Summer 2025

The River Meanders

Looking at the oxbow towns of Louisiana

Published: May 30, 2025

Last Updated: May 30, 2025

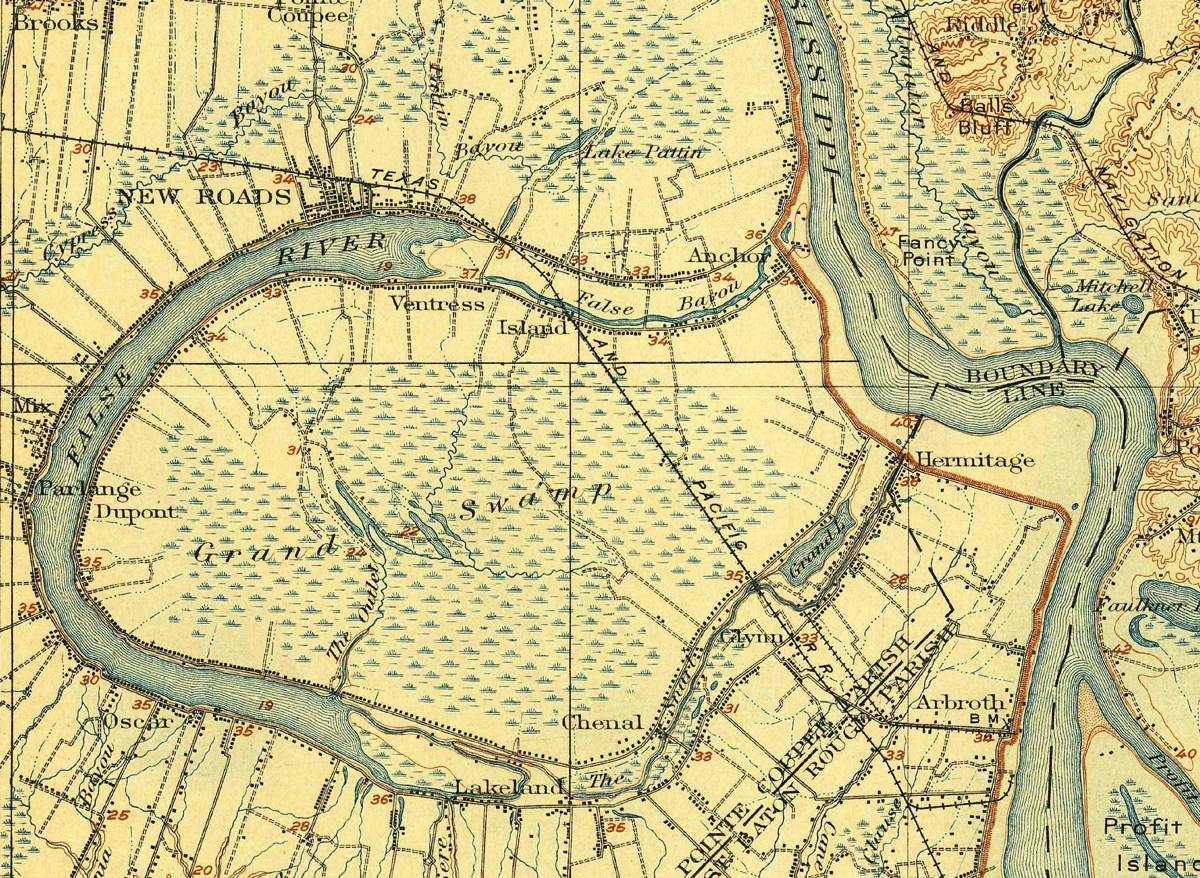

A 1906 map showing the town of New Roads on False River.

US Geological Survey

To a degree probably unmatched across the continent, Louisianans inhabit natural levees, those slightly elevated landforms abutting meandering rivers, shored up by alluvium deposited over centuries. Roughly one-third of our state’s population reside on or near these fluvial features, including the entire deltaic plain of the lowermost 220 miles of the Mississippi, as well as the bayous of Lafourche, Terrebonne, Teche and all their interconnecting ridges. Other inhabited natural levees may be found along the meander belts of the Red and Ouachita Rivers, and along the current and former channels of the Mississippi River from East Carroll Parish down to West Baton Rouge Parish.

Natural levees are beholden to all the complex dynamics of sediment-laden rivers, and under the right conditions, those dynamics can spin off a geomorphological curiosity known as cutoff meanders. They occur when a river bends so circularly that the narrowing neck of remaining soil weakens through filtration and finally gives way. Once the river detects the new steeper gradient, it lunges in with increasing speed and power and eventually “cuts off” the old meander, turning it into a curvaceous lake.

If unfed by a new source of water, these landlocked waterbodies eventually clog up into morasses bordered by relict natural levees, whose swirling patterns may be seen abundantly in geological maps and satellite images. Those cutoff meanders that manage to impound water are called oxbow or horseshoe lakes, of which Louisiana and adjacent parts of Mississippi and Arkansas have many fine examples.

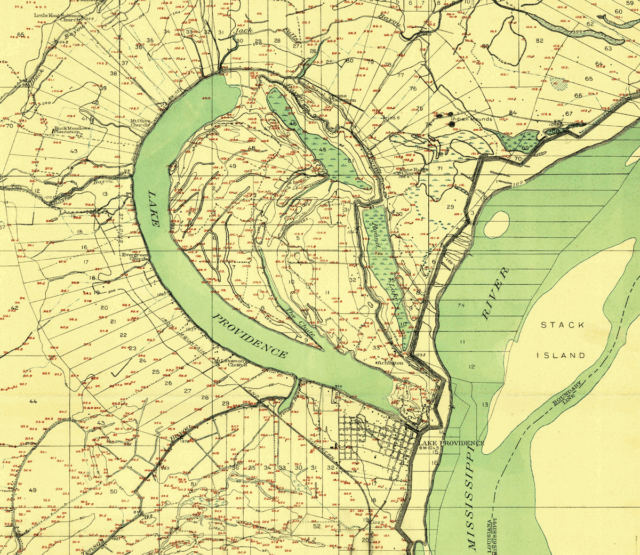

A 1909 map showing Lake Providence. US Geological Survey

A 1906 map showing the town of New Roads on False River. US Geological Survey

Oxbow lakes made for attractive settlement sites, relatively speaking. Because terrain originated as natural levees, they rose above the surrounding bottomlands, while soil textures were coarser and therefore loamy and fertile. They remained close to the active river channel but were no longer threatened by its flood cycles or erosive flow. Yet they still benefitted in regard to potable water, irrigation, fisheries, and local navigability within a stable harbor-like lake.

Depending how you count them, Louisiana has a dozen or so oxbow-lake communities, and together they are home to about twenty thousand people. Among them are New Roads on False River; Batchelor on Raccourci Old River; Ferriday on Lake Concordia; Spokane on Lake Saint John; Lake Bruin; Newellton on Lake St. Joseph; and Lake Providence.

Not all are textbook cases. Ferriday arose primarily on account of a circa-1903 train station, which just happened to be on the natural levee of the oxbow Lake Concordia—whose formation got a hand from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1933. Others are tiny hamlets that arose at crossroads; Newellton, for example, formed on the natural levee of the oxbow Lake St. Joseph to provide ginning services to adjacent plantations, which it still does. We find textbook cases of oxbow-fronting natural-levee settlements at the extremities of Louisiana’s upper-delta region, namely New Roads in Pointe Coupée Parish and Lake Providence in East Carroll Parish.

Thus was born New Roads, Louisiana [. . .] the handiwork of one of the very few women or persons of color to have established a modern-day Louisiana city.

New Roads overlooks the perfect oxbow lake known as False River, described by geomorphologist Hilgard O’Reilly Sternberg in his 1956 dissertation as “the lower-most cutoff[,] the oldest to be completed within historic times, and one of the longest meander loops ever formed by the Mississippi.” The meander began breaking off from the Mississippi in time for Robert La Salle to note it during his 1682 expedition to claim Louisiana. In 1699, Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, and his crew, having been advised by Natives of this convenient shortcut, cleared debris along the 350-foot-long neck to get their longboats upriver. Once the current broke through the pointe coupée (“cut point”), it widened and sent more water into the main channel, while dropping more sediment through the now-slack cut. Within a few years, the loop broke off from the channel to become a ten-mile-long lake dubbed fausse rivière—“false river.”

Enough colonists arrived at Pointe Coupée to warrant its inclusion in the Louisiana census of 1722. Four years later, French authorities established a fort and barracks here, and by the early 1730s, the area was home to 55 white settlers as well as 53 enslaved Africans and three enslaved Natives. By the end of French dominion, some 500 white residents and 700 enslaved people worked 117 plantations spanning the natural levees of the False River oxbow lake, while 38 soldiers manned Fort de la Pointe Coupée.

France’s transfer of Louisiana to Spain, followed by its defeat in the French and Indian War, put False River near the boundary between two mortal enemies. With the British just across the river, Spanish authorities made what they called Punta Cortada a priority to populate for both defensive and economic reasons. They did so by granting land to white settlers and importing hundreds of captive West Africans to cultivate indigo, tobacco, corn, and cotton.

Increasing traffic between the riverfront fort and the False River plantations required that a road be blazed between their two natural levees, which gained the name Chemin Neuf or Camino Nuevo (New Road), to distinguish it from the older Camino Real (Royal Road). The new artery brought action to the northern bank of False River, all the more so following the departure of the British, later the Spanish, and finally the arrival of the Americans. In 1804, American officials created Pointe Coupée Parish out of the preexisting ecclesiastic parish of the same name, and in 1806 designated the old fort to be the parish courthouse. That put more traffic on the New Road, specifically to the property of a free woman of color named Catherine Depau (also known also as La Fille Gougis, or Gougis’s Daughter).

A sign depicting the river cut that is Pointe Coupée’s namesake. Photo by Richard Campanella

According to Brian Costello, author of A History of Pointe Coupée Parish, Louisiana, Depau in 1822 “created a six-block, 20-lot subdivision of the front part of her False River plantation, bordered on the east by the New Road [and now] bounded by False River, Second Street, New Roads Street, and St. Mary Street.” Thus was born New Roads, Louisiana, on the natural levee of an oxbow lake, the handiwork of one of the very few women or persons of color to have established a modern-day Louisiana city. The historic district of today’s New Roads would be readily recognizable to folks of the mid-1800s, even as False River’s once-turbid waters have given way to pontoon boats and water skiers.

Around 218 wending river miles upstream is another municipality perched on the natural levee of an oxbow lake, and although it is roughly the same size as New Roads, it is far poorer and more isolated. The town of Lake Providence, set upon the oxbow of the same name, traces its origins to the turn of the nineteenth century, at which time growing numbers of Americans navigated the lower Mississippi en route to New Orleans. They called into need convenient river landings for rest, resupply, and trade, all of which required shelters, depots, and basic services. When Spanish officials denied their right to deposit cargo at New Orleans in 1795, the American boatmen began using a particular island in this vicinity to warehouse cargo, earning it the name Stack (or Stock) Island. To create access to the island from points west, frontiersmen blazed a trail connecting Fort Miró (future Monroe) with present-day Bastrop and Oak Grove and terminating at a suitable bankside site where the natural levee of a meander had broken off from the main channel. This oxbow lake still had incoming water, which discharged as a bayou that flowed south to become what is now the Tensas River—a rare case of a named river born of an oxbow lake, and one that created its own natural levees.

This particular oxbow abutted the Mississippi along a relatively straight channel segment, making it easier for docking. Only two miles away was Stack Island, with its valuable cargo in transshipment, and more than its share of ruffians. According to local sources interviewed by Works Progress Administration historians in the 1930s, so perilous was navigation around the roguish island that traders “were wont to say, “[if] we reach the lake below Stack Island, it is Providence.” More likely, the heavenly name aimed to attract residents and traders; either way, the name stuck, and eventually both the oxbow lake and its community became known as Lake Providence.

During the opening years of American dominion, Anglo-Saxon settlers with names like Floyd, Culfield, Collins, Bruit, White, Hood, Barker, Demsey, and Millikin began claiming tracts by Lake Providence. Bottomlands were cleared for cotton cultivation, and with the rise of steamboats in the 1820s, Lake Providence became a portal for northern Louisiana to reach national and global markets. Likewise, the growing town became the gateway for stagecoach roads to access Monroe, Shreveport, Greenwood, and the Texas frontier. Designated the seat of the new East Carroll Parish when it was separated from West Carroll in 1877, Lake Providence surpassed 1,500 in population in the early 1900s, by which time it had “two banks, a number of good stores, hotels, lodges of various secret and benevolent orders [and] a good municipal government,” according to historian Alcée Fortier writing in 1914. It also had three river landings, ferry service, mills for lumber and cotton seed oil, and a station on the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern Railroad, making “it a good shipping and distributing point [for] a profitable wholesale business, especially in groceries.”

But over the course of the twentieth century, most of historical siting advantages had disappeared. Cargo shifted to rails; cotton moved westward; and the timber had all been cut. Lake Providence’s population peaked in 1980 with 6,300 people, and has since fallen below 3200 residents. Described as “the poorest place in America” in a 1994 Time Magazine article, Lake Providence suffered additionally for having no major highway, no bridge, no more ferries, and hardly any through traffic. Yet the community endures, for its administrative role as a parish seat; for its service and trade economy; for its spirited and determined population; and for its fine perch on the natural levee of a textbook oxbow lake.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Draining New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and Crossroads, Cutoffs, and Confluences: Origins of Louisiana Cities, Towns, and Villages (LSU Press, 2025). He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on X.