Newcomb Pottery

Influenced by the English Arts and Crafts movement, Newcomb pottery was exhibited around the world, sold in shops nationwide, and written about in art journals throughout the United States and Europe

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

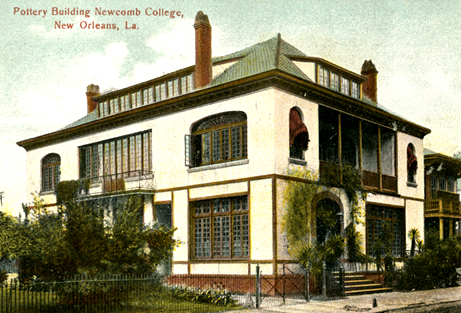

Pottery Building, Newcomb College. Unidentified

Newcomb Pottery is considered one of the most significant American art potteries of the first half of the twentieth century. Influenced by the English Arts and Crafts movement, Newcomb pottery was exhibited around the world, sold in shops nationwide, and written about in art journals throughout the United States and Europe. Newcomb potters (always men) and designers (always women and girls, though called craftsmen) were awarded eight medals at international exhibitions before 1916. Begun in 1895, the pottery operated until 1940. The pottery is highly

The pottery derives its name from H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College, the coordinate women’s college of Tulane University in New Orleans, where the works were cast and decorated as part of the art educational program. The Newcomb art curriculum, as well as the utilitarian philosophy underlying it, were unique among art potteries and women’s colleges of the time. Josephine Louise Newcomb’s gift founding Newcomb College in 1886, as a memorial to her deceased teenage daughter, stressed an education both “practical and literary.” The art department would become the focus of this institutional ideal.

Among the young faculty hired to develop Newcomb’s program of art education was Ellsworth Woodward, who brought with him traditions he learned at the Rhode Island School of Design. Woodward envisioned an ambitious program of vocational training for young women artists. Under his guidance, Mary Given Sheerer was recruited from Cincinnati to teach first china decoration and then pottery. Sheerer became a dedicated leader within the early Newcomb community and a respected authority on ceramics. From 1896 through 1925 most Newcomb Pottery was thrown by Joseph Meyer based on designs prepared by Newcomb students and alumnae under Sheerer’s direction. Completed pots also were decorated by the women in the Newcomb art department. Newcomb Pottery always operated as a studio pottery, never as a large-scale production pottery.

Meyer had been hired in fall 1897 as the third potter for the Newcomb Pottery. His classically shaped pots and consistently high standards provided the background needed for the designs of the Newcomb women. Together they collaborated on a style of pottery with great appeal and artistic merit. Their first success was in the award of a bronze medal at the Paris International Exposition of 1900.

Earlier, Meyer and his friend George Ohr had worked with designers involved in the short-lived New Orleans Art Pottery (1886-1890), some of whose participants became Newcomb students or inspired them. Ohr is said to have worked at Newcomb for a short time in the late 1880s. Biographical information indicates that Ohr left New Orleans in 1890 to return to the Mississippi studio and store he built in 1888. He later became known as the “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” a moniker given for his eccentric personality and his wild and exaggerated pottery pieces that rank among the most experimental works of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Paul Cox was brought to Newcomb Pottery in 1910 to improve the quality of the clay and glazes. Cox developed the soft, waxy, semi-matte glazes that Newcomb Pottery became famous for during its transitional period of production. Cox was with Newcomb Pottery until 1918.

Based on the visions of Sheerer and Woodward, the distinct wares of Newcomb Pottery became well known in the art world of the day. The students and graduates worked with designs evocative of the American South, inspired by Louisiana flora and crafted from local and regional clay. As the twentieth century opened before them, some students moved toward developing more modern designs, yet still maintained the philosophy that no two pieces of pottery should be alike. During its nearly fifty years of operation, Newcomb Pottery provided employment to roughly ninety Newcomb graduates, and produced some seventy thousand distinct pieces of work.

Although Newcomb pottery is best known for its blue and green, several other colors can be found as well. The early works reflect an interest in earth tones such as olive greens and yellows, though in general, the period 1895-1900 was marked by experimentation with a variety of clay bodies, glazes, and colors. During 1910-1918, a transparent matte glaze over blue and green underglazes was frequently used. In the period 1918-1928 pink sometimes was added to these blue and green tints. From 1928-1934, a strong cobalt blue with green was added; and in 1935-1940, blues, soft pinks, and greens of different shades appeared. Decorative motifs often drew from southern flora, ranging from pinecones and cotton bolls to moss-draped cypress trees and garden flowers such as daffodils and irises.

Newcomb Pottery was sold through exhibitions and displays. In addition, the college advertised its wares in The Newcomb Arcade, the college magazine (published 1909-1934), and, from 1898 onward, through consignment to various stores, shops, and organizations around the country. Family records show that the first piece of pottery was sold in 1896 for $4.00 by Selina Bres (later the mother of sculptor Angela Gregory) to a Mrs. Bickham in Boston. Newspaper records in 1901 indicate “a lamp was … sent to Berlin, and … to Connecticut.” By this time, Ellsworth Woodward noted that young women could make a modest income from their own work. Soon, Woodward was able to convince the college administration to put up funds for the construction of a separate pottery building, which included a spacious sales room. New Orleans newspapers regularly reported on the pottery’s commercial success.

In the January 1909 edition of the Arcade, Woodward wrote: “Schools have come to realize that where one may be prepared to add to the sum of beauty and achieve personal success through the pictorial arts, a hundred may be trained to useful enterprise in the field of artistic craftsmanship—a limitless field in which the world of industry ministers to the needs of a refined civilization.”

This essay was adapted from an online exhibit of Newcomb Pottery researched, designed, and produced by Veronica Leandrez, Crystal Kile, Lisa Pollack, and Susan Tucker.