The Rost Home Colony

The rise and fall of a Reconstruction experiment

Published: May 31, 2023

Last Updated: August 31, 2023

River Road Historical Society

Destrehan Plantation ca. 1865.

During the Civil War and after, the Army and the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands (or Freedmen’s Bureau) attempted to steward the South from a forced-labor economy to a free-labor one. According to their designer, Thomas W. Conway, the Rost Home Colony and its three counterparts in Louisiana, the Bragg, Sparks, and McHatton Home Colonies, were crucial to that mission. In Conway’s vision, the home colonies were meant to solve an uncomfortable question now raised in the postwar South: In a free-labor economy, how will society account for parentless children, the old, the infirm, and the sick? In Conway’s own words, the home colonies were “to provide a place of refuge and a home for the aged and helpless freedmen, thrown upon the Bureau for support.”

In the postwar South, there were few options for relief. The war had disrupted families and extended kin networks and ravaged the finances of almost every institution, especially local and state governments. Black people, most of whom had been enslaved just years before, struggled to provide for themselves and their immediate relations in a difficult economy. In Louisiana, as in other war-ravaged places in the South, Black women, men, and children became refugees as they left plantations for Union lines. Black benevolence societies were still decades away. Former enslavers had no desire to provide for the destitute Black people who had broken their bodies during slavery or in the war to end it. Before emancipation, enslavers were theoretically responsible for enslaved people’s care, not the government. Most of the time, however, communities of enslaved people bore the brunt of the burden of caring for their elders and for the sick and injured. Since most Southern state governments were in rebellion in the mid-1860s, the US Army assumed responsibility for these problems during the Civil War. As one Freedmen’s Bureau official in Louisiana wrote in 1866, “The civil authorities throughout the state seem to take very little or no interest in the sick and destitute among the freedmen.”

In a free-labor economy, how will society account for parentless children, the old, the infirm, and the sick?

Enter Thomas Conway. A Baptist preacher-turned-army chaplain-turned-bureaucrat, Conway created home colonies to confront those social and economic problems brought on by the war, providing shelter for disabled, sick, and aged formerly enslaved people. Plantations abandoned by enslavers (McHatton fled to Texas, then Mexico, and finally started a new sugar plantation in Cuba) or once owned by rebels (Rost was a Confederate minister to Spain; Bragg fought as a Confederate general) were perfect sites to enact his experiment. The government provided colony residents with necessities and services, like food, clothing, medical care, and education, in exchange for the proceeds of whatever labor it could muster from the residents. The home colonies were to be self-sufficient. As Conway wrote in 1865, “It has been determined not to allow the work of caring for the freedmen . . . to be of any expense whatever to the United States.” If the colonies succeeded, they perhaps might even produce surpluses that the government could use to fund other benevolence programs. Impressed, Skinner titled his chapter on Rost Home “Beneficent Bureaucrats.”

As a result, the US government forced these newly freed people—the disabled and elderly—to labor. Conway assured his superiors that these colonies were not sheltering the lazy, restful, or vagrant—vagrancy being the bugaboo of the Reconstruction-era South. After establishing a new colony on the former plantation of Daniel P. Sparks in Jefferson Parish, Conway wrote that he “desired to impress upon the minds of all who came into my charge that work could in no case be avoided, and if they fell upon the Government to be maintained, they must work as hard as if” they worked on a private plantation. He further repeated in his report of 1865 that, at the home colonies, “labor is forced, and none can avoid it,” except for the sick. Such policies, Conway thought, had “been instrumental in decreasing the number of vagrants who would otherwise have crowded upon me.” He even touted the colonies as the best deterrent to vagrancy. Most would-be vagrants, he assumed, would rather work for former enslavers for a wage than for rations on a federally operated home colony. Such were the realities of “free” labor sanctioned by the US government in the postwar South.

When Skinner arrived at the Rost Home Colony in 1865, the Bureau had already replicated the experiment in government-run poor relief and forced labor elsewhere in Louisiana and was poised to export it to other southern states. If Conway had his way, each post of the newly organized Freedmen’s Bureau would have a home colony in its jurisdiction. In addition to the four already in Louisiana, plans were also underway to establish a colony near Monroe, Louisiana, as well as a handful in Alabama. At the dawn of Reconstruction, home colonies appeared as though they might become ubiquitous in the South.

Little has survived to provide insights on life in the home colonies. There are no surviving accounts of home colonies produced by freed people who lived on them. The only sources that provide glimpses into Black people’s lives are a handful of letters and telegrams from the officers in charge and a collection of registers from the Rost Home and McHatton Home colonies. At first, most of the people at Rost Home had lived on the property before and during the Civil War; they were people who’d been enslaved by Pierre Rost. Over time, others arrived and some left, the comings and goings meticulously recorded by the government officials stationed there. Since the Freedmen’s Bureau recorded first and last names, it appears that formerly enslaved people often came as families. Marie Annette came to Rost in March 1865 from St. James Parish, bringing her four children; a month later, Eli and Rena Butler, a young and sickly married couple, arrived from Amite County, Mississippi. By July 1865 Conway reported that six hundred freed people lived at the Rost Home Colony.

Gathering people who were unable to work onto a farm and banking that their collective productivity would support their own expenses turned out to be a fool’s errand.

There were compelling reasons for freed people to choose to live at a home colony (not all residents of the home colony were there by choice; some had been charged with “vagrancy” and redirected there in lieu of jail or chain gangs). Perhaps most compelling were the colonies’ operators, who were officers of the US Army. It appeared to Skinner that the residents of Rost Home “reposed great confidence in government officials, and were willing to work hard when they felt sure of being paid.” When the alternative was a former enslaver willing to breach labor contracts, a government-run plantation may have been preferable. Though white officers ran the colonies, Black soldiers were often stationed there; a sergeant’s guard of the 96th United States Colored Troops manned the Rost Home Colony. This biracial military presence may have afforded residents of the colonies some protection against racial violence. Doctors and teachers also lived on home colonies, meaning the residents had access to services rare elsewhere in rural Louisiana. The Rost Home Colony was home to one of three Freedmen’s Hospitals in the state—institutions run by the Freedmen’s Bureau and manned by army doctors. Two white female teachers lived at the McHatton colony in the fall of 1865, according to the military doctor posted there. There was also the promise of government rations, even if paltry.

Of course, there were also compelling reasons to avoid home colonies if possible. Work was compulsory unless people were sick. Rations were often sparse and of low quality. The government used rations to compel labor. An employee of the Treasury Department advised Conway to govern Rost Home by the maxim “he that will not work neither should he eat.” Residents were not always allowed to leave the colony once they arrived. The registers of arrivals and departures at Rost and McHatton Homes suggest that people needed to provide evidence of future employment in order to get off the plantations—another manifestation of the Reconstruction-era obsession with the specter of “vagrancy.”

None of the home colonies lasted longer than eighteen months. The colonies’ demise was part practical and part political. On the one hand, they were never self-sufficient. Government loans and rations kept the colonies afloat. Gathering people who were unable to work onto a farm and banking that their collective productivity would support their own expenses turned out to be a fool’s errand. At Rost in July 1865, the labor of 227 people supported 600, with a quarter of the population sick or unable to work. At McHatton and Bragg, the proportion of sick was even larger, near 40 percent. Crop failures and bad harvests in 1865 and 1866 made the situation worse. Only the Rost Home Colony ever made money, and even then only in its final year.

Conway also lost political battles. First the government reduced his jurisdiction from Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas to just Louisiana when he started a position in the Freedmen’s Bureau in the summer of 1865. Meanwhile Andrew Johnson’s succession of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 ushered in a presidential administration less keen on establishing freed people’s rights or considering their economic well-being. Allies of Johnson in the Freedmen’s Bureau conspired against Conway and other colleagues to end policies seen as favorable to Black people. In early October 1865, New Orleans newspapers reported Conway’s dismissal and his temporary replacement by Johnson-accolade James S. Fullerton. Once Conway’s days were numbered, so too were the home colonies.

By the end of 1865, “for reason of economy,” according to a special order from Fullerton, the government closed the Bragg, McHatton, and Sparks Home Colonies and transferred the sick and infirm to the Rost Home Colony. The plantations were soon returned to their owners. Even Rost was able to return to his plantation in St. Charles Parish, and the US government paid him rent to continue the colony there, through 1866. In his yearly report for 1867, the latest Freedmen’s Bureau assistant commissioner for Louisiana reported the closure of the Rost Home Colony, with “the greater portion of the aged, infirm, and helpless . . . sent to the Freedmen’s Hospital” in New Orleans.

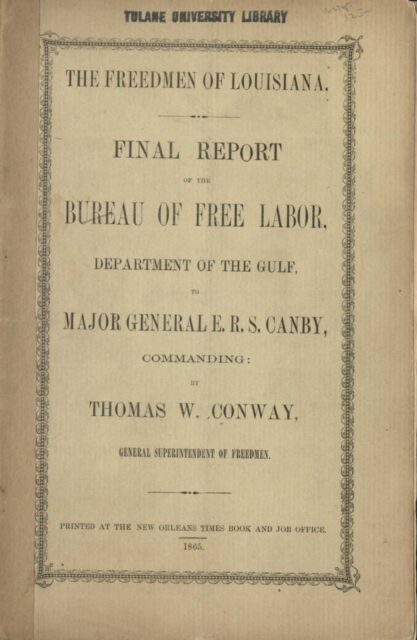

Cover of Conway’s final report to his commanding officer. Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University.

In its final year the Rost Home Colony had made $14,150 from its cotton and sugar crops. The Bureau purchased bonds with that money and used the interest to support teachers at orphanages for Black children in New Orleans. In its final year the Rost Home Colony had realized Conway’s dream that a self-sustaining, government-run farm for the sick, the old, the infirm, and the so-called vagrant could fund other benevolence programs. By then the Freedmen’s Bureau in Louisiana was retreating from poor relief; in August 1867 it had stopped distributing rations to parish offices and only sent people to the New Orleans hospital for refuge. As historian Jim Downs writes in Sick from Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction (2012), attempts at government-sponsored poor relief like the Rost Home Colony failed because “the federal government viewed its role as temporary, feared that these institutions would encourage dependency, and wanted state and municipal authorities to eventually take responsibility.” Even the colony’s invested money was unsafe. In the 1870s an employee of the Freedmen’s Bank in New Orleans embezzled the funds—perhaps hoping that no one would notice missing bonds credited to a defunct government experiment.

The Rost Home Colony became a footnote to the long, violent, and complicated history of Reconstruction in Louisiana. On the one hand, the home colonies represented an attempt by the federal government to alleviate Black people’s suffering in an era when inaction was often the default response. On the other hand, the colonies embodied an irony of “free labor”—though intended as benevolence projects, home colonies were coercive, restricting the movement of residents and forcing them to labor without financial compensation, in exchange for rations.

And then there was the matter of the heart behind the benevolence itself. Let the newspaper editors of the Black-run New Orleans Tribune have the last word on Conway—a man they knew and with whom they often found common cause: “Philanthropists are sometimes a strange class of people,” they wrote of Conway in August 1865. “They love their fellow men, but [in their estimation]. . . these fellow men, to be worthy of their assistance, must be of an inferior kind.”

Destrehan Plantation has recently installed an exhibit on the Rost Home Colony in the Haydel-Miller Museum on the property grounds. Admission is included with tickets to the plantation.

William D. Jones is the historian of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. He earned his PhD from Rice’s history department, where he wrote a dissertation on survivors of the nineteenth-century slave trade to Louisiana. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Louisiana State University Libraries, and the Louisiana Historical Association have supported his research.