Rooted in Louisiana

A conversation with Shreveport-native and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown.

Published: February 28, 2022

Last Updated: November 26, 2023

Photo by John Lucas

Jericho Brown.

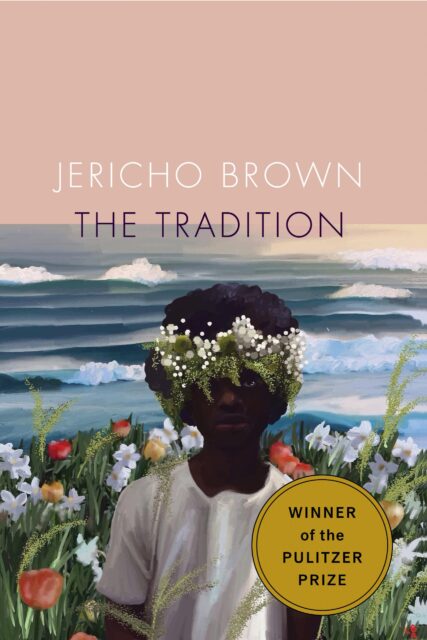

In the summer of 2020, contributor Kelly Harris-DeBerry spoke with Shreveport native Jericho Brown about growing up in Shreveport and how New Orleans shaped his outlook as both a person and poet. Brown reflects on the influence of civil rights leader Reverend Harry Blake (who faced police brutality in response to protest efforts following the 1963 Birmingham church bombing), the role of Louisiana’s natural landscape in his poetry, and his time spent in New Orleans—as a student at Dillard University, a speech writer for Mayor Marc Morial, and a young poet wrestling with words in the NOMMO Literary Society’s workshops. Winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his third poetry collection, The Tradition, Brown is the Charles Howard Candler Professor of Creative Writing at Emory University in Atlanta, where he directs the creative writing program.

KHD: The Tradition won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. Congratulations. You’ve described this book as being pastoral. I like how you use nature as a lens to explore our human nature. It had me thinking about Louisiana’s lush and beautiful landscapes, but also how it contradicts its own beauty.

JB: Yes! What I love about having moved back to the South is that some of it is the same. There’s a poem in the book called “The Trees.” There are four crepe myrtles in my front yard, now, where I live. I can see them when I look out the big window in my living room. Often, I sit and I work there. I’m sort of gazing out of the window, meditating or ruminating. That triggers me to my first experiences with crepe myrtles, which really were with my mom and dad, working outside in the yards, all over Shreveport and Bossier, where my dad worked. He literally worked with his hands for a living, which means that’s what I did too, that’s what we all did.

And I think that experience is the reason why I have such a relationship to the land in my poems. Not to mention the fact that it’s not just my mom and dad, it’s everybody in my family. My grandparents on both sides of my family were sharecroppers. They were literal farmers, they picked cotton. My grandad and all of his thirteen kids, they picked cotton. Do you know what I’m saying?

KHD: Yes. Sounds like my grandparents’ southern story.

JB: And Kelly, you know this, not being born in the South. When you drive by a field of cotton you be like, oh, my God, that’s what y’all had to do? That’s what y’all was doing from sunup to sundown? Obviously, my relationship to the land is intertwined with my conception and idea of work, which is intertwined with my conception and idea of race. Often, you see a tree, or a flower, or even an animal, a bird, a rabbit, when you see that in The Tradition, what you’re seeing, in my mind’s eye, is an image that is indeed in Louisiana.

KHD: Has the Pulitzer changed your life in ways that you didn’t expect?

JB: I won the Pulitzer in early May 2020. It was difficult to win and be in isolation during the pandemic. I was a little sad because, of course, you want to promenade. This is my crown and this is my scepter.

It was really a mixed, bittersweet emotion. I do feel that from March [2020] until now, poets have been called upon in ways that we have not seen in our lifetime. We’ve been needed. I think, for all of us as poets, we have a better feeling of our worth—I hope we do, in this moment, maybe more than we did before. People need art, and you don’t realize how much you need it until there’s a sense that it might disappear from your life. If a tree is an example of God’s nature, then a poem is an example of man’s nature. You don’t know what part of your body a poem is healing. But, if there were not poems there, you would be in way more pain.

KHD: Absolutely. Speaking of health and healing, it’s known that you are living with HIV. I’m interested to know what it’s been like to live with the threat to your health while simultaneously being consumed with worries about COVID and the wellness of your friends and family.

JB: There is that, but I really had a lot of health issues in 2019 and 2020. I kept seeing doctors who couldn’t tell me anything. It was really difficult for me because I was in a lot of pain. Something about that was readying me for all the illness and death that I would see.

It’s been a hard time for so many people, and a really hard economic time for a lot of people. It reminds me where my nation’s values really are. The rush to find the cure or a vaccine, I should say, for the coronavirus, really just has to do with economics. If that weren’t the case, people would just be dying. I think the hardest thing about the coronavirus was that you didn’t have, and in many instances still don’t, the opportunity to be there for one another. There are still people who haven’t seen their parents in a year and a half or more.

I hope people became aware of how much we need each other. I hope we hold onto the value of touch and proximity and being there with somebody. I do think, as it relates to HIV, that in the gay community, there’s a lot more acceptance among us about, not just HIV but various conditions that queer people are living with. I hope that there is more acceptance of us, in terms of different ways of being queer. In the same way that I hope there is more appreciation for proximity since the coronavirus, which isn’t over.

Kelly Harris-DeBerry: You were born and raised in Shreveport, Louisiana. Describe Shreveport to someone who has never been there.

Jericho Brown: The city is very divided, as it relates to race. It’s a conservative city, really, even among Black people. Black people can be conservative, even if they’re voting for Democrats, because of that religious aspect.

KHD: Your church was Mt. Canaan Missionary Baptist Church, right?

JB: Yes. Reverend Harry Blake was the pastor. He recently died of COVID, which was very sad and difficult for me, because when you experience a COVID death in your life, you can’t grieve in a communal way. Pastor Blake was a civil rights leader and a part of the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference]. Things were very Black, in that spiritual way. But things were also very Black in that political way. On one occasion, police marched into the church and started beating the parishioners and the people who were at the rally. Pastor Blake was beaten within an inch of his life, so horribly that he almost died. Part of the reason why he almost died is because after he was beaten so badly, they couldn’t take him to a hospital in Shreveport. I think the legacy of that was always around that church. You know there are these parts of your life, Kelly, that you weren’t there to see and yet they’re at your backbone. It’s as if they’re part of your own experience.

But, there was . . . I should say, because you asked, there was poetry in the church. My church was really deep in educations of the Bible in a way that, at the time I took it for granted. It was always made clear to us what passages from the Bible were letters, and what passages from the Bible were prayers, and what passages from the Bible were poetry. And there’s always a program, or a pageant, or a play.

But, the other thing, and I don’t know if it was like this for you, Kelly, but I know in my church growing up and I think in many other churches, young people recited “Phenomenal Woman” or “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou, or “Ego Tripping” by Nikki Giovanni, [or] “Mother To Son” by Langston Hughes. I was getting poems in church and I was also getting them in school.

KHD: You left Shreveport for Dillard University in New Orleans. Was that an easy choice for you?

JB: My cousin attended Dillard and did well there. Dillard used to do this recruitment program at Freeman & Harris Cafe, a Black-owned restaurant [in Shreveport] famous for the people who came and ate there and the role they played during the Civil Rights Movement. My cousin and other students talked about Dillard. I remember thinking, wow, these kids are so smart. They were quoting Malcolm X in the middle of speaking. Also, there was a lot of folks from Shreveport who had gone to Dillard; there was a large contingency of us. When you went to Dillard, people who found out you were from Shreveport [would] treat you well.

KHD: Was it important for you to go an HBCU [historically Black college or university]?

JB: There was no other option. Growing up, my mom and dad would say things like, “If you don’t get a scholarship, you ain’t going to be able to go to school, you going to have to go to the Army.” Or they would say, “You have to go to a Black school. We not paying for you to go to no white school.” And I would think to myself, wow! How are these the same?

I just wanted to go to Dillard because it was in New Orleans and I understood what New Orleans was, in comparison to Shreveport. When you grow up in Louisiana, New Orleans is the city.

I understood, even then, that I was queer. I didn’t think that was anything I could even tell myself. Yet I understood it. I also had this idea that college would be a lot easier for me in New Orleans than it would in Baton Rouge. New Orleans is a great place. Maybe it’s not great for everybody, so I shouldn’t say that, but it was a great place for me to realize my sexuality.

KHD: After Dillard, you worked for Mayor Marc Morial. How did that job prepare you to be a poet?

JB: I was a speechwriter for then mayor Marc Morial and that’s when I really got to know New Orleans. You could live in a bunch of cities in this world but you don’t feel no responsibility to love them. When you’re in New Orleans you feel like, I have a responsibility to this place. I have a responsibility to its kids, its older people. You feel a sense of community, immediately. I should say I feel it less so in Atlanta. Atlanta seems to run without me. When you’re in New Orleans, you feel like it needs you.

KHD: At this time you were working for the mayor and you were also participating in the NOMMO Literary Society’s workshops. I’m curious to know how that workshop, led by Kalamu ya Salaam, shaped you as a writer?

JB: I think the big, and most important, thing I learned in NOMMO is how to be good and hard on myself. You have to be both in writing. You sit down with all of your history, and everything you know, and everything you can imagine, everything that you can create that’s not really there, everything you see when you’re high. You know what I’m saying? All of the surreal aspects of your imagination. You sit down with that, and you sit down with everything you know about poetry.

You’re sitting down with all those things, and you have to allow yourself to be overcome by them. So, it’s a good idea to be nice to yourself and to allow yourself to fumble, to mess up. I think I learned that from NOMMO, how to be more capacious as a reader and a writer, and how to allow for everything to come in, and then out in the poems.

KHD: One of the things I heard about NOMMO is that workshopping could be brutal.

JB: NOMMO was cutthroat, they would wear your ass out. I don’t think that would be good for everybody, but it was great for me. I needed to be cool with Jericho. And then, when it’s time to go back and look at things, I need to be vicious with Jericho.

KHD: I’m curious to hear about your experience at University of New Orleans. There are obvious differences between Dillard and UNO, but where were you in your development as a writer at this time?

JB: I actually started an MBA program at UNO, but I could not pay attention and I could not show up. So, I stopped doing that and I started taking writing workshops. I liked writing poems. I liked reading. In my head, I was just thinking, if I have an MFA [in creative writing], everything will be fine because I can just go get a job at Dillard.

I had really good teachers who were wonderful to me. UNO was different, culturally, because I had to deal with microaggressions and didn’t have that word, at the time. Microaggressions are easier to deal with when you have the word. I hadn’t had to deal with that at Dillard. But, I was also . . . How do I say it? I was also fine with that. I wasn’t invested in a way that it could completely harm me.

KHD: What advice would you give to MFA programs generally or as it relates to Black students coming into their programs?

JB: As a person who runs an undergraduate program, the first thing is: faculty needs to be reading. Everybody’s caught up on a diverse faculty and I agree, it’s useful. But it’s more useful to have faculty who are willing to be diverse readers. When I was pursuing my PhD, I would go to my professors’ houses for events and I would go to my classmates’ houses and look at their bookshelves—they just wouldn’t have any Black people on their bookshelves.

It became a sort of a game and goal. I wanted to see, who you got on your bookshelf that’s Black? And not even just Black—there would be nobody of Asian descent, no Latinx people. I’m like, no wonder y’all are treating me shitty.

Be a diverse reader. The more you read you’ll know about the strategies of various kinds of poetry, or fiction, or nonfiction, or playwriting, or screenwriting, or whatever you’re teaching in your program—[and] the easier it’ll be for you to teach strategy that is also diverse. People are out here trying to teach meaning, trying to teach morals, trying to teach all these other things that I don’t think you can teach, to be quite honest, not in a creative writing workshop.

I do feel that from March [2020] until now, poets have been called upon in ways that we have not seen in our lifetime. We’ve been needed. I think, for all of us as poets, we have a better feeling of our worth—I hope we do, in this moment, maybe more than we did before.

KHD: Thank you for being so gracious and vulnerable. Do you think you’ll ever return home to Louisiana?

JB: I think I could live in Shreveport for a semester. If I was teaching at Centenary or something like that, I think I could do that for a semester. New Orleans? I think I could live there again, except I’m always so sad when I go there, then I think I can’t. When I’m home in Atlanta, or when I’m traveling, I still think of New Orleans as home, Kelly. But the home that I had hasn’t been there since Katrina. When I go back there, I don’t get the sense that it’s the same place that I left.

I could probably live a year in New Orleans, to see what was up. Like, should I stay in New Orleans? That’s the question. People do ask me a lot, Kelly, even when I’m not doing something that is Louisiana-based: would I move back to Louisiana? I think I could live in New Orleans again.

Kelly Harris-DeBerry is a poet and the author of Freedom Knows My Name. Read and listen to more of her work at kellyhd.com