Port of Lake Charles

The Port of Lake Charles opened in 1926 and remains one of the country’s most active oil, gas, and petrochemical transportation hubs.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

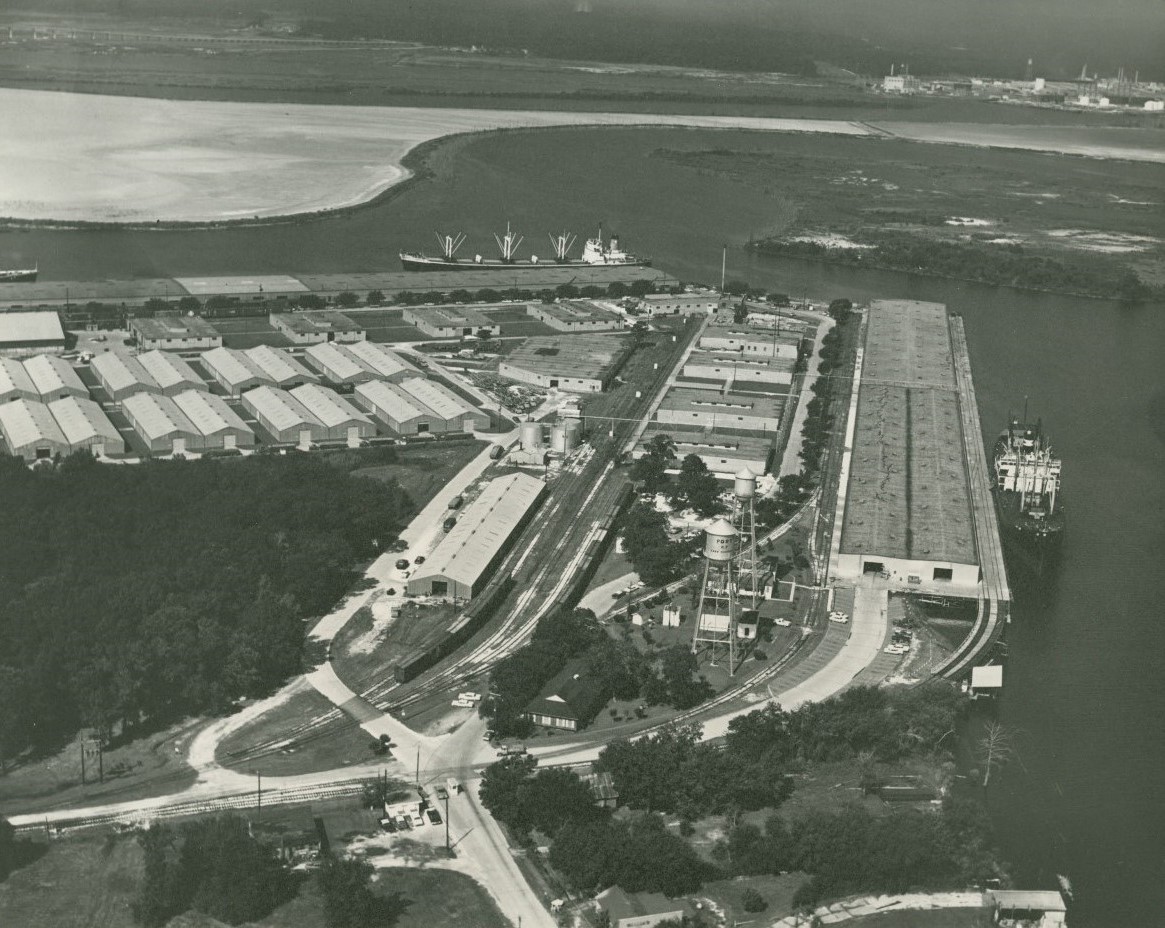

Arial view of the Port of Lake Charles in Port Charles, Louisiana, looking west.

The Port of Lake Charles, a political subdivision of the larger Lake Charles Harbor and Terminal District, manages more than two hundred square miles of land in southwestern Louisiana. Its holdings include a direct-to-Gulf waterway known as the Calcasieu Ship Channel and miles of industrial waterfront property. Much of this waterfront property is leased to petrochemical–related businesses, including state-of-the-art liquified natural gas plants whose products are efficiently transferred to ocean-going tankers at the port and channel. Such immense transfers of transportable energy made the port and channel part of the “critical energy corridor” on the Gulf Coast that is vital to the American economy. Beyond petroleum products the port boasts a historical record of trade in lumber and rice, and according to a 2020 economic study by Martin Associates, it ranks as one of the highest in terms of economic output. However, industrial development near the port has led to pollution, increased saltwater intrusion, and coastal land loss.

What is now one of the nation’s premier ports, reportedly providing $29.9 billion in marine cargo activity in 2020 alone, once began as a dream to early maritime and lumber interests in the southwestern region of Louisiana in the 1880s. Emerging from the Civil War, many business interests looked to the South to promote national reunification through economic development. As early as the 1880s, marine and lumber interests in eastern Texas and western Louisiana pushed to open up what was then a shallow pass at the mouth of Calcasieu Lake, a large brackish water body in Cameron Parish. Only during high tide could ships cross the pass and traverse the lake to where the mouth of the Calcasieu River drains and the city of Lake Charles sits. It was daunting for large ships with deep drafts to make it through the shallow lake to the port, severely limiting commerce. An Army Corps of Engineers report in 1907 called for dredging a ship channel as early as 1908, but it was not completed until the 1930s.

The start of the twentieth century saw renewed motivation for improving inland waterways. The idea of connecting Gulf Coast waterways to the East Coast surfaced in the 1870s. Still, it was the growth of the lumber industry, followed by petroleum interests in the wake of the 1901 Spindletop, Texas, oil discovery, that drove the need for expanding the inland waterway system. A portion of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, as it is now known, was completed in 1913 and 1914, connecting Sabine Pass through the Sabine River to the railroad terminals at Lake Charles. Lake Charles benefitted immensely from rail and water connections and a special act of the state legislature passed in 1924 that created the Lake Charles Harbor and Terminal District to manage development at the Port of Lake Charles. The district was administered by a five-person board of commissioners that organized projects to deepen and widen various canals connecting to the port. The port officially opened in November 1926, and trade exponentially increased over the next decade.

As the importance of trade at the Port of Lake Charles increased, so did the need to connect the port directly to the Gulf of Mexico. By the 1930s mariners trading at the port still made the circuitous journey through the canal to the Sabine River into Sabine Lake and out into the Gulf of Mexico. Through the efforts of politicians such as US Rep. Rene DeRouen and US Sen. John H. Overton, Congress appropriated funding in 1938 to dredge a deep ship channel from the mouth of the Calcasieu River to the Gulf. The start of World War II and the need for petroleum products fast-tracked the construction of the channel, which opened in 1941.

The Port of Lake Charles now stands as one of the nation’s busiest ports, with eighty years of development directly tied to petrochemical industries. However, increased salinity from dredging the channel and industrial pollution within the waterway system have contributed to environmental degradation, including coastal land loss. By connecting the Calcasieu River to the Sabine estuary and the waters of the Gulf, saltwater invaded tidally affected areas of southwest Louisiana. By 1945 rice growers in the region complained that the dredging and deepening of the Calcasieu Ship Channel and the interrelated waterways led to greater saltwater encroachment. Many locals predicted increased salinity changes in the low-lying region as the port and its waterways expanded in the postwar decades. This prediction proved prescient, as observers have noted that southwest Louisiana experiences a severe, man-made land-loss crisis.

Recent experiences with major storms like Hurricanes Laura and Delta in 2020 point toward extended periods of inundation by storm-driven saltwater as the major culprit in coastal land loss in the region. While tradeoffs were made in the past at the expense of environmental protection, the liquid natural gas industry’s growth at the port supplies a continued need and vital source of funding for flood protection and coastal restoration.