Geographer's Space

Grandeur on Government Street

Baroque urban planning shaped Baton Rouge

Published: December 18, 2019

Last Updated: December 18, 2019

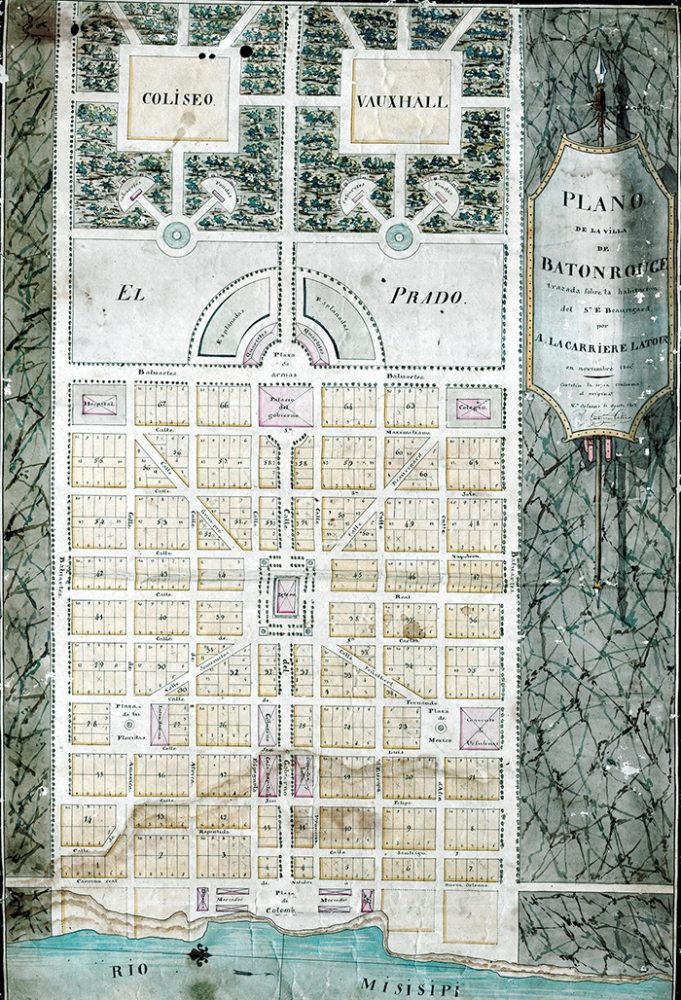

Beauregard Town plan, originally sketched in 1806.

Beauregard Town plan, originally sketched in 1806.

“Grand Manner” refers to the highly idealized genre of paintings and portraiture that positioned subjects in majestic settings of ancient statuary and allegorical figures. Popular during the long eighteenth century, the Grand Manner aimed to elevate mortal humans to stately and noble levels. It reflected the philosophies of the Enlightenment, which heralded dignity and valorized classical antiquity, and had corollaries in other fields. In rhetoric it was called the grand style; in music, baroque; in architecture it took the form of neoclassicism.

The signature element of this urban-design thinking, also known as Baroque planning, was a simple yet powerful feature—the diagonal boulevard. Consider the aesthetic power of diagonal lines: they have a certain theater to them, an audacity and flair not found in staid and predictable right angles. Restaurateurs know this when they slice sandwiches or fold napkins diagonally, as do fashionistas with their sashes and jaunty caps. Yet diagonals also uphold order and regularity; indeed, they need adjacent orthogonality to acquire the very bearings that make them diagonal. Thus their appeal in urban design: they bring both drama and rationality to the cityscape. They radiate like light (hence the synonym “radial” streets), yet they are also practical, allowing traffic to flow from core to periphery along convenient hypotenuses.

Diagonals, when they intersect, focus stage-like attention on spaces that may host parks or important buildings. Areas between and among diagonals are best subdivided as straightforward gridirons. The result is a panoply of geometric opportunities to showcase grandeur as well as accommodate the quotidian.

These ideas were put to cities both before and after the Grand Manner period in art. They appeared in Rome starting in the 1500s, and throughout Paris after its mid-1800s reconstruction under the oversight of Baron Haussmann. The concept became particularly popular for French cities and palaces of the 1600s and 1700s, after which two Frenchmen introduced the idea to the United States.

One was Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a Parisian art student turned American patriot and military engineer, who in 1791 was selected by President George Washington to design the new federal capital. L’Enfant’s plan exuded the Grand Manner spirit, its elements’ sizes and orientations thoughtfully arranged to spatially dramatize American ideals. For example, he positioned the legislative branch (US Capitol) more prominently than the executive branch (the White House) and ensured that all the apparatus of government would front a great open green for the people (the Mall).

As for the city’s street network, L’Enfant created a framework of diagonal axes intersecting at circles such as Dupont and Logan, and squares such as Farragut, McPherson, and Lafayette. He then infilled the interstices with a more or less orthogonal grid. The result was as spectacular as it was complex—perhaps a bit too complex. (More on that later.)

The other Frenchman to introduce the Grand Manner Plan to the present-day United States was Arsène Lacarrière Latour. He did so in a tiny outpost named Baton Rouge, which had been cleared of British control by the same Revolutionary War that enabled a new American capital on the Potomac. After the Revolution, Baton Rouge and West Florida transferred to Spanish dominion. Because its governors found themselves with a surplus of land and a deficit of hands, Spanish administrators were generous in distributing acreage to grantees who could afford upkeep.

One grantee was Elias Toutant Beauregard, a retired captain in service of Spain who came into possession of fine elevated land abutting the Mississippi. With the Louisiana Purchase signed in 1803 and adjacent territories now American, Beauregard and his neighbors sensed an impending boom, as Baton Rouge would now be Spain’s premier port on the Mississippi. Now was the time for speculative development, and Beauregard wanted something big.

In 1805 Beauregard hired a surveyor to sketch a plat for the river end of his plantation. Disappointed with the results, he hired another surveyor, who failed to deliver promptly. Beauregard then turned to a fellow Francophone recently arrived in New Orleans, and that was Arsène Lacarrière Latour.

Latour is renowned today for his later exploits in the Battle of New Orleans, as well as his engineering and architecture; perhaps his most famous legacy in New Orleans is the Girod (Napoleon) House, which he codesigned. But at this time, Latour was new to Louisiana, and this commission was one of his first projects. He inspected the modest confines of Beauregard’s provincial plantation and endeavored to turn it into something grand.

At the heart of Latour’s design were four diagonal avenues uniting at a centralized iglesia (church). Those four radials would terminate in two plazas closer to the river, named Floridas and Mexico, and two squares farther back reserved for a hospital and a college. Between them, and along the same axis of the iglesia, would be the Palacio del Gobierno (Governmental Palace) backed by a plaza de armas, a square where military forces could be displayed. That axis would become Government Street, and along its tree-lined flanks would be various official buildings.

Latour knew commerce would flow along the river and its parallel Camino Real (Royal Highway), so he put mercados (markets) there. He also recognized that, unlike in deltaic New Orleans where elevations dropped away from the river, here they rose, making the rear section of his plan ideal for Baton Rouge’s version of the Washington Mall. It comprised a landscaped prado (meadow, or lawn) complete with a coliseo and vauxhall (amphitheater and public garden), even fondas and cabaretes for snacks and entertainment. Off to the side was a convent, indicative of the Catholicism that was intertwined with Spanish colonialism. The entire plan was dazzling, and the most salient components, in both the urban and recreational sections, were the diagonal lines.

The entire plan was dazzling, and the most salient components, in both the urban and recreational sections, were the diagonal lines.

Streets were named for the usual saints, kings, and project patron, in this case Beauregard, but Latour went further, evidencing his worldly outlook. He called two prominent streets Espanola and Francesa, for the two nations from which both he and his client heralded, and named four parallels ones America, Europa, Africa, and Asia—a Grand Manner indeed.

Anyone who’s been to downtown Baton Rouge knows how this story ends. The grassy parks and markets are not to be found, nor are the centralized church or the governing palace, and only an ardent advocate would describe downtown Baton Rouge as being grand, much less baroque. Suffice to say that history got in the way of Latour’s vision.

But look closer and many of Latour’s key elements come into view: the four radiating diagonals, the interleaving grid, the central axis still named Government, and many of the original street names. The neighborhood is called Beauregard Town today, and according to historian Guy Clermont of the Université de Limoges, it represents “one of the rare existing examples in the United States of what is often referred to as the genius of French urban planning.”

A 2018 Google Satellite image of the same area in downtown Baton Rouge today. Note the clear diagonal layout below the interstate. Google Satellite

To be sure, others may be found in New Orleans, in the French Quarter as well as in the Coliseum Square area, which was designed in the same year (1806) and by a kindred spirit (Barthélémy Lafon) as Latour’s Baton Rouge project. But the French Quarter was by no means baroque, and Coliseum Square was only partially so. This leaves Beauregard Town a real rarity.

Full-blown Grand Manner plans fell out of favor as cities grew more crowded and transportation mechanized. The designs weren’t particularly friendly to pedestrians either. Anyone who has negotiated Washington, DC, can attest to the difficulty of perambulating a particular street as it intersects a rotary fed by many other streets, some very wide, all swirling with traffic. Dupont Circle, for example, is a hub to ten spokes, and numerous oblique angles splaying through the cityscape have a way of disorienting all but the most seasoned locals. Grand Manner plans, in short, work better on paper than in pavement.

Diagonals, nevertheless, still inspire urbanists for their majesty and convenience. Evidence of their enduring appeal comes from many modern planned cities, among them Brasília and Belo Horizonte in Brazil; Canberra and Adelaide in Australia; and La Plata in Argentina. They are urban theater, creating the spaces and places that make cities interesting.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, Bourbon Street: A History, and other books. He may be reached at [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.