Why Is Grand Isle in Jefferson Parish?

Notes on parish topography

Published: May 31, 2023

Last Updated: August 31, 2023

Map and Analysis by Richard Campanella

First, some history. Following the Louisiana Purchase, American administrators brought to the new territory their apparatus of governance, much of which entailed the drawing of lines on maps. In 1805 they designated twelve “counties” throughout Louisiana, to serve as electoral and taxation jurisdictions. Among them was Orleans County, which encompassed the southeastern corner of our present-day state—nearly all of today’s Jefferson, Orleans, St. Bernard, and Plaquemines Parishes, including Grand Isle to the south and the Chandeleur Islands far to the east.

To Louisiana Creoles, “counties” were unfamiliar and unwelcome. Being overwhelmingly Catholic, these residents had long spatialized themselves by ecclesiastical parishes—that is, by where they attended Mass and received the sacraments—so much so that American officials explicitly invoked the names of parish churches to inform which lands now pertained to which new counties. It should be noted that most ecclesiastical parishes were not precisely mapped with hard boundaries; folks simply attended their nearest church or chapel, and over the years, those catchment areas became ecclesiastical parishes.

Needing also to create a system of courts, American officials in 1807 made a concession to Creoles and adopted their term of “parishes” in the naming of new judicial jurisdictions. Unlike the ad-hoc ecclesiastical parishes, however, these nineteen new judicial parishes would need legal boundaries, and much like those ecclesiastical catchment areas, authorities looked to church-attendance patterns to inform how the new units would be drawn. Orleans County, having the largest population among the counties drawn for electoral and taxation purposes, split into three new judicial parishes: Plaquemines Parish, St. Bernard Parish, and Orleans Parish, the last including present-day Jefferson as well as Orleans.

… some lands were in Orleans County, in Orleans Parish, and in the City of New Orleans, while others were in the first only, or the first and second but not the third.

Both counties and parishes would coexist for a generation to come, each for different purposes and with mostly (but not entirely) differing boundaries, some rather vague. Additionally, toponyms could have multiple meanings and spaces. “Orleans,” for example, meant a county as well as a parish; some lands were in Orleans County, in Orleans Parish, and in the City of New Orleans, while others were in the first only, or the first and second but not the third. There were also wards and senatorial districts, each with their own borders. It was confusing, to say the least.

In the decades ahead, denizens of rural Orleans Parish, namely French-speaking Creole planters, felt their interests were being ignored by representatives of the City of New Orleans, where English-speaking American newcomers were on the rise. In 1825 the planters succeeded in getting the state legislature to create a new parish out of Orleans Parish’s western flank, named to honor former President Thomas Jefferson and based on the borders of the Third Senatorial District, which extended all the way south across the Barataria Basin to Grand Isle. Why? Because that earlier entity of Orleans County had stretched seaward in every direction—eastward, southeastward, and southward. Thus, Grand Isle ended up in Jefferson Parish, and remains there today.

Now, some geography. Jefferson Parish, like all areas along the lowermost Mississippi, formed as the river and its distributaries overtopped their channels and deposited sediment to form ridges (natural levees) across swamps and marshes petering out to brackish bays (lakes). Fifteen parishes throughout the southeastern corner of our state arose under these processes, all within the last seven thousand years, and their soils are entirely alluvial, without any older, firmer uplands. Indigenous people managed to thrive on both the natural levees and coastal marshes, but Europeans, seeking to establish a permanent colony with slavery-based commodity plantations, saw divergent value in these delta landscapes, with the higher natural levees being of far greater utility than the soggy lowlands. So when the time came to demarcate these environs administratively, it behooved the emerging political economy to give each jurisdiction a full slice of the topographical profile.

Viewed from that perspective, it makes sense that Grand Isle (as well as the lower Barataria Basin) would be in Jefferson Parish—just as it makes sense that Orleans Parish would span from the river across the eastern marshes to remote Rigolets Pass; that St. Bernard would extend out to the distant Chandeleur Islands; and that Plaquemines Parish would sweep outwardly from the natural levees to the lateral saline marshes. Indeed, every one of Louisiana’s deltaic parishes exhibits these disparate topographies. Some straddle a natural levee or levees; others flail out from one main ridge; but all have the full high-to-low topographic profile. Any other delineation method would have made some parishes too valuable (all natural levee), and others too “worthless” (all wetlands).

… Europeans, seeking to establish a permanent colony with slavery-based commodity plantations, saw divergent value in these delta landscapes, with the higher natural levees being of far greater utility than the soggy lowlands.

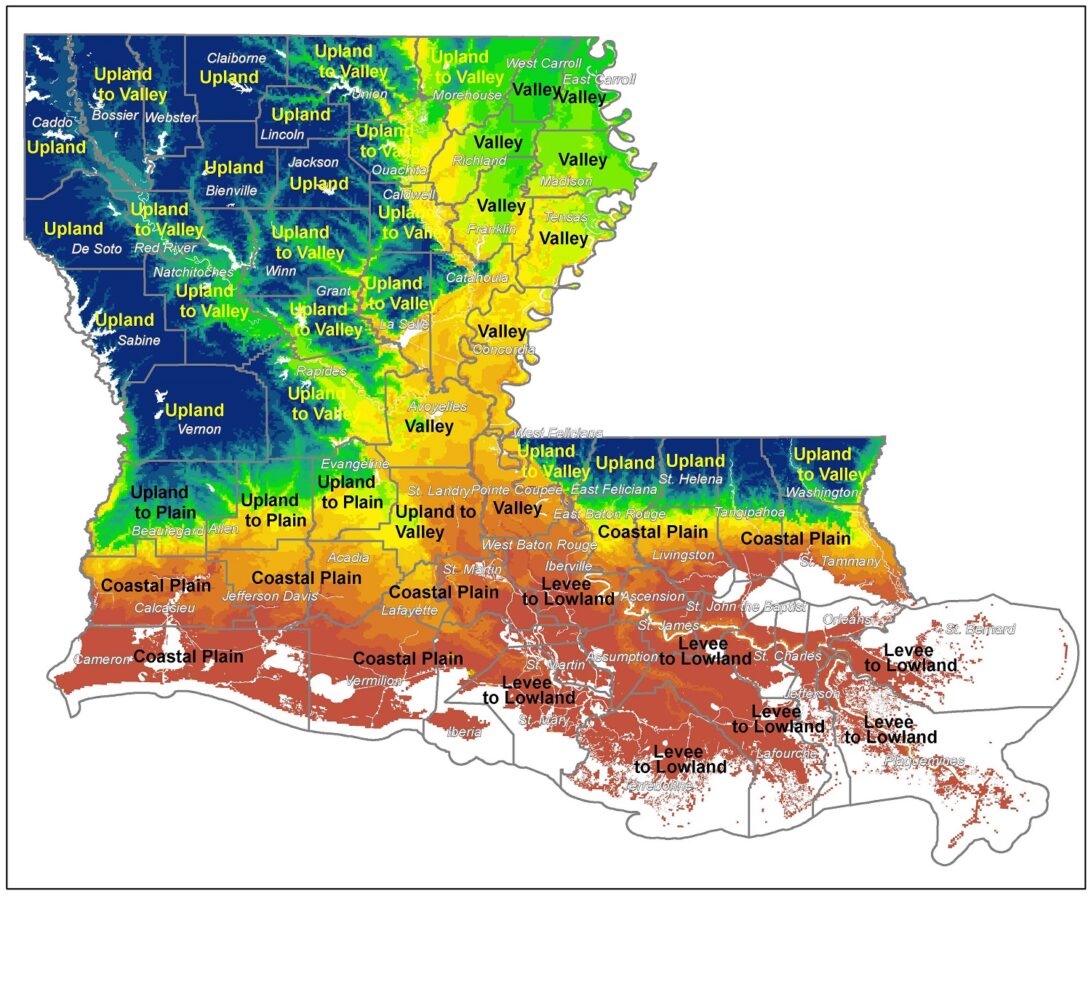

Applying these same criteria to other Louisiana parishes, we start to see other topographical tendencies. The Chenier Plain parishes of Vermilion and Cameron, which formed as sediments deposited by the Mississippi River were swept westwardly by longshore currents, each slope downwardly to Gulf waters from the older, higher prairie terraces to their north, again traversing the full topographic profile. The accompanying map labels these parishes as being “Coastal Plain” in their prevailing topography, a trait they share with certain Florida Parishes two hundred miles to the east, which also slope downwardly, from the piney woods of the Pleistocene Terrace to the swamps and marshes of the lakes (bays) of Maurepas, Pontchartrain, and Borgne.

Now let’s look to northwestern Louisiana, whose undulating terrain is millions of years old and includes the state’s highest point, 535-foot-high Driskill Mountain in Bienville Parish. Those parishes dominated by these gentle and occasionally rocky hills are labeled Uplands in the accompanying map, while those that mostly slope downwardly are labelled as Upland-to-Valley or Upland-to-Plain, depending on adjacent features. Once again, certain Florida Parishes may be categorized in the same way as some parishes two hundred miles to the northwest. For example, West Feliciana Parish spans from the rugged loess bluffs down to the silty Mississippi Valley, while Washington Parish encompasses terraces as high as three hundred feet above sea level down to the valley of the Pearl River as it approaches the Gulf of Mexico.

We also have a number of parishes (nine or so, depending on criteria) that have mostly valley morphologies, meaning a broad flat floodplain with topographic “walls” situated farther away. In the vernacular, these northern parishes are often referred to as the Louisiana Delta or the Upper Delta, but geologically speaking, it’s more accurate to think of these bottomlands as comprising the lower Mississippi Valley. To their west are uplands that are thoroughly interspersed with secondary valleys, such as those of the Ouachita and Red Rivers; they are labelled as Upland-to-Valley parishes on the accompanying map, and once again, they transect their respective region’s full topographical profile.

Physical geography has informed human history in the delineation of every one of our sixty-four parishes. But make no mistake: people have agency, not geography, and the county and parish lines people have drawn and redrawn reflect the notions of empowered parties as to how geography might be utilized to advance the political spaces they were creating. One may conclude that geographical rationality explains why Grand Isle ended up in Jefferson Parish, but it is only through the lens of a specific economic aspiration that this particular notion of “rationality” comes into focus.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Draining New Orleans, The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached at richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella.