Protestantism in Louisiana

Several Protestant denominations are present in Louisiana with Southern Baptist and Methodist as the most dominant.

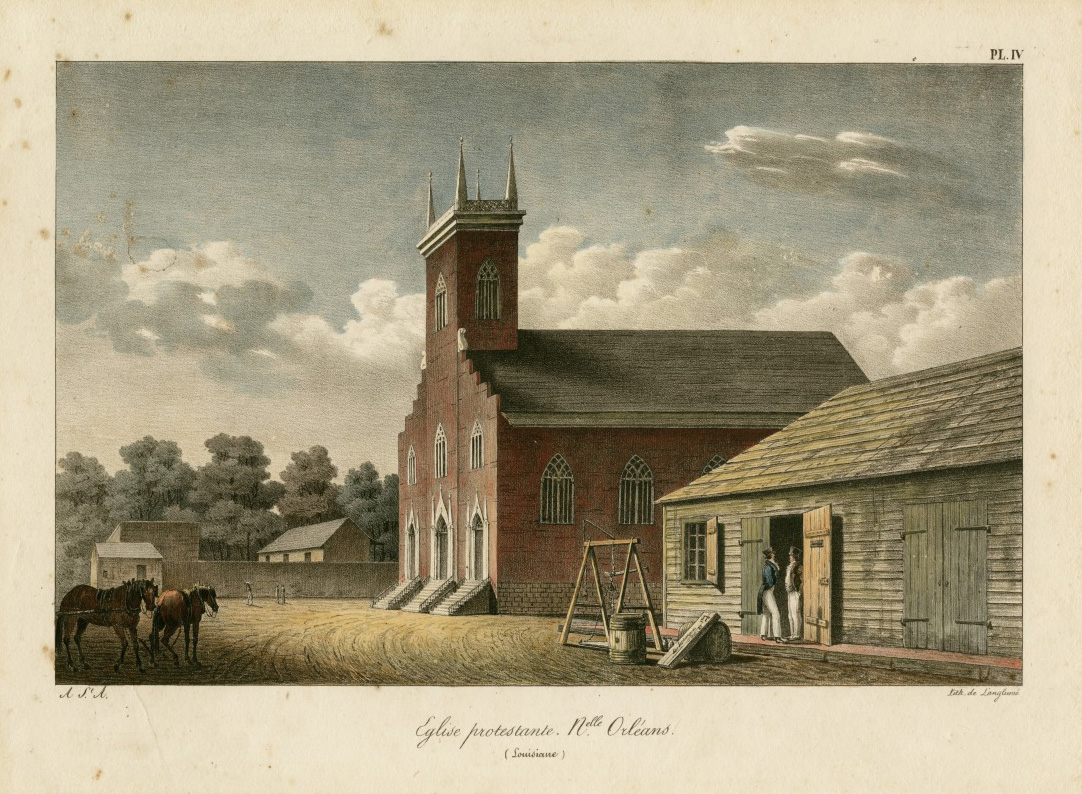

The Historic New Orleans Collection

1821 view of the Congregational Church, New Orleans's second Protestant church, by Felix Achille de Beaupoil.

“Protestantism” is an umbrella term describing a variety of Christian denominations that separated from the Catholic Church because of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. Several Protestant denominations are present in Louisiana. The two most dominant are Southern Baptist and Methodist, which are popular among Black and white Louisianans.

Origins of Protestantism

The Protestant Reformation was a religious revolution that began in Europe in 1517 when a German monk, Martin Luther, launched a crusade against the Roman Catholic Church. Along with corruption charges, Luther contested major points of Catholic theology and doctrine, in particular the notion that the Catholic hierarchy was the means to grace and salvation. Instead, he postulated “a priesthood of all believers” not defined by allegiance to Rome. The Catholic Church branded Luther a heretic and excommunicated him. His followers, protected by powerful monarchs in northern Europe, left Catholicism and established the Lutheran Church. The Lutheran challenge spawned more religious protests and divisions across Europe. Among these were dozens of Anabaptist sects that criticized the baptism of infants as unbiblical. Anabaptists helped lay the foundations for today’s modern Southern Baptists.

Some countries, such as England, instead defied the Roman Catholic Pope’s authority for political reasons. King Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church and established a new Christian denomination, the Church of England (often referred to as the Anglican Church), in 1534. Today’s modern Episcopalians are the Anglican Church’s religious descendants.

Other religious leaders quickly emerged to challenge the Lutheran, Anglican, and Catholic Churches. Followers of the French theologian Jean Calvin established competing Protestant sects that formed the forerunners of today’s Baptists, Presbyterians, and Puritans. John Knox led the establishment of the Church of Scotland in 1560, the beginnings of today’s Presbyterians.

Since there was no concept of separation of church and state at the time, and each political unit had only one sanctioned religion, religious dissenters faced persecution from Catholics and Protestants alike. Dissenters fled to the British colonies in North America for refuge.

Rifts within Anglicanism gave birth to Puritanism and Methodism. While Congregationalists predominated in New England and Anglicanism predominated in the Chesapeake area, Methodism gained a strong foothold in the southern colonies of America thanks to the missionary efforts of founders John and Charles Wesley and their foremost missionary in America, Frances Asbury.

Origins of Methodism

Methodism was founded in England in the early eighteenth century by brothers John and Charles Wesley, ordained Anglican priests who developed innovative theologies about God’s grace and salvation that were distinctive from the Church of England. The Wesleys began touring the colony of Georgia in 1735 and gained converts through “circuit riders,” or preachers who reached remote areas on horseback to preach at small, upstart churches.

Americanization of Protestantism

With the success of the War of Independence, all Protestant denominations in the United States severed ties with Europe and established American churches with leadership based on this side of the Atlantic. Anglicans in the United States formed the Episcopal Church. In 1784 a meeting in Boston established the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC), which had about eighteen thousand members in America.

Baptist Origins

Unlike Methodists, who can trace their religious heritage to a pair of brothers, Baptists have a more diffuse and contested origin. Due to their decentralized governing structure, which gives most authority to local congregations, Baptists can differ in how they worship and in their doctrines. Baptists share a rejection of infant baptism and accept baptism only by believing adults through full immersion. Since they were often a persecuted minority in Europe, Baptists developed a strong adherence to the concept of separation of church and state. The first Baptist congregation in North America was established by Roger Williams in Rhode Island, which was also the first colony to enact complete religious toleration and total separation of church and state in its 1663 charter, granted by King Charles II following the restoration of royal rule in England.

Louisiana’s Colonial Religious Heritage

Colonial Louisiana was officially Catholic because the monarchs of France and Spain remained loyal to the Papacy. Yet in areas east of the Mississippi River—in the Florida Parishes—English-speaking Protestants settled land and opened trade ties to New Orleans. Their numbers were small, however, until after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Louisiana Statehood and Protestant Expansion

When Louisiana became an American territory, the US Constitution—with its First Amendment guarantee of freedom of religion—became the law of the land. Hence, Protestant and Catholic churches and cultural practices were tolerated. With assurance they could practice their religion as they saw fit, English-speaking settlers poured into the territory from the former English colonies, bringing their faith traditions with them.

While Methodists predominated among Protestants in Louisiana throughout most of the nineteenth century, by 1890, Baptists outnumbered Methodists, a situation that has not changed since. The first Baptist church was founded in Louisiana in 1812 by a freed enslaved person named Joseph Willis. According to authors Thomas S. Kidd and Barry Hankins, Willis’s color made him subject to “strong prejudice,” and he was often “threatened with violence.” He nonetheless established several Baptist congregations and became the first moderator of the Louisiana Baptist Association. Baptists stress the self-governance of congregations, associations, and conventions, which helps explain their large numbers: When portions of the congregation fell into disagreement with each other, it was easy to split off and establish another church more to their liking. This, in turn, has produced many varieties of Baptists, but they all share the same emphasis on individual (rather than societal) salvation. Baptists’ focus tends to be on the next (other-worldly) life rather than this life—a major difference from the other main Protestant denomination in Louisiana, Methodist. Inspired by the Great Commission—“Go ye therefore and teach all nations, baptizing them; [and] teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19–20)—Baptist and Methodist evangelists traveled along the frontier of settlement, establishing congregations and gaining both Black and white adherents as the population expanded throughout the state.

Black Protestants

Though Christianity was imposed on them by their enslavers, some Black people embraced it and blended it with their own African-descended traditions, such as the interactive call-and-response pattern between preachers and congregations. For many enslaved people, Christianity offered a message of hope, a happier existence in the heavenly kingdom—a reward for their suffering here on earth—and the promise of divine justice, which, in their view, would be exacted upon the white people who oppressed them. Many Black people could identify with the tragic figure of Jesus, who, like them, suffered and died at the hands of political tyrants but whose reward was spiritual redemption and everlasting life.

Slavery, Emancipation, and Segregation in Louisiana’s Protestant Churches

During the nineteenth century, Protestant churches and congregations throughout the state and nation split from one another over the church’s stance on slavery and white supremacy. White southern Baptist apologists joined other southern Protestant ministers in developing biblical defenses of slavery and of white supremacy. In 1845 white Baptists formed the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). Emphasizing individual conversion and personal morality, white southern Baptists chose to ignore slavery and racism. The SBC saw enormous growth while perpetuating the prevailing mores of white supremacy.

Following the Civil War and emancipation, eager to exercise autonomy, formerly enslaved people departed white churches and organized their own. Northern Protestant denominations, under the umbrella of the American Missionary Association, sent missionaries to Louisiana to educate formerly enslaved people and assist in building churches. In many cases the church building served as a school and a social center. With the assistance of the Freedmen’s Bureau, Northern aid societies also established Black colleges in Louisiana, including Straight University, New Orleans University, and Leland University.

For many Black people the church offered a literal and figurative sanctuary, and it became the organizational center of the Black community. During the mid-twentieth century, several Black clergymen became prominent civil rights leaders, such as Rev. T. J. Jemison from Baton Rouge. In addition, Black evangelical churches were important in developing Black culture. Among other things, they facilitated the development of Black Gospel music.

Unlike Methodists and Presbyterians, who also split before the Civil War over the issue of slavery, the main denominations of Baptists in North and South have not reunited. The Louisiana Baptist Convention, an affiliate of the SBC, formed in 1848 in Bienville Parish. In 2023 it represented about 620,000 members. Black Baptists formed the National Baptist Convention in 1895. The largest national Black Baptist denomination, with 8.4 million members nationwide, the National Baptist Convention had 118 congregations in Louisiana in 2020, representing about sixty-two thousand members.

Baptist faith and practices appealed to Black Louisianans before slavery ended and afterward. Put off by the excessive intellectualism, formality, and adherence to Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and Lutheran liturgy (denominations that expended almost no energy proselytizing among them), many Black people flocked to the Baptist fold. They liked the spontaneous form of worship, its simplicity, informality, joyous bodily movement, hand clapping, full-throated singing, and fiery preaching styles—all of which easily fit into traditional African forms of worship.

Theological and Political Differences

White and Black Baptists tended toward conservatism in both politics and doctrine, although this meant different things depending on the believer’s race. Eschewing social justice, white Baptists founded institutions originally to serve only their co-religionists rather than the general populace. These institutions included orphanages, hospitals (such as Ochsner Baptist in New Orleans), private schools, and an institution of higher learning, Louisiana Christian University in Pineville. Opposed to racial integration, white Baptist churches established what were referred to as segregation academies that denied the enrollment of non-white children on their grounds in the 1960s. These schools folded (or consolidated) as the state expanded its services and the federal government no longer permitted private schools or any other institution to discriminate based on color.

While Black Baptists supported the Black Freedom Movement, they tended to oppose liberal religious reforms such as expanding the role of women and LGBTQ+ members in church structures and governance.

Like other southern Protestants, white southern Methodists broke with their northern counterparts over the issue of slavery. Rather than condemning slavery southerners defended it and issued biblical and theological justifications of slavery. In 1844 white southerners seceded from the MEC to form the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MECS). This divide continued until 1939, when, after years of unification talks stalled over the issue of racial integration, the MEC, MECS, and Methodist Protestants merged to form the Methodist Church.

Methodists stress “good works” as well as faith, which has attracted them to social reform movements and led them to create benevolent institutions such as the Salvation Army and Goodwill Industries. Male and female Methodist missionaries proselytized among immigrant and other ethnic populations both abroad (such as in Korea, Japan, and China) and at home, where they established churches and community centers among Native Americans and in immigrant and Black neighborhoods. Methodists’ commitment to Christian higher education resulted in the establishment of many schools and seminaries throughout the South. In Louisiana, Centenary College is the premier Methodist institution of higher learning.

In the twentieth century Louisiana Methodists participated in Social Gospel activities and causes, such as advocating for better pay and improved working conditions for working-class people, an end to child labor, and an expanded social welfare state. Methodist women were more active than Protestant men of any variety in engaging in social justice reform. These efforts are designed to break down institutional barriers that prevent people from being able to live what Jesus referred to as “abundant life,” or a life not plagued by systemic oppression, a life where all people can work to transform the world into a more equitable place. Methodist women built and maintained schools and other institutions for poor and marginalized communities such as immigrants and Black people, and they lobbied elected representatives, asking them to be fair and equitable in the distribution of services to people of all ethnicities.

Another merger with the Evangelical United Brethren in 1968 created the United Methodist Church (UMC). As part of the negotiation agreements, Methodists agreed to end racial segregation in the UMC, which in turn caused considerable “white flight.” Methodist numbers in Louisiana shrank as many white members left to join more conservative denominations. As of 2019 UMC membership in Louisiana totaled about 109,000.

The UMC splintered again over the issue of same-sex marriage and openly LGBTQ+ clergy. A special General Conference held in 2019 made it possible for congregations that are opposed to same-sex marriage and the ordination of gay clergy to remove themselves from the denomination (or disaffiliate) and keep their property after fulfilling certain financial obligations. As of May 2023, ninety-five churches in Louisiana voted to disaffiliate, the vast majority being white congregations.

At the 2024 General Conference, delegates voted to remove discriminatory language and bans from the Book of Discipline related to “self-avowed practicing” gay and lesbian people. It removed a ban on LGBTQ+ ordination, on performing same-sex weddings, and removed a prohibition against using church funds to support groups, activities, and causes that promote the acceptance of homosexuality. Now it states the opposite, that church funds cannot go to anything that rejects LGBTQ+ persons. Delegates also voted to approve regionalization, a new organizational model that allows each geographic region of the global UMC to adopt rules for its own conference, thus creating space for differences of opinion on this and other controversial positions.

Black Methodist Churches

The Methodist Episcopal Church had remarkable success during Reconstruction in gaining Black church members, more than any other northern-based denomination. However, Black Methodists always worshiped in separate congregations. Two northern-based Black Methodist denominations also established congregations in the state: the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion (AME Zion). Of those, the AME had a larger population. Other Black Methodists joined the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CME—later renamed the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church), formed in 1870, which collaborated with the white MECS for additional resources and teaching assistance.

Holiness and Pentecostal Churches

In the twentieth century, many Black people joined the Holiness and Pentecostal churches, which emphasized healing and release from burdens and the ecstatic dimensions of worship. The editors of the New Historical Atlas of Religion in America explained that music and dance in Black worship services “link the spirit of the old spirituals, blues, and jazz with the drums and tambourines of Pentecostal worship” and thus helped to preserve and strengthen Black musical traditions. The two largest Pentecostal denominations have divided along racial lines: The Assemblies of God is nearly exclusively white, and the Church of God in Christ is primarily Black.

Conclusion

In addition to the denominations discussed above, there are a small number of other Protestants represented in Louisiana, too, such as Christian Scientists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (otherwise known as Mormons). The percentage of the population identifying as Christian has fallen steadily since 1970, while the percentage of those who identify with no religion has climbed. Denominations experiencing numerical growth are Pentecostal and/or Evangelical. In addition, independent Christian congregations that have no denominational affiliation (so-called megachurches) are increasingly popular among millennials.