Winter 2025

Louisiana’s Hilliest Municipality

A topographic visit to Harrisonburg

Published: December 1, 2025

Last Updated: December 1, 2025

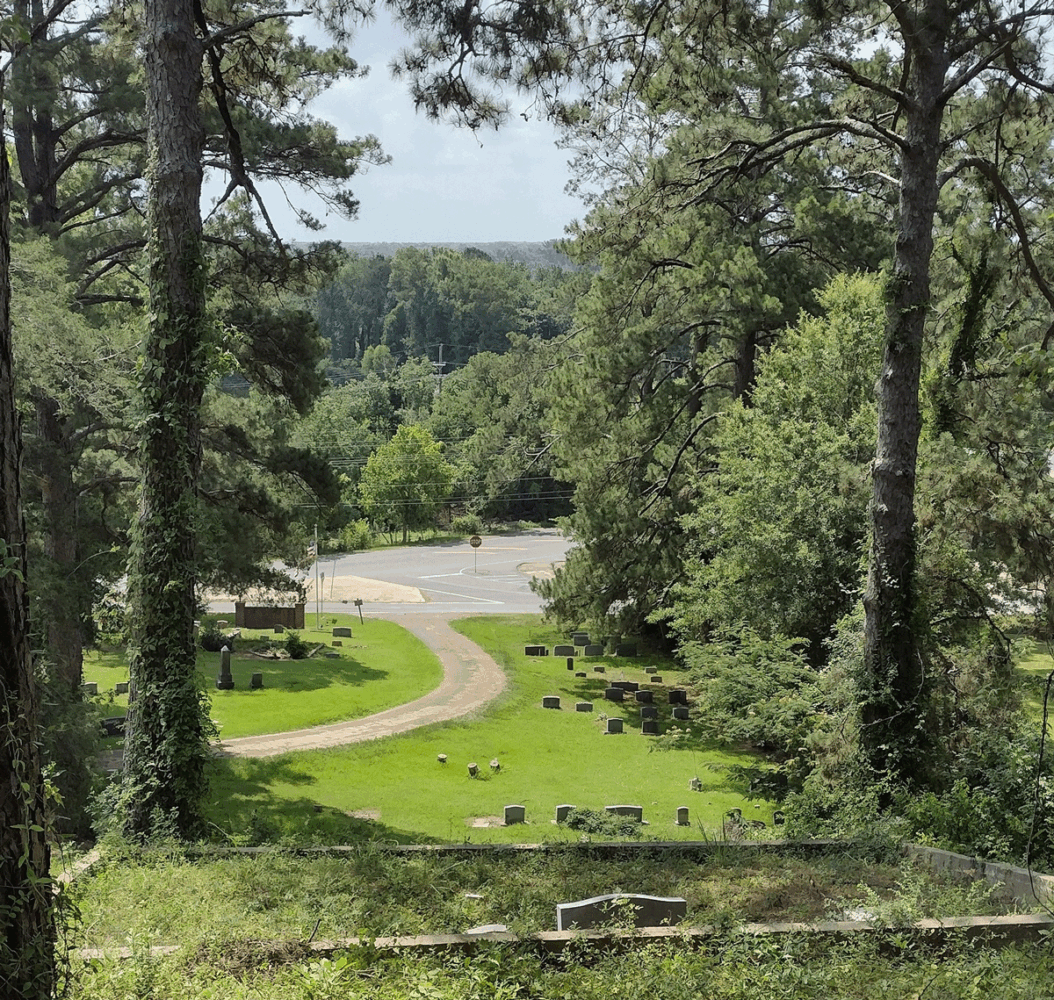

Photo by Richard Campanella

Fort Hill Park, over 190 feet high, looking down on Harrisonburg at fifty feet.

I’m usually cautious about superlatives. “The first,” “the largest,” “the tallest,” “the last”: such characterizations are catnip for contrarians, and for good reason, as they often rest on subjective definitions or conditional statements. Better to couch your claims with weasel words like “among the largest” or “one of the last.” As I tell my students, I’d rather be a right weasel than a wrong superlative.

But I’m going to go out on a limb—or rather a bluff—in claiming that the Village of Harrisonburg in Catahoula Parish is the hilliest municipality in Louisiana. I might even say the ruggedest.

Admittedly, that’s not saying much. By my calculations, Louisiana is the third-lowest state in the nation, with a mean elevation of 98 feet above sea level, after Florida (63 feet) and Delaware (44 feet). We’re also the third flattest, with one foot of vertical change for every 373 horizontal feet of land.

To me, all that flatness makes topography that much more interesting to study in Louisiana, because the less you have of a critical resource, the more valuable it becomes. Think of an oasis in a desert, or a port in an otherwise landlocked country. Think of the importance of a slight ridge in coastal Louisiana, or of the natural levee in deltaic New Orleans.

I’m going to go out on a limb—or rather a bluff—in claiming that the Village of Harrisonburg in Catahoula Parish is the hilliest municipality in Louisiana.

Harrisonburg, an incorporated village with some 270 residents, sits on the west bank of the Ouachita River, roughly halfway between Alexandria and Vicksburg, Mississippi. While most of its dozen or so streets occupy a level riverside perch and its municipal limits extend out to an equally flat eastern bank, Harrisonburg’s western flank rises dramatically behind Bushley Street, the main drag into town. So far as I have been able to determine, this topography gives Harrisonburg the steepest slope—that is, the highest vertical rise within the shortest horizontal distance—of any municipality in the state.

Elevations in the village start at 50 feet above sea level along the banks of the Ouachita and rise up to over 190 feet at Fort Hill Park, some 900 feet away. Most of that inclination occurs within half that horizontal distance, yielding slopes of 15 to 20 degrees in a state whose average slope is 0.152 degrees, and whose steepest parish (Lincoln) averages 0.46 degrees. That makes Harrisonburg 30 to 40 times steeper than hilly Lincoln Parish, and over a hundred times steeper than the Louisiana average, all within municipal (village) limits.

This landscape formed when, at the end of the Ice Age, winds mobilized deposits of silt left behind by the retreating glaciers and dropped them a few hundred miles downwind. Those silt particles that landed upon the older, uplifted areas of northern Louisiana and western Mississippi formed undulations of finely textured reddish soil called loess, from the German löss or los, meaning loose. Loess can erode into hillocks with steep ravines, sometimes even cliff faces and hoodoo-like escarpments quite unusual for this region. Those silt particles that landed upon the valley of the lower Mississippi and its tributaries, including the Ouachita, mostly got swept away by flood cycles, leaving behind some island-like formations such as Crowley’s Ridge, the Bastrop Hills, Macon Ridge, and Sicily Island.

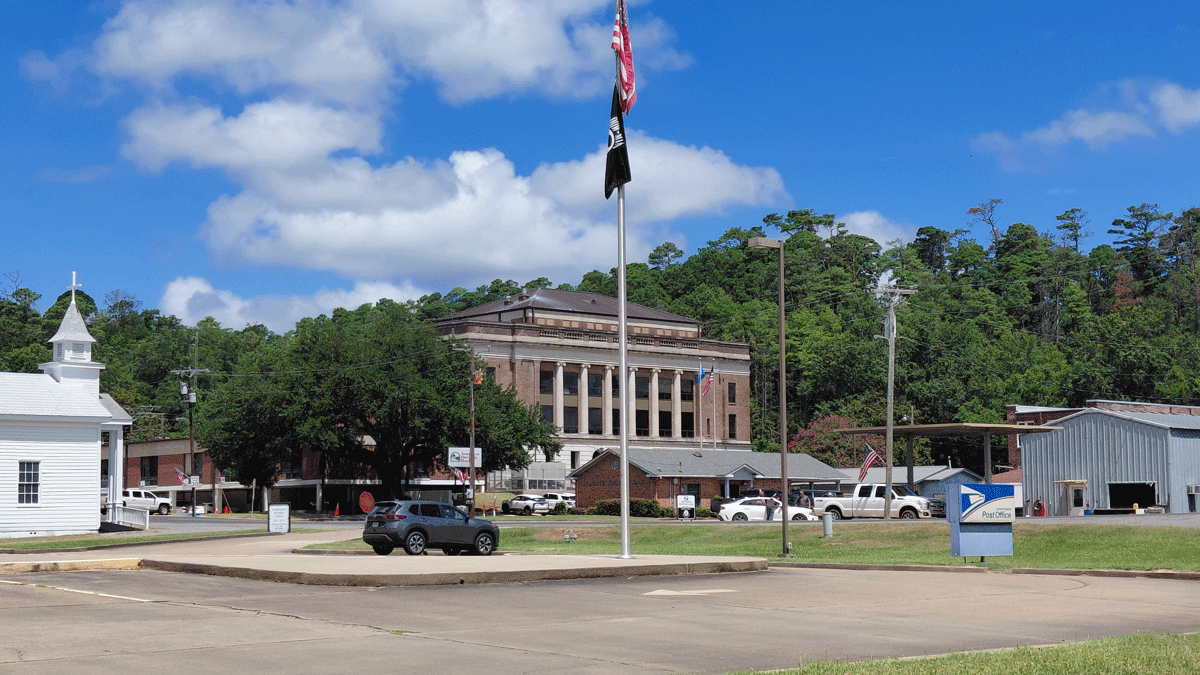

The Catahoula Parish Courthouse. Photo by Richard Campanella

The most rugged loess bluffs formed where the largest waterways scoured directly into thickly accumulated layers of loess. In the case of the Mississippi River, this scouring explains why Yazoo City, Vicksburg, Natchez, and St. Francisville all have steep river-facing bluffs. In the case of the Ouachita River, the scouring yielded the steep slope behind Harrisonburg as well as that of Columbia in Caldwell Parish, whose comparably interesting topography includes a section called Columbia Heights up from the historic river district. It just so happens that Harrisonburg’s loess bluffs start lower and rise higher.

Natives had been active in the Harrisonburg area as early as two thousand years ago, as evidenced by two mounds located just off Taliaferro Street, and their hunting trails may explain why a river crossing initially formed here. Stories that a French fur-trading post operated in Harrisonburg in 1712–1714 inspired local boosters to include “Founded 1714” on the village entrance sign (above “Home of the Bulldogs”). Other sources trace Harrisonburg’s origins to a Spanish land grant made to John Hamberlain in the late 1700s, followed by designation in 1808 as the seat of the newly created Catahoula Parish, after which a store and ferry opened in 1809. Hamberlain subsequently sold the land to John Harrison, who in 1818 hired Edward Dorsey to lay out street and blocks under the name Harrisonburgh (the second “h” was later dropped).

Terrestrial traffic came into town along the famed Harrisonburg Road, which connected Natchez and points east with Natchitoches and points west. This wilderness pathway was first blazed around 1800, made into an official public road in 1825, and served by stagecoaches starting in 1849. The Harrisonburg Road helped spawn at least six lasting settlements in Louisiana (Vidalia, Harrisonburg, Jena, Georgetown, Atlanta, and St. Maurice) and earned Harrisonburg its first post office in 1822, just as steamboat traffic began calling regularly at its river landing. The town benefited additionally by being the head-of-navigation point on the Ouachita during autumn low-water periods, conveniently coinciding with the cotton harvest.

In travel notes published as “A Tourist’s Description of Louisiana in 1860,” J. W. Dorr observed, “Harrisonburg is a handsomely built and thriving town of some three or four hundred inhabitants, and is beautifully situated on a high bluff, but at the foot of a still loftier hill . . . coated with . . . a lusty growth of forest trees[—]a very prosperous commercial point.” When the Civil War erupted the next year, Confederate generals fortified that “still loftier hill” to guard the Ouachita from federal gunboats. Later named Fort Beauregard, the position saw action in three separate engagements during 1863–1864.

Harrisonburg incorporated as a village in 1872, and saw its population gradually rise from 243 in 1880 to about 500 in the mid-1900s. According to an unpublished manuscript written by Elmer I. Gibson in 1972, the Village of Harrisonburg in 1930 acquired thirty acres atop Fort Hill, “considered to be one of the most beautiful spots in Catahoula Parish, with a stand of virgin pine timber, and . . . a commanding view of the beautiful Ouachita River . . . It has been used for family gatherings, religious crusades, [and for] playgrounds for the young and old.” Gibson might have added a superlative: it’s the highest point in Louisiana’s hilliest village. Now known as Fort Hill Park (Fort Beauregard Veteran’s Memorial Park), it affords glimpses of the horizon through gaps in the towering pines.

Like so many rural Louisiana communities, Harrisonburg’s historical advantages did not age well in modern times. The village’s catchment area never had many people or much economic production, and when cotton shifted westward, most of that produce went with it. Stagecoaches and steamboats lost passengers to trains and autos, and because Harrisonburg landed neither a railroad nor a four-lane highway, few people now have a need to pass through. Harrisonburg’s population of 750 residents in 2000 has since plunged by two-thirds. The courthouse and affiliated parish operations now account for most of the village economy, though a recent effort to improve the riverfront has potential—as does, I might add, anything that might capitalize on Harrisonburg’s unique urban topography.

In a state as flat as ours, it’s fascinating to see how Louisianans respond to rare ruggedness. Stroll around town and you’ll see concrete staircases rising up to porches, some with twelve to twenty steps. Many yards are steep enough to roll a mower. The cemetery (there are actually two, immediately abutting, a relic of segregation) is surely the most undulating in the state. It has a number of terraces built into the hillside to flatten the land for burials, quite the opposite of the “cities of the dead” for which Louisiana is famous. At the 175-feet crest of the Harrisonburg Cemetery, vistas of the Ouachita Valley may be enjoyed from vantage points even better than at Fort Hill Park. And on the wall of the farmers’ market pavilion at the entrance of town, a folksy mural captures the Harrisonburg of two hundred years ago—complete with a reasonable depiction of its superlative hilliness.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and Built Environment, is the author of Crossroads, Cutoffs, and Confluences: Origins of Louisiana Cities, Towns, and Villages; Draining New Orleans; Bienville’s Dilemma; and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on X.