Winter 2015

The Great Outdoors

Greek theaters and their modern offspring have been springing up across Louisiana

Published: December 1, 2015

Last Updated: January 3, 2019

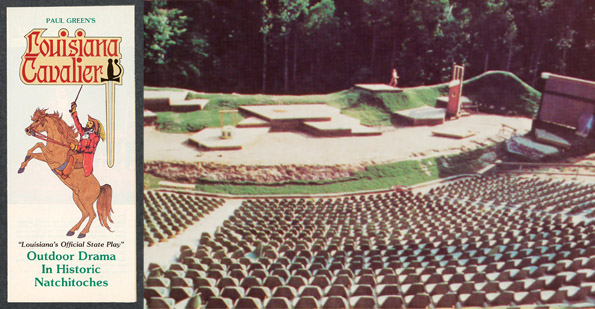

One short-lived Greek-inspired theater was built in Grand Ecore in the 1970s. It was the product of the newly formed Louisiana Outdoor Drama Association (LODA) in Natchitoches, which inaugurated a series of open-air historical dramas that were held for ten weeks every summer. Drawing on the classical sources of dances and songs, the association commissioned Paul Green’s Louisiana Cavalier for the opening show. This was an imaginative and swashbuckling music-and-dance interpretation of French explorer Louis Antoine Juchereau St.-Denis’ encounter in the early 18th century with the area’s Native Americans and Spanish inhabitants. Designed by Natchitoches architect E. P. Dobson Jr., the amphitheater was built near the spot where this historic event supposedly took place. The structure took the general form of an ancient Greek theater, but the stage was slightly elevated, deviating from the circular floor (the orchestra) design of beaten earth found the original classical versions. But like many of them, the stage’s backdrop was simple, consisting essentially of a row of trees. LODA’s shows continued for only a few years at Grand Ecore and the building’s site is now occupied by the Natchitoches Shooting Range.

In Baton Rouge, a Greek theater was conceived as early as 1921 for Louisiana State University. When ultimately built, it occupied a depression formed by the side of a pond. In his book, The Architecture of LSU (2013), J. Michael Desmond tells the story, illustrated by original plans, of the evolution of the theater to its current configuration. Initially, the seating area was a grassy slope looking down over a low stage; the existing stepped concrete benches date from the 1930s. Formal gardens to the rear of the amphitheater’s stage area included a reflecting pool surrounded by semicircular paths bordered by plants and trees. However, in 1960, because of problems from stagnant water and mosquitos, the pool was filled in. The theater’s seating area, which is almost a full semicircle, can accommodate an audience of approximately 3,500, and radial staircases divide the concrete benches into wedge-shaped segments. The stage, which is raised, projects into the curve of the seating and a row of trees forms its backdrop. Although not as bucolic as in its initial conception, the amphitheater, partially shaded by trees, makes a secluded and peaceful escape on this busy campus when it is not in use for events.

In the 1970s an amphitheater was constructed in Grand Ecore, near Natchitoches, Louisiana. The drama Louisiana Cavalier was staged for a few years during the summer months. Courtesy of East Carolina University, 35528

Shreveport can count two open-air theaters. The earliest built, and the one that is closest to the Greek theater’s architectural origins, is the Hargrove Memorial Amphitheater at Centenary College. Set in the slope of a shallow depression, it was constructed in 1926, with banks of wooden seating and bordered by trees and gardens. In 1936 the facility was reconstructed with concrete bench-type seating and enlarged to seat 2,000 rather than the initial 1,700. A deep round-arched band shell was added to the stage in 1964, which not only improved acoustics, but protects musical and concert performers from inclement weather.

Shreveport’s second amphitheater is much more recent. It is one of the resources in Riverfront Park and overlooks the Red River. Although less true to a Greek theater’s historic sources, the freestanding colonnade that marks the amphitheater’s presence adds an appropriate classical touch. This outdoor facility is one of several recently constructed in Louisiana that are sited to take advantage of views across a river or waterway and, consequently, offer an opportunity to reflect on the centrality of rivers to the state’s history and beauty, while enjoying a musical performance.

Another example is in downtown Gretna, where a newly built amphitheater on a section of the levee offers spectacular views of New Orleans across the Mississippi River. This structure, which is steeply stepped with concrete benches, is linear, not curved, as it follows the levee’s bank.

Some open-air amphitheaters have been incorporated into a public park to add to its attractions. Such is the case of the one in Jambalaya Park in the city of Gonzales, which was built to provide a setting for informal concerts and other community events. The semicircle of stepped seats facing the stage is defined and partially shaded by a row of trees. At Lake Charles, the amphitheater at the south end of the Civic Center grounds beside the lake is formed of a grassy gentle slope, making it like the earliest of Greek theaters that lacked built-in stepped benches. The stage is sheltered beneath a pavilion. This modernized version of a bandshell, designed by architect Randy M. Goodloe, is formed of a triangular-shaped trussed roof balanced on two massive brick-faced columns and a rear backdrop with side wings to direct sound outward to the audience.

The large and rather magnificent open-air riverfront amphitheater built for the Louisiana World Exposition of 1984 was, unfortunately, demolished after the fair closed. If it had survived, it would have given New Orleans a structure by a then-emerging but now world-famous architect, Frank Gehry. Today he is best known for his titanium-covered museum of 1997 in Bilbao, Spain and the similarly free-form design for the Walt Disney Concert Hall of 2003 in Los Angeles. Gehry’s amphitheater in New Orleans, which overlooked the Mississippi River, was twelve stories tall and could seat 5,400 people. As the main entertainment stage for the fair, it hosted many famous musicians and entertainers. Gehry’s initial scheme for the building was for a roof composed of glass fishscales, but that was deemed too costly and a cheaper corrugated metal roof was substituted instead, which, as it happened, reflected the architect’s then-use of everyday materials in his designs. After the fair, efforts were made to save the theater, but for several reasons, that was not to be. For those wishing to see a free-form Gehry-designed building (though not an amphitheater) that is not too far away, the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art in Biloxi, Mississippi, is a small version of the Bilbao and Los Angeles structures.

As more towns and cities in Louisiana redevelop their riverfronts or lakesides for public enjoyment, perhaps they, too, will build Greek theaters. If so, they will be drawing on a long and venerable tradition, and one that is now also a Louisiana tradition.

—–

Karen Kingsley, Ph.D., is professor emerita of architecture at Tulane University, author of Buildings of Louisiana (Oxford University Press, 2003), and editor-in-chief of the Buildings of the United States series.