Coastal

Treading Water

A local reflects on St. Bernard Parish’s generations-long struggle to stay afloat

Published: March 1, 2019

Last Updated: June 12, 2023

Photo by Monique Verdin

Monique Verdin’s grandmother, Armantine Verdin, at their family home after Hurricane Katrina.

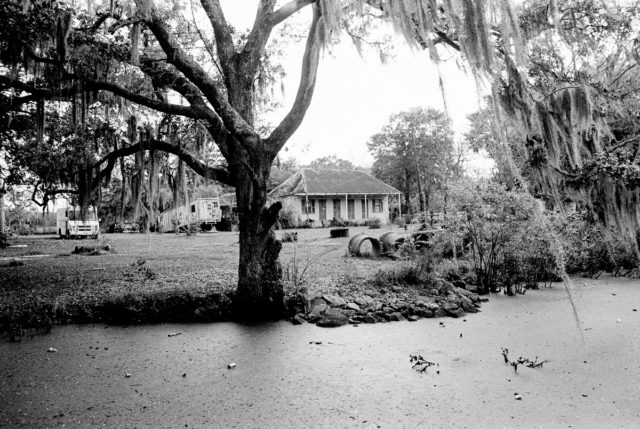

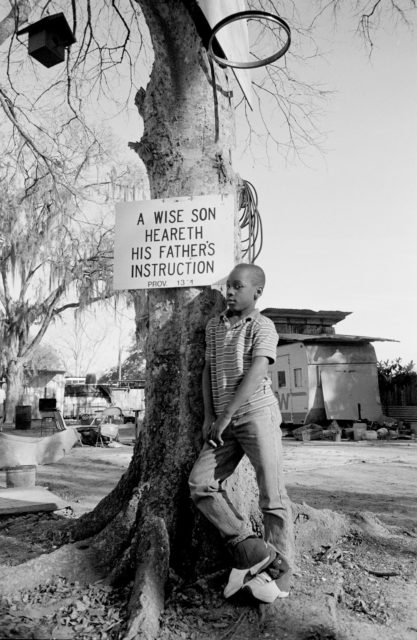

I live on the high ground along the old Bayou Terre aux Boeufs ridge, just inside the “Great Wall of St. Bernard,” a nearly thirty-foot federal risk-reduction levee the Army Corps of Engineers calls the Chalmette Loop. My home in Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta is not far from the forgotten southern bayou settlements of Yscloskey, where the ancient ones built earthen mounds and middens; St. Malo, where Maroons and later Filipinos found a sense of freedom; La Concepción, where Canary Islanders defended colonial claims; and the island of Delacroix, where many of their descendants, known as “Los Isleños,” retreated. All these places lie within the boundaries of the parish of St. Bernard, just southeast of a territory the Choctaw called Bulbancha (“place where many languages are spoken”), where the 300-year-old colonial port city of New Orleans now sits.

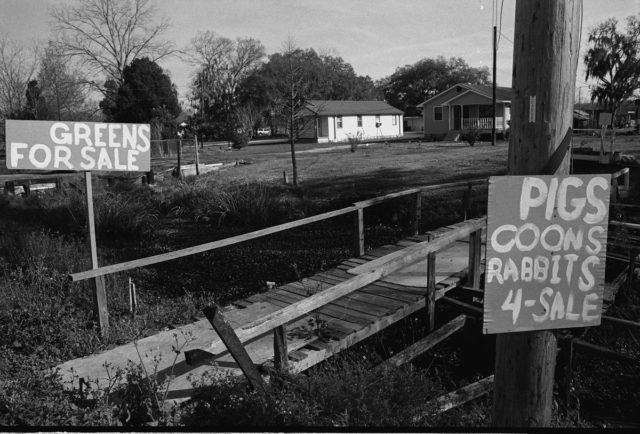

My Native American grandparents migrated to St. Bernard in the late 1930s with a small band of Houma relatives in search of a better life. They worked as trappers, hunting mink, muskrat, and otter during the end of Louisiana’s fur-producing heyday, at a time when the oil and gas boom in the wetlands had begun to redefine the economic and environmental landscape and ways of life in the Mississippi River Delta. Moving to St. Bernard allowed them to find a path out of the oppressive discrimination they were forced to endure in Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes, where land rights had been stolen, equal rights to education were limited, and their right to vote was denied. After years of trapping in the winters and my grandfather working for the parish as a laborer in the summers, they were able to buy a little piece of paradise on delta soils next to Bayou Terre aux Boeufs, where they built a house, planted a garden, and raised a family. Their homestead is the place I now call home.

For thousands of years before the present era, Bayou Terre aux Boeufs and Bayou la Loutre were part of the dynamic delta system diverting freshwaters and sediments south to the sea, building what we now know as the St. Bernard delta lobe. Terre aux Boeufs translates to “land of cattle.” Colonial-era Jesuits described wild bison roaming the lands that bordered the old waterway. The bison were hunted into extinction during the early years of colonial conquest; however, seeds carried on their hides from the northwest hundreds of years ago continue to grow evidence of their southeastern migrations, visible in pockets of remnant prairie hidden between bottomland hardwood forests on slivers of high ground hugging the banks. Most of the ancient forests were clear-cut for plantations to cultivate indigo, cotton, and sugarcane, and manmade levees were constructed along the river to protect these crops from floodwaters, severing natural distributaries of the Mississippi River from their headwaters. Today, Bayou Terre aux Boeufs sits stagnant in my front yard and is used primarily as a drainage canal, maintained by parish workers spraying poison to kill all vegetation growing on its banks. Down the road, outside of the risk-reduction levee, tidal flow from the estuaries moves water in and out with the cycle of the moon or the winds, pushing water from the bayou to the lakes and bays and back and forth to meet the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1922, just a few miles up the road from my home, the river burst through the manmade levee in Poydras near the old headwaters of the Terre aux Boeufs where the bayou has been disconnected from the main channel, creating a crevasse that flooded all of eastern St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes. Five years later, during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, a group of bankers and prominent businessmen convinced state officials to dynamite the levees about a mile south of Poydras to “save New Orleans,” again flooding all of St. Bernard Parish. City officials promised reparations to St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parish residents, but their promises turned out to be largely empty. Of the more than $12.5 million in eligible claims (not counting an additional $25 million deemed ineligible), the city paid out only $2.9 million. After deducting a million for sheltering and feeding those left homeless by the man-made flood and paying out $1.5 million to a single company tied to the New Orleans cabal, some residents received an average payout of $274, a pittance, but thousands were never reimbursed for their losses. The choice to sacrifice the parish to save the city has left an unforgettable mark on the consciousness of generations of parish residents, who understand how the promise of compensation can be so quickly forgotten. This legacy continues to resonate for those who have lived through the twentieth century’s cycle of tropical storms, from Hurricane Betsy in 1965 to the levee failures during Hurricane Katrina forty years later. In January 2019, the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal by landowners of St. Bernard and Orleans Parishes seeking compensation for 2005–2008 flood damages caused by the Army Corps of Engineers failure to maintain the federal Mississippi River Gulf Outlet. This decision granted the government immunity from the failure of flood control projects.

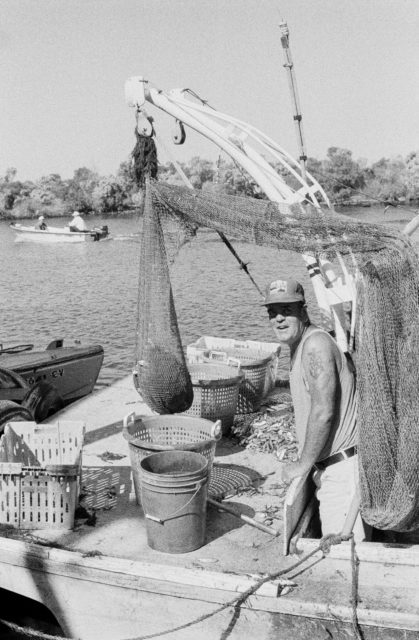

In 1991, the Army Corps of Engineers completed a freshwater diversion along the Mississippi, reconnecting fresh river water to the wetlands, designed to balance basin salinities for oyster production. The St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parish line at Caernarvon, the same community where the levee was blown in 1927, was the chosen site for the project. After almost thirty years in operation, scientists report positive results: land accumulating, trees growing, and salinities stabilizing. Some fishermen disagree, saying the diversion allows saltwater further inland whenever a storm surge pushes in and claiming too much freshwater makes it harder for them to catch seafood for market. Descendants of those who survived the 1927 flood and other residents of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Lafourche, and Jefferson Parishes anxiously await the unknown side effects of what thousands and thousands of cubic feet per second of river water being introduced into the environment will do once the Mid-Breton and Mid-Barataria sediment diversions become operational. The hope is that diverting sediment and fresh water from the Mississippi River to the surrounding marshland—a process that could begin as early as 2025—will help curtail land loss. The fear is that the unprecedented projects will inundate fishing grounds with too much freshwater, killing production in estuaries and leaving low-lying communities more vulnerable than they are already. Fishermen have begun to argue that the Mississippi’s waters are too polluted (they are known to create dead zones offshore) and advocate that dredging sediment to build back barrier islands and interior marshes should be prioritized before the construction of what they consider experimental sediment diversions, even though a dredge-only approach is an expensive and unsustainable quick fix.I’ve heard fishermen tell coastal scientists: “You may have a degree, but I’ve been watching the marsh all my life.” Fishermen intimately understand the wild ways of the wetlands, because they are a part of this ecosystem and love it as they love their own families. And they are willing to fight for what they love, especially if home and livelihoods are on the line. At this critical time in our coastal history, it is important for an intersectional and diverse spectrum of expertise, spanning local knowledge to coastal science, to be included in the planning process. The State of Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), the agency tasked with executing the Coastal Master Plan, has attempted to build those bridges and likes to remind us that “there are many tools in the toolbox” needed for the south Louisiana coast to survive, including the restoration of oyster reefs, barrier islands, headlands, ridges, and hydrology, in addition to marsh creation and the reconnection of the river to the wetlands.

During the 2017 Coastal Master Plan public comment meetings, officials stated that the worst-case scenarios of coastal land loss predicted in the 2012 plan had become the best-case scenarios in the 2017 plan because the sea level is rising more rapidly than projected. According to CPRA literature, if no restoration were to occur in the next 50 years St. Bernard could lose up to 72% of its land. Dire warnings throughout the plan are tied to “Future Without Action” scenarios and solutions tiered under three categories: structural, meaning hard infrastructure like levees; nonstructural, which refers to efforts involving coastal structures, including flood-proofing business, elevating homes, and buying out hard-to-protect properties; and restoration, including projects like barrier island or marsh creation.

Modern conditions across the coast can be compared to the medieval system of fortification-based security. We like to believe that if you are inside the walls you are safe, if you are outside you are on your own, but it’s not as simple as we imagine. Living inside levee risk-reduction systems comes with the benefit of more affordable home insurance, but it does not come without a fair share of risks and uncertainties. Homes may not flood as often on the inside, but levee walls are never foolproof— they call them “risk-reduction” as opposed to protection levees. Tropical storms are more frequent and seem to be intensifying, and there are seen and unseen dangers that come with living surrounded by a web of petrochemical pipelines and refineries, even if the benefits of jobs and resources for restoration are tied to the industry.Louisiana’s reliance on petroleum extraction carries many risks, with oil spills always possible and often real. The irony of the black tide nightmare, when sweet crude stained the Gulf of Mexico and saturated our coast during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, is that the disaster became a catalyst to bring real dollars to the state for the execution of coastal restoration. Three major one-time funding streams for Louisiana coastal restoration resulting from the oil spill and subsequent legal settlements will be paid out over the next fifteen years: a $5 billion National Resource Damage assessment, roughly $1.3 billion in criminal penalties, and roughly $1 billion in federal RESTORE Act funds. Each funding stream comes with its own specific rules for how the money can be spent.

As decision-makers in the Trump administration roll back offshore drilling safety regulations implemented after the Deepwater Horizon drilling disaster, I cannot forget how my family and friends signed on to work in BP’s Vessels of Opportunity program to help with the hazardous material cleanup. The scene was surreal: fishermen loading oil booms onto boats instead of fishing nets. This went on for months. Knowing that we continue to gamble with the fragile balance of our ecosystem, exploring for fossil fuels in deeper waters than ever before, I fear what is on the horizon if we don’t begin to think of other energy alternatives and more sustainable ways to finance the restoration of our coast.

Not tied directly to the oil spill but similarly ironic, GOMESA, the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act, allocates federal deep-water oil and gas royalties back to the Gulf states, which Louisiana in turn uses as a major funding stream for coastal restoration efforts. Louisiana at one time projected receiving close to $140 million annually from GOMESA; however, the state only received $82.8 million for the 2018 fiscal year, with $66.3 million going directly to CPRA for coastal restoration and protection efforts and the other funds trickling out to the twenty coastal parishes. Long-term funding from GOMESA is uncertain due to drops in oil prices, downturns in offshore production, and presidential threats to reallocate royalties away from the Gulf states and back to the general treasury. Climate change and sea-level rise are caused by the burning of fossil fuels, yet the restoration of the coast of south Louisiana is dependent upon finances coming from the extraction of fossil fuels into the infinite future at the highest production rate possible.

We will never be able to design solutions as well as nature, especially if we are not willing to accept the fact that this dynamic delta is in a constant state of redefining its ever-changing water-made landscape. We have inherited this hyper-managed system and as we attempt to restore it, we are only trying to mimic the natural intelligence of this place we call the Mississippi River Delta. It’s complicated and overwhelming to think about land being lost at one of the fastest rates in the world, especially if that land is a place you call home, but it is important for us to keep talking about it, to face the challenges, to analyze past mistakes, and to weed out contradictory solutions in order for us to dream and continue to work towards building the sustainable future our coastal south Louisiana deserves.

In spite of all the challenges, I am excited about a number of coastal projects happening in my own community. The Breton Ridge Restorations of Bayous la Loutre and Terre aux Boeufs; the living shorelines and world-class oyster reefs being installed in our estuaries; marsh creation in the Golden Triangle, Central Wetlands, Breton Basin, and Lake Borgne; mangroves being planted by our Chalmette High 4-H youth; and the new Nunez Community College coastal workforce development program all give hope for the future. But I still can’t help wonder if we are out of time.

Over the years we have heard whispers that not all communities across the coast will be able to be saved, that some will have to be sacrificed to the rising waters. Some of those places, left outside levee risk-reduction systems, are now being identified by name. One such place is Isle de Jean Charles in Terrebonne Parish, where some of my ancestors once lived. The island has witnessed 98 percent land loss since 1955. What was once an island of 22,400 acres now encompasses only 320 acres. Isle de Jean Charles was recently awarded $48 million dollars from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s National Disaster Resilience fund for the first federal resettlement program addressing climate change. Most residents of the island are tribal citizens, enrolled with the United Houma Nation or the Biloxi–Chitimacha–Choctaw Confederation of Muskogees. Families who have called the island home for generations are now faced with making the choice to remain and attempt to maintain a sense of sovereignty, even if that means living outside “risk-reduction” levees, surrounded by more water and less land, or to migrate to higher ground thirty miles inland, a world away from their bayou-side way of life.

I often wonder if I will be able to call St. Bernard home as I grow older or if I will have to relocate to higher ground north of Interstate 10, even though I know you can’t run from climate change. I recognize the long-term race against rising tides and disappearing land and find a strange solace in knowing that there have been many before me who have had to make the hard decision to pull up their roots and replant them elsewhere in search of a better life, like my grandparents did. But there is no place like home, especially when it happens to be the heart of the Mississippi River Delta, a biodiverse nexus of the planet. The great migration away from the coast has already begun, but the debate over staying in coastal communities or moving to higher ground continues.

Monique Verdin is an interdisciplinary storyteller who has intimately documented the complex interconnectedness of environment, culture, climate, and change in southeast Louisiana. She is director of the Land Memory Bank and Seed Exchange, a member of the United Houma Nation Tribal Council, and part of the Another Gulf Is Possible Collaborative core leadership circle of brown (indigenous, Latinx, and desi) women from Texas to Florida who work to envision just economies, vibrant communities, and sustainable ecologies.