What Might Have Happened at Manchac

New Orleans was nearly relocated to a site near Baton Rouge

Published: November 29, 2022

Last Updated: February 28, 2023

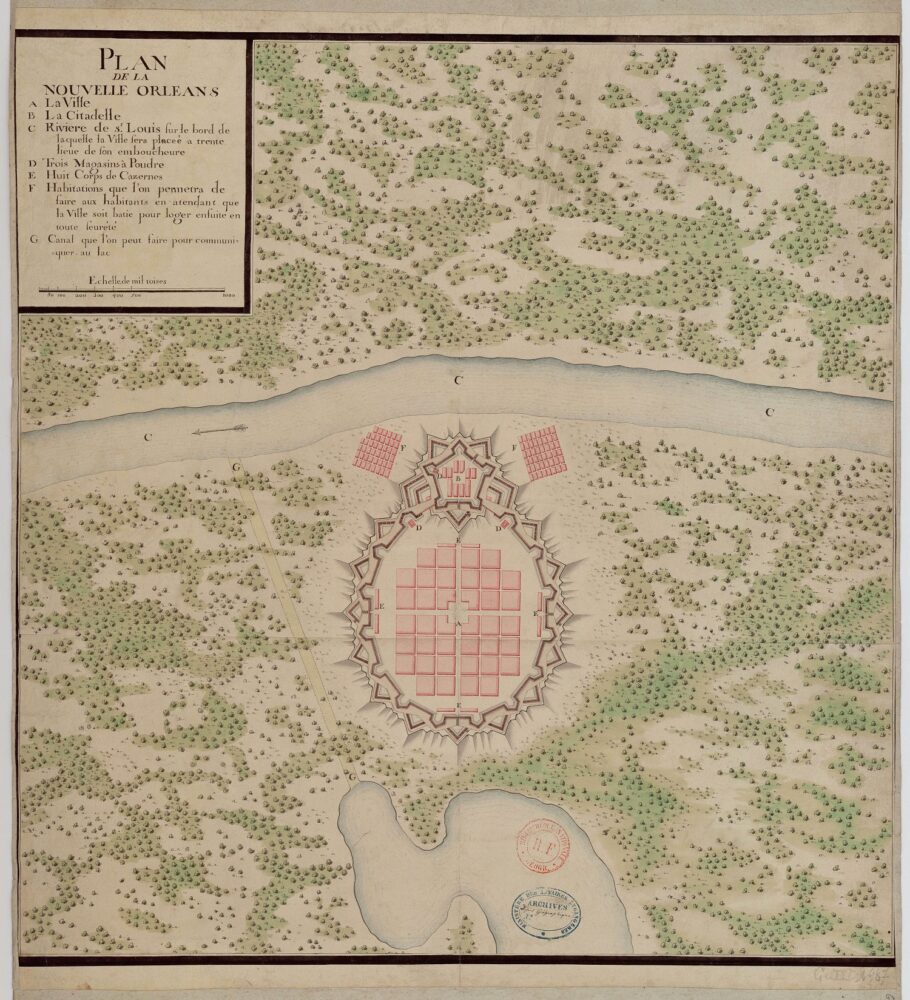

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des cartes et plans

Speculative vision for New Orleans attributed to Paul de Perrier, ca. 1718. Pen and ink with watercolor.

But in the 1700s, “Manchac” implied the bayou that flowed out of the Mississippi just south of present-day Baton Rouge, forming what are now the boundaries of East Baton Rouge, Iberville, and Ascension Parishes, after which it wended eastward as the Amite River, formerly the Iberville River. This distributary allowed navigators to sail or paddle small vessels from the Mississippi through the Manchac Swamp and Lake Maurepas, through Pass Manchac, across Lake Pontchartrain and out the Rigolets to reach the Gulf of Mexico. Alternately, they could sail in from the Gulf and take that multi-waterway route nearly to present-day Baton Rouge. It wasn’t easy, but it avoided some two hundred miles of strong currents and sandbars on the sinuous lower Mississippi, and so long as you were traveling light, it was worth it.

Bayou Manchac thus provided a rear entrance into lower Louisiana—which is exactly what imashaka meant in the Mugulasha tongue. Natives of various tribes rigorously used this shortcut to and from the sea whenever hydrological conditions permitted, and French colonizer Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, traveled the whole length of it during his explorations of 1699. Over the next two decades, the eyes of other colonial leaders were drawn to the headwaters of the Bayou Manchac route as a possible site for a settlement—not just any outpost, but the headquarters of the new company overseeing France’s Louisiana project.

On April 14, 1718, an unnamed official in Paris contemplated creating that new “counter office” for the Company of the West to fulfill its royal charter to develop Louisiana. The idea stemmed from a September 1717 company resolution “to establish, thirty leagues up the river, a burg which should be called La Nouvelle-Orléans, where landing would be possible from either the river or Lake Pontchartrain.” The company charged the siting of that burg to Iberville’s younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, who, drawing upon his nineteen years of regional experience, set out in February 1718 to scout a location. Sometime during March and April, Bienville and his men began work establishing New Orleans at what is now the French Quarter, ninety-five miles (roughly thirty leagues) up from the mouth of the Mississippi, near a portage that connected with Lake Pontchartrain—just as the 1717 resolution had stipulated.

But Bienville’s decision did not settle the matter. French colonials elsewhere, particularly in Mobile, Biloxi, and Natchez, wanted their outposts to become the company headquarters, and rebuked Bienville’s site as ill-suited and prone to flooding. Company officials in Paris felt compelled to intervene, despite that they only knew Louisiana vicariously. Add to this the hundred-day lag time to get a message across the Atlantic, and conditions were ripe for confusion and miscommunication over the biggest question of all: where to build New Orleans.

Which brings us to that April 14 letter, written precisely when—unbeknownst to its Parisian author—Bienville was already at work on his favored site for New Orleans. Titled in part “The Choice to Be Made for the Establishment of a Position in New Orleans, in a Way to Communicate with Mobile,” the letter issued “instruction[s] for Mr. Perrier, Chief Engineer of Louisiana,” and was intended to be sent with the recently appointed engineer as he departed France for his new duties. “What is most important for the Company,” the letter read, “is to have a perfect knowledge of the places where its vessels can be safe, and of the entrance to the Mississippy River [sic]. So, these are the first things, to which Mr. Perrier will give his full attention.” To the question of siting the headquarters: “We do not know where we will choose for the establishment of New Orleans,” the writer acknowledged, going on to say that ultimately this would be up to Perrier. But he also made clear that “the main attention to be paid” in selecting the site was that it be “put in the most convenient place for communication with Mobile, either by sea or by Lake Pontchartrain, least in danger of being flooded in overflows and, as far as possible, near the best land to cultivate.”

Then came the whopper: “These different considerations make us think … that the most suitable place is on the Manchac stream, [with] the city wall on the riverside and on the edge of the stream.”

French colonials elsewhere, particularly in Mobile, Biloxi, and Natchez, wanted their outposts to become the company headquarters, and rebuked Bienville’s site as ill-suited and prone to flooding.

The writer used the word ruisseau (stream or brook) to mean what Natives in Louisiana called a bayouk, or bayou. Clearly he meant Bayou Manchac, specifically where it branched off from the Mississippi River, a feature that appeared regularly on French maps of the era. “Examine it and see if the land is suitable,” the writer instructed Perrier. “Assuming it is, we would find New Orleans better placed here than elsewhere, for convenience communication with Mobile via the stream, which claims to be able to make it navigable at all times with little expense, and because it will also be very close to the entrance to the Red River.” That meant central and northern Louisiana, where the French considered themselves to have good relations with Native tribes, where they thought wheat could be grown, and where they expected to find good hunting and a more agreeable climate (la bonté de l’air—“the goodness of the air”).

There were some problems in putting New Orleans at Manchac, the writer acknowledged, namely “the distance from the sea, being at sixty-five leagues,” or nearly two hundred miles. But that’s where Manchac’s rear entrance would help: sailors could take the lakes if they wanted to avoid the river. “When we have determined … where we will place New Orleans, we believe that said Sieur Perrier will mark the enclosure of a fort that can later become a citadel[,] place the Company’s stores and the lodgings … of the major officers,” and lay out “the alignments of the streets, with the divisions of suitable land for each inhabitant within the city.”

Here we have New Orleans’s first urban planner—an anonymous company man, writing from Paris, sight unseen, of a locale near Baton Rouge, even while Bienville was actually creating New Orleans, at New Orleans! The letter was signed Fait à Paris, en l’Hostel de la Compagnie d’Occident (Made in Paris, in the Office of the Company of the West), dated le 14 avril 1718, and delivered to Perrier.

Perhaps based on these instructions, Perrier sketched out a Plan de la Nouvelle-Orléans depicting an entirely imaginary geography: a straight river surrounded by solid land, with a gem of a city that looked more like a sparkling pendant than a wilderness outpost. Perrier’s sketch startles and confuses people to this day, as it bears zero resemblance to anything in South Louisiana, much less modern New Orleans. Perhaps its otherworldly appearance was Perrier’s polite way of placating his know-it-all superior while he himself made his way to Louisiana and studied the geography firsthand.

Alas, Perrier died en route, apparently in Havana, the cause of his death lost to history. New Orleans’s first appointed engineer never made it to the city he was cajoled to relocate—by New Orleans’s first urban planner, contemplating a site near Baton Rouge from a desk in Paris.

Perrier’s untimely demise had epic consequences. For one, it bought Bienville precious time to continue toiling at the French Quarter site, making it ever harder to abandon the work done to date. For another, it led the company to replace Perrier with a new chief engineer, Pierre Le Blond de La Tour, along with an assistant, the highly capable Adrien de Pauger.

De La Tour went off to work on Biloxi, while Pauger was dispatched to Bienville’s New Orleans. Like Perrier, Pauger had also been instructed—perhaps by that same company official, in a letter dated November 8, 1719—“to examine the situation of this town [New Orleans] and if deemed necessary, relocating it to a more suitable place and less prone to flooding.”

But Pauger instead found Bienville’s site plenty suitable. He surveilled the natural levee, sketched out a street grid and fortifications, and proposed to move the whole urban footprint closer to the river, taking full advantage of limited topographic elevation. After studying the hydrology of the Mississippi, he surmised that navigational problems on the river could be overcome, making Bienville’s site ideal for a port city. The outspoken assistant engineer went so far as to rebuke the “stubbornness” and “arrogance” of company officials, who forced “ships from France to be stopped at Biloxi, rather than enter the Mississippi[,] keystone of the country’s establishment.”

Over the course of 1721, more and more momentum built for keeping New Orleans at Bienville’s site, while talk of Manchac disappeared from company directives. “The year 1721 had been generally favourable to New Orleans,” wrote the French historian Baron Marc de Villiers du Terrage many years later. “From a military post, a sales-counter, and a camping-ground for travelers, it had become, in November, a small town, and the number of its irreconcilable enemies began to decrease.” On December 23, 1721, company authorities officially transferred Louisiana’s capital from Biloxi to New Orleans.

Manchac would never get New Orleans; New Orleans would never end up near Baton Rouge; and no “fort,” “citadel,” “company stores and lodges,” or “alignments of streets” would ever come to what is now the Iberville–East Baton Rouge Parish line—a line still demarcated by wending Bayou Manchac, its adjacent fields inviting us to ponder: What might have happened at Manchac?

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached at richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.