Widow’s Mite

Freedwoman Eliza Dorsey’s struggle for a Civil War pension

Published: May 31, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

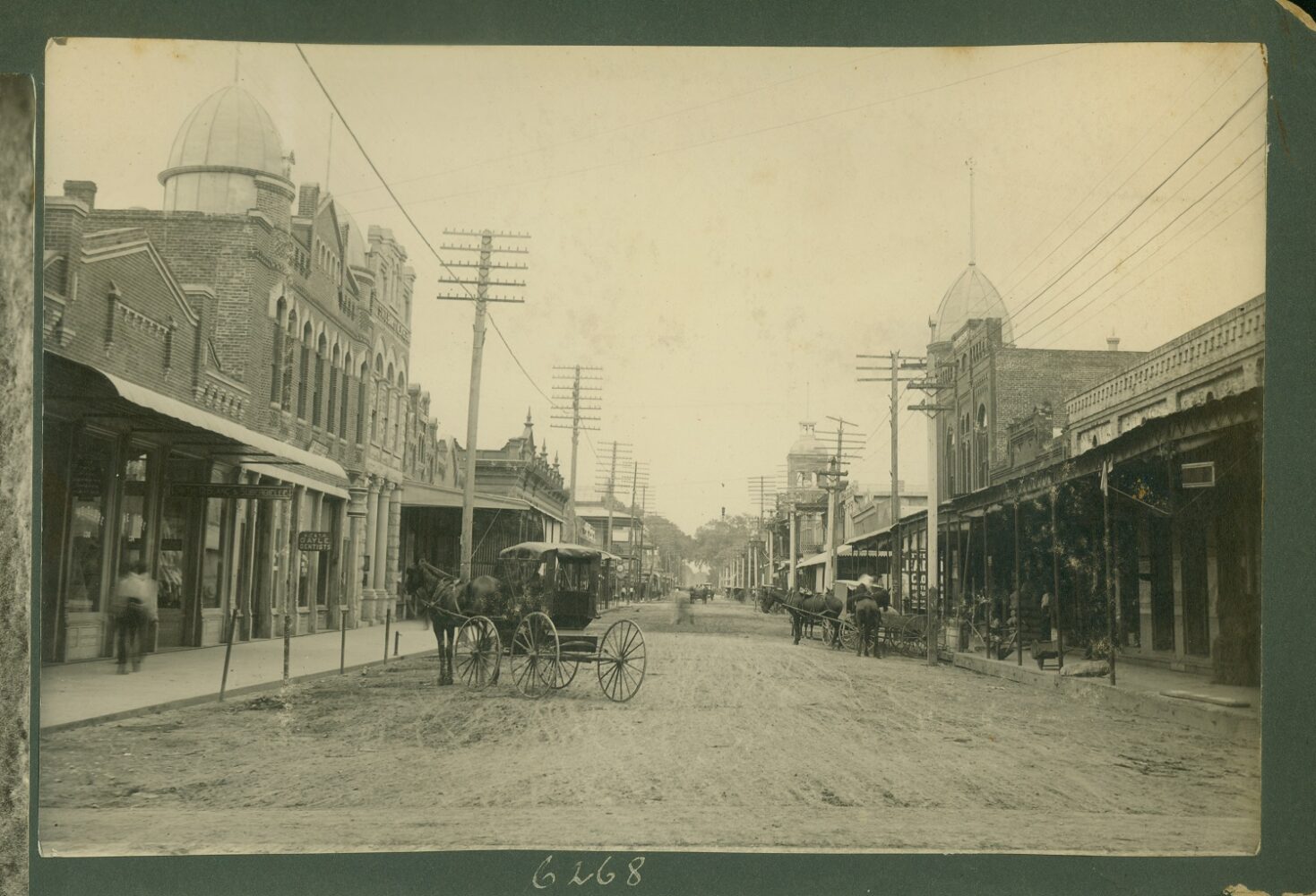

Photo by Andrew D. Lytle, Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University

New Iberia, ca. 1900.

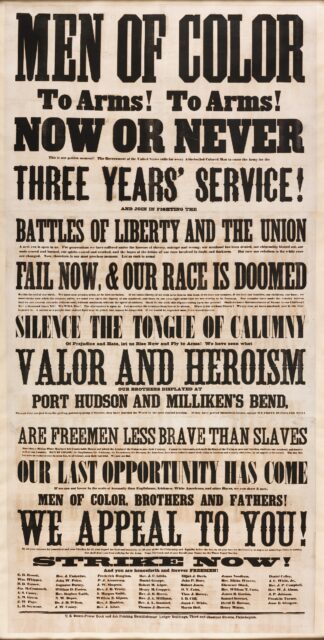

Dorsey wrote on the pension application that she and Bray were married almost fifty years earlier, in New Iberia in 1862. The two were enslaved when they were married, but a year after their marriage, Union troops marched into the plantation region lining the Bayou Teche and liberated them. Shortly after, Bray joined the 93rd United States Colored Troops. He was one of the twenty-four thousand formerly enslaved men from Louisiana who joined the United States Army during the Civil War, the most Black volunteers of any state in the country.

Fitch’s investigation of Dorsey and Bray’s marriage opens a window into Black people’s lives in Louisiana before and after the Civil War and illustrates how the federal government created and perpetuated institutional barriers that prevented Black citizens from receiving equal treatment, even those who had fought and died for the Union.

Dorsey’s 1911 application was standard. A 1901 law allowed widows who remarried after their first husband’s death to receive a pension, so there was no mystery to her filing an application fifty years after the Civil War. However, when bureaucrats at the agency received her application and began to investigate the records they had on Houston Bray, they found that the Bureau had already fulfilled an application from Bray’s widow. Her name, according to the application, was Mary Joseph, not Eliza Dorsey. Complicating matters further: Joseph had died in 1868.

Mary Joseph said, in an affidavit taken down in 1867, that she and Houston Bray married sometime in 1855 on a Decuir plantation somewhere in Louisiana. They had two children: Harry, born in 1857, and Catherine, born in 1860. After Bray enlisted in the US Army, an army officer in New Orleans formalized their marriage, per a marriage certificate dated June 26, 1865. Friends and acquaintances of Joseph, including two women who said they helped her give birth, signed affidavits attesting to her marriage and to her children’s parentage.

This broadside exhorted Black men to enlist in the Union army. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Someone had committed fraud. At least that was special examiner Fitch’s presumption when he left his office in room G of the US Customs House in New Orleans for New Iberia in the summer of 1911. In this case, everyone involved was Black, which may have further increased Fitch’s suspicions. On rating indexes that accompanied every report, Pension Bureau special examiners listed the names of the people they deposed and rated their reputations. These ratings were qualitative, using words like fair, good, or not reliable, and they appeared on the indexes that examiners created of their reports. They estimated Black and poor people’s reputations as “fair” or unreliable most often, and they usually marked wealthy and white people as individuals with good reputations.

After his arrival in New Iberia in late July, Fitch made his way to Dorsey’s house at 532 Lafayette Street and notified her of the investigation. In the coming weeks, Fitch traveled around the Teche region looking for people who knew Houston Bray or Mary Joseph. First, he gathered depositions in New Iberia, beginning with someone who knew Houston Bray well: Samuel Brown. Brown had served in the same regiment as Bray during the war, and they both worked at Jasper Gaul’s sawmill in New Iberia as enslaved men before emancipation. In 1858, according to Brown, Gaul hired Houston Bray from his enslaver, a man named Joe Rawles who lived on Bayou Courtableau in St. Landry Parish. Under this arrangement, Gaul paid Rawles a monthly fee while Bray worked for him. Brown never heard that Bray was married to anyone but Eliza Dorsey. “If Houston Bray had a wife and children before the war,” Brown concluded in his deposition to Fitch in late July 1911, “he must have had them before he came to work at the sawmill.”

Mary Joseph’s name was news to Eliza Dorsey also. Dorsey’s story of her marriage to Bray made no mention of Bray’s previous marriage to Mary Joseph. When Dorsey met Bray, he worked at Jasper Gaul’s sawmill on the west end of town. They courted for a time—he visited her on Saturdays and Wednesdays—and they married and began to live together around 1860 or 1861. After Bray joined the Union army, in 1863, Dorsey didn’t see him much. “It was not very safe for a colored soldier to go very far from his regiment or camp with his uniform on. Some Confederate sharpshooter might have taken a shot at him,” Dorsey said in her deposition on July 26, 1911. When Fitch pressed Dorsey for any knowledge of Mary Joseph, in a second interview on August 16, the widow exclaimed: “I never heard of that Joseph woman in my life, until the day my initial statement was taken. I never heard Houston Bray speak of having lived on Bayou Courtableau or about Opelousas or anywhere in St. Landry Parish.”

After spending a week or so in New Iberia asking formerly enslaved people and former enslavers about Houston Bray, Fitch found no one who had heard of Mary Joseph. Even Louis Victor Barthe, whose grandmother enslaved Dorsey, corroborated the widow’s story. As Samuel Brown said, if Houston Bray was married to Mary Joseph, they must have married before Bray began to work at Gaul’s sawmill in New Iberia. Fitch started to investigate this theory. If true, it explained Mary Joseph’s already approved pension application from 1867, which claimed she had married Bray around 1855 on the Decuir plantation—around three years before Bray arrived in New Iberia. All Fitch had to do was go to St. Landry Parish, find the Decuir plantation, and find people who knew Mary Joseph.

That task proved difficult. The roads were muddy and traveling from New Iberia to places in St. Landry was sometimes impossible. Fitch was able to procure the testimony of Ann Lewis from Arnaudville in St. Landry, who was Houston Bray’s cousin. She had never heard of Bray being married; she had never heard of Mary Joseph; and she had never heard of a Decuir family in the area. Lewis even said Bray had never lived in St. Landry. The investigator’s search for Houston Bray’s life on a Decuir plantation, where he supposedly married Mary Joseph, ended inconclusively.

He was one of the twenty-four thousand formerly enslaved men from Louisiana who joined the United States Army … the most Black volunteers of any state in the country.

Fitch’s failure to square Mary Joseph’s and Eliza Dorsey’s stories did not stop the Pension Bureau from making a decision about Dorsey’s pension claim. By August 30, 1911, Fitch was back in his office in New Orleans writing a summation of his investigation to the Commissioner of Pensions. In September, the chief of the law division at the bureau read Fitch’s report and crafted a recommendation. He argued that Eliza Dorsey should not receive a pension. He conceded that Dorsey had a relationship with Bray, but he did not think that Mary Joseph’s claims were false either. Since Bray was hired out by his enslaver, “he evidently had great latitude in the periods of his recreation and he probably did cohabit with the claimant.” But, if Mary Joseph’s story was true, and Bray’s “master never consented to the dissolution of his relation to [his] wife,” then Bray had committed adultery. Moreover, the bureaucrat reasoned, since Bray and Joseph were formally married in 1865—a fact proven by a written document that the official was inclined to trust— “there can be no valid reason for assuming that his relation, if any, with Eliza was anything more than concubinage.” He declined Dorsey’s claim.

Fitch found no evidence, while conducting his fieldwork, to back up the written record. When he asked people who knew Bray in Attakapas about Joseph, no one knew her. If Joseph lied, though, what was the truth?

A seventy-five-year-old United States Colored Troops veteran named Isaac Rose may have told special examiner Fitch exactly what happened when he sat in front of the investigator on August 23, 1911, in Algiers. Rose lived near Bayou Sara before the Civil War, “until the Yankees came into the country when I followed General Banks and his army to New Orleans.” Rose was one of thousands of freed people who followed the Union Army into the city. During the war, he met a woman named Nicey Rawles. “[H]er owner was J. B. Rawles and she came from Attakapas,” he remembered. She had a brother named Houston who died in the army and left a wife, named Mary. According to Rose, Mary “took up with Houston in the army and married him in the army.” Rose didn’t know where she was from, and he didn’t remember her children, but he remembered that Mary died a few years after the war. He even remembered that he went to her funeral.

If we believe Rose, a different story about Houston Bray emerges. Perhaps Bray was married to Eliza Dorsey before the war, but things changed after he enlisted. As Dorsey said, she never saw Bray after he joined the army, even when his regiment was still in New Iberia. After transferring to New Orleans, Bray met Mary Joseph, a single mother of two. They married before his departure from the city with the army during the war’s final days in 1865. Two years after Bray died in the army, Mary filed her pension application. To ensure the government accepted her application, and to ensure she provided for her children, she lied. She didn’t make up her marriage to Bray, but she said her relationship with him began long before it did. In fact, she made sure to state that it began years before the war, and before the births of her two children, then ten and seven years old. By claiming that Bray was her children’s father, Mary might have reasoned, her son Harry and daughter Catherine would receive Bray’s pension if she died. She found sympathetic friends willing to testify that these facts were true, submitted the pension application in 1866, and banked on no one in the Pension Bureau—then flooded with pension applications from soldiers, widows, and children—bothering to check.

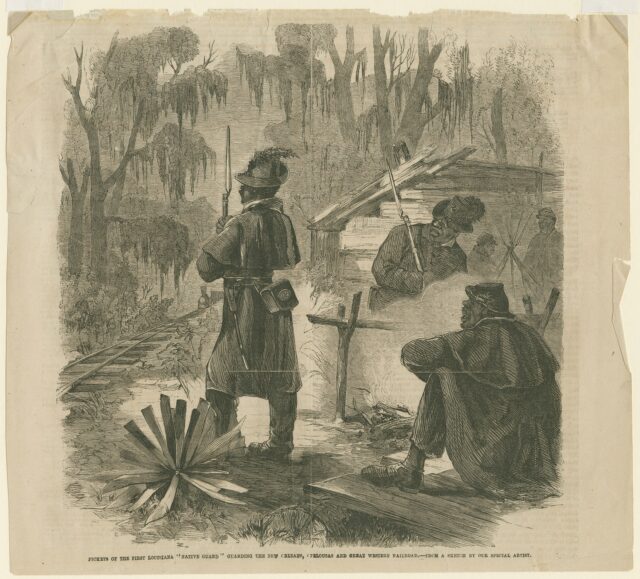

An 1863 engraving from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper shows a Black Union Army unit guarding the New Orleans, Opelousas and Great Western Railroad. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

No one did check, and when Mary died less than two years after she submitted her application, her children Harry and Catherine received her pension through their legal guardian until they each turned sixteen. In 1911, Fitch never determined what happened to the Bray children. He never found them.

Unfortunately for Dorsey, Fitch never gave Isaac Rose’s story, or the possibility that Houston Bray met and married Mary Joseph after he married Eliza Dorsey, much credence. Fitch told his superiors that he had to ask Rose leading questions to jog the old man’s memory, “always an objectionable method of examining a colored witness if it be desired to find out what he actually knows,” Fitch stated as a matter of fact. According to the investigator, “After a little time if encouraged to go on and state something in his own way, he would make the most astounding contradictions and mix things up.” As Fitch wrote of Rose in his letter to the Pension Bureau’s chief law officer: “I decided that he was ‘nutty.’”

The investigator’s racism, which precluded fair analysis of the depositions he collected, only exacerbated the difficulty of attempting to prove an undocumented marriage that occurred between two enslaved people half a century earlier. As Fitch wrote in his final report to the Commissioner of Pensions on August 30, 1911: “I have rated many of the witnesses fair owing to their ignorance and stupidity, but I believe that they honestly endeavored to tell the truth.” When Black people told the truth, Fitch reduced their stories to fables. Even if Fitch had undertaken the investigation with an egalitarian mind, the Pension Bureau still had little desire to admit past failings and fulfill two pensions for one soldier. Dorsey had all the cards stacked against her.

So, on September 25, 1911, after an in-depth investigation fraught by racism, Eliza Dorsey received the following letter from the Commissioner of the Pension Bureau: “Madam: Your above entitled claim for pension under the general law, filed March 1, 1911, is rejected on the ground that the best obtainable evidence fails to show that you were ever the lawful wife or widow of the soldier. Very respectfully, Commissioner.”

William Jones is the Postdoctoral Research Associate in Slavery, Segregation, and Racial Injustice at Rice University and the historian of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. He earned his PhD from Rice’s history department, where he wrote a dissertation on survivors of the nineteenth-century slave trade to Louisiana. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Louisiana State University Libraries, and the Louisiana Historical Association have supported his research. Jones is a graduate of Tulane University.