Slavery in Spanish Colonial Louisiana

During Louisiana's Spanish colonial period, the number of enslaved Africans and the number of free people of color increased greatly.

Louisiana State Museum

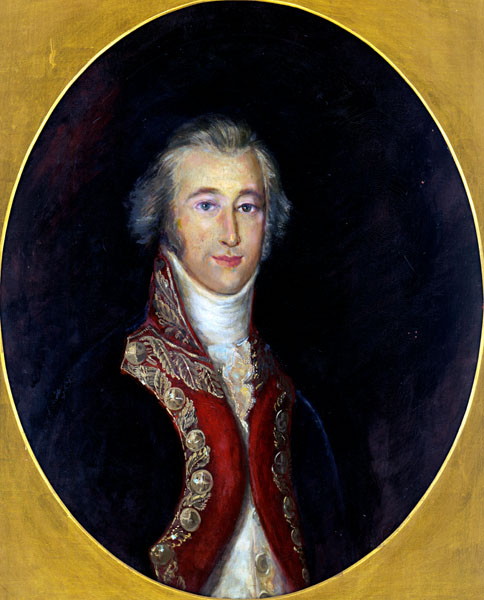

General Alejandro O'Reilly, shown here in a portrait by Aurora Lazcano, was the second governor of Spanish Louisiana.

As a result of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the French and Indian War, France surrendered most of Louisiana, including New Orleans, to Spain. Under Spanish rule, Louisiana became a more developed, successful colony, in large part because of a sizable increase in the enslaved population. The Spanish period can be seen as transitional, linking the “society with slaves” of the French period to the mature “slave society” that emerged under later American rule. During the Spanish regime, the total population of Louisiana increased from 10,000 to 30,000, and the enslaved population likewise increased from 4,500 to nearly 13,000. Moreover, the reopening of the African slave trade both “re-Africanized” Louisiana’s enslaved population and contributed more ethnically and culturally diverse peoples, because the slave traders imported from different geographical regions of Africa.

Spanish Changes to Slavery Laws

One of the decisive actions that Governor Alejandro O’Reilly took when he came to consolidate Spanish control over Louisiana in 1769 was to ban the trade in enslaved Native Americans because it was creating unrest, as various tribes raided each other for captives they could sell. However, proclamations issued by officials in Europe and delivered by their representatives in colonial capitals were often ignored in the hinterlands. Traders along the former French-Spanish border continued to sell captive Native Americans for a number of years. When Governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró republished the decree in 1787 and allowed enslaved Indians to sue for their freedom in court—usually successfully—slave owners presumably lost interest in purchasing contraband natives.

Although slavery was an inherently inhumane institution, Spanish law regarding slavery differed from the French Code Noir in ways that somewhat improved the lives of those living in slavery. The Roman Catholicism of the Spanish acknowledged, at least on paper, that enslaved individuals had souls and were thus the spiritual equals of the people who owned them. Under Spanish law, enslaved people were allowed a few more privileges and protections than the French had granted; in reality, Spanish slave owners violated most of these rights, though in some cases they were upheld. In particular, Spanish slave law recognized coartación, the right of self-purchase, and although most enslaved people had no chance of capitalizing on this privilege, a significant number did. Moreover, manumission was a well-developed tradition under the Spanish system of slavery, and many enslaved individuals were freed. Despite such efforts of the Spanish crown to liberalize slavery, however, the lives of enslaved people in Louisiana remained harsh. Nonetheless, the Spanish slave regime exhibited a degree of openness greater than that which preceded or followed it.

Under the previous French regime, manumission of enslaved people was relatively rare. The slave owner had to make the request in person before the Superior Council and navigate a number of additional bureaucratic barriers. However, enslaved people were allowed to earn wages for themselves during times when their owners did not require their labor. The owners received a portion of the earnings, and the enslaved person kept the rest for personal use. During off-hours, enslaved people were allowed to procure extra food for themselves through hunting, fishing, and gardening, and they were permitted to market their skills; enslaved people could even sell their surpluses and handicrafts. These arrangements gave the people held in bondage a small measure of autonomy while sparing their owners a considerable amount of money. The two fires that ravaged New Orleans in 1788 and 1794 increased the capital enslaved people could accumulate for their self-manumission; the Spanish crown invested heavily to rebuild the city, and much of the money was used to pay enslaved workers for their reconstruction skills. Some enslaved laborers were then able to take advantage of coartación: if an enslaved person asked his or her owner to set a price for self-purchase, the person’s owner was required by law to name a fair market price and free him or her when he or she could pay it.

Throughout the Spanish period, the wealthier Creole planters argued about what they interpreted as the leniency of Spanish slave laws, citing enslaved people’s right of self-purchase as one of the system’s worst elements. The growing number of gens de couleur libres (free people of color) did in fact serve to counter the power of the French Creole elites somewhat. The free Black population experienced a dramatic increase during the Spanish era, from fewer than one hundred at the end of French rule to fifteen hundred free people of color by 1800. While the number of people held in slavery more than doubled during this period, the population of libres, as the freed people were often called, grew by a factor of sixteen. The libres established themselves as artisans and tavern keepers and in a few cases even as slave owners. Spanish colonial authorities generally envisioned a three-tiered society that included white, free Black, and enslaved people, whereas the French and Anglo-American vision included mainly free whites and enslaved African-descended people, with a very small number of libres. The Spanish tradition saw free Black people as a legitimate, integral part of society: by offering enslaved people an opportunity to attain freedom through submission and hard work, the Spanish hoped to avoid violent insurrections.

One of the avenues of opportunity that the Spanish colonial system threw open to free men of color was service in the local militia. The Spanish in Cuba had enrolled free Black men in militias for more than seventy-five years when Governor Bernardo de Gálvez organized libres into two militia companies to defend New Orleans during the American Revolution. They fought in the 1779 battle in which Spain took Baton Rouge from the British. Gálvez went a step further for his campaigns against the British outposts in Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida: he recruited enslaved men for the militia by pledging to free anyone who was seriously wounded and promised to secure a low price for coartación for those who received lesser wounds. During the 1790s, wars and political upheavals in Europe and the Americas prompted Governor Francisco Luis Héctor, barón de Carondelet to beef up local fortifications and recruit even more libres for the militia. Carondelet in fact doubled the number of free men of color who served, creating two more militia companies—one made up of moreno (Black) members and the other pardo (mixed race). Serving in the militia brought libres one step closer to equality with whites, allowing them, for example, the right to carry arms and boosting their earning power. These privileges distanced libres further from enslaved Black men and women and encouraged them to identify with whites. For their part, the white authorities in the colony gave the moreno and pardo militia companies the worst duties, such as repairing levee breaks or venturing into the swamps to root out enslaved people who had run away.

Maroon Communities

Among the most widespread forms of resistance to slavery in colonial Louisiana was marronage, living in the wilderness as a runaway. If an owner was unreasonable or an overseer vicious, enslaved people sometimes took refuge for a period of days or weeks—and sometimes permanently—in the cypress swamps that surrounded New Orleans. Enslaved laborers who had to fell and haul cypress trees out of the swamp to lumber mills learned their way through the maze of wildlife trails and narrow waterways, so when they ran away, they built shelters in the remotest areas. Marronage had begun on a small but worrisome scale during the French colonial period, and by the time the Spanish took over Louisiana, maroon settlements included as few as a handful of runaways to as many as several dozen, including entire families. Over time, the maroon groups developed self-sustaining communities, creating their own networks of trade and exchange. Maroons also raided nearby plantations to obtain food and other supplies. Although the local enslaved populations generally sympathized with the maroons, tensions also arose between the two groups, since enslaved people who remained with their owners were punished for harboring or provisioning maroons. The leader of maroon society was said to be Juan San Malo, a shadowy figure who evaded and fought off Spanish authorities for several years before being captured and executed in the mid-1780s. San Malo, whose memory was kept alive in songs and stories, thereafter came to symbolize collective resistance for people enslaved in Louisiana.

New Crops and Revolutionary Ideas

The 1790s witnessed two developments that profoundly shaped slavery in Louisiana as well as the colony as a whole. The first was the successful production of granulated sugar from sugarcane. The advent of commercial sugar production resulted from the decline of tobacco and indigo and as a consequence of the slave revolt in the largest sugar-producing French Caribbean colony, St. Domingue (today’s Haiti). The revolt essentially removed St. Domingue from the world sugar market, and it led to an influx of planters, sugar makers (many of whom were free men of color), and enslaved men and women familiar with sugar culture from that colony to Louisiana. The second development occurred in the southern United States with the invention of the cotton gin, which revolutionized cotton production. In the following decades, the plantation revolution spread throughout Louisiana, with sugar dominating in the southeast and cotton virtually everywhere else. If the fate of slavery had ever been in doubt before the 1790s, the emergence of sugar and cotton as major cash crops settled the question.

The years of Spanish rule coincided with what has been called the Age of the Democratic Revolution, which swept the Western world during the late eighteenth century and challenged slave regimes everywhere. Although the North American slave societies withstood the threat, the revolutionary impulse enabled enslaved individuals to gain freedom and allowed enslaved populations greater autonomy within the slave system. The 1768 insurrection of Louisiana colonists against Spanish governance (which was not a democratic revolution but an attempt to restore French rule) convinced planters that Spanish officials had to assert their authority firmly: they feared that an unstable government might invite a slave revolt. The American Revolution caused many Loyalist slaveholders to seek refuge in West Florida. The French Revolution (1789–1799) and its offshoot, the slave revolt in St. Domingue (1791–1804), also led large numbers of slaveholders to flee with their human property to Louisiana. The ideology of the French Revolution resonated in Louisiana, and many planters initially embraced it, mostly as an expression of their continuing discontent with Spanish rule. However, they came to fear that radical ideas from the French and St. Dominguan revolutions about freedom and equality could “infect” the minds of people they owned, so they eventually endorsed Spanish efforts to suppress revolutionary thought. Faced with the influx of enslaved people who had directly experienced revolution, as well as with the general threat to slavery that the Age of the Democratic Revolution presented, Spanish colonial authorities clamped down ruthlessly on perceived threats to the regime and blocked crown attempts to liberalize slavery.

In fact, revolutionary sentiment did contribute to organized slave resistance. Enslaved people had resisted in whatever ways they could from the beginning, but the increased population in bondage, along with the consolidation of the slave regime, sparked greater opposition. The largest effort at rebellion during the Spanish period was the Pointe Coupée conspiracy, which took place in 1795, soon after the French Revolution had reached its bloodthirsty peak and while slave revolts racked Guyana, Venezuela, and Jamaica. The Louisiana planters discovered the Pointe Coupée revolt while it was still in the planning stage. Sixty people were convicted as conspirators; twenty-three of them were executed by hanging, and their heads were placed on pikes along the river road between Pointe Coupée and New Orleans as a warning against further plotting. Governor Carondelet, who had previously sought to uphold Spanish slave law over the objections of the Creoles who dominated the Cabildo (the administrative seat of the Spanish crown), began making more concessions to the wealthy landowners.

In 1803, when Louisiana was restored to France for less than two weeks before the territory was transferred to the United States, the elite Creole planters insisted that Pierre-Clément Laussat, the French official in charge, put the stricter 1724 Code Noir back into effect. Three years later, planters serving in the new US territorial legislature managed to pass even more punishing measures, undoing much of the Spanish reforms.