly regarded Newcomb Nursery School (1926); the Newcomb Junior Year Abroad Program (1954); and the Newcomb Center for Research on Women (1975).

In 1918 the first three buildings purposely designed for the needs of the growing college were built on land adjacent to Tulane University, facing Broadway Street. With the move to Broadway, Newcomb College became less and less an “entirely independent” women’s college. Still, Newcomb students succeeded in the classroom; created their own student organizations; wrote plays and acted both male and female leading roles; produced the Arcade, a literary magazine written and illustrated entirely by students; competed in athletic and academic events with other women’s colleges; and held leadership roles in the Newcomb Senate and as class officers. They also participated in university-wide groups such as the student newspaper and yearbook. From these experiences, Newcomb students came to think of themselves as smart, capable women.

Over time the student body changed, becoming more diverse. Early students had come primarily from white families in New Orleans and from within the state. Steadily the college attracted students from all over the South, then from outside the region. Newcomb had a religious tolerance not present in other women’s colleges, and students were admitted regardless of religion. Then in 1962 the long-overdue integration of Tulane was achieved when university administrators removed “white” from the requirements for admission. Deidre Dumas Labat became the first Black woman to enroll at Newcomb College and graduated in 1968.

Meanwhile the coordinate plan was unravelling. Most undergraduate courses had become co-educational with students “cross-registering” between Newcomb and Tulane Arts & Sciences. A common curriculum was adopted by the two faculties in 1979. Spurred by the perceived inequities felt by the Newcomb and Arts and Sciences faculties, a committee of outside consultants along with a university-led committee recommended the merger of the two faculties. Newcomb alumnae and students organized against the restructuring, as did some faculty. In response, university administrators established the Newcomb Foundation with $2 million in university funds as a mechanism by which the college might gain financial independence.

In 2006, prompted by the devastation to Tulane University caused by the Hurricane Katrina levee breaks, university administrators closed Newcomb College. Again, Newcomb students and alumnae organized. The Future of Newcomb College, Inc. led a five-year legal battle arguing the university’s “renewal plan” violated Josephine Newcomb’s letter of donation, lifetime gifts, and final bequest, which amounted to nearly $4 million. Josephine Newcomb had entrusted university administrators to carry forth her memorial design in perpetuity. The courts found, however, that in naming the university her “universal legatee,” she placed no conditions on the use of her donations. University administrators voted to dedicate approximately $40 million—a sum commensurate with the inflation value of Josephine Newcomb’s gifts, plus funds functioning as the college endowment—to the formation of the Newcomb College Institute. Today, the institute carries on the work of the college with a mission “to develop leaders, discover solutions to intractable gender problems of our time, and provide opportunities for students to experience synergies between curricula, research, and community engagement through close collaboration with faculty.” Newcomb-Tulane College now serves as the coeducational undergraduate division of the University.

Newcomb-educated women have made “enduring benefit(s) to humanity” as Josephine Newcomb wished. New Orleans in particular has benefitted from: activists and volunteers such as Martha Gilmore Robinson, Rosa Keller, Ruthie Jones Frierson, and Anne Milling; city employees and elected officials like Lillie Nairne, Mildred Fossier, Florence Schornstein, Suzanne Haik Terrell; artists Angela Gregory, Caroline Wogan Durieux, Ida Rittenberg Kohlmeyer, Mignon Faget; scientists Ruth Benerito, Willey Glover Denis, Deidre Labat; teachers Sarah Towles Reed, Marion Pfeifer Abramson; writers: Sheila Bosworth, Berthe Amoss; and commentator Gwendolyn Thompkins. Among the college’s most notable alumnae are artist Lynda Benglis; recipient of the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Shirley Ann Grau; US Representative and Ambassador to the Vatican Corinne Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs.