Los Adaes

The history of the fort, mission, and settlement of Los Adaes reflects both intercolonial rivalry and cooperation among the Spanish, French, and Native Americans who lived along the border of New Spain and French Louisiana.

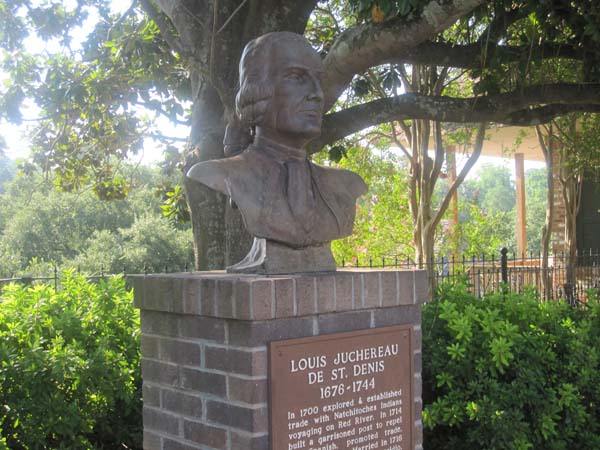

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Louis Juchereau de St. Denis. Hathorn, Billy (photographer)

In 1721 the Spanish built a presidio, or fort, and mission in an area inhabited by the Adaes Indians near present-day Robeline, in northwest Louisiana, that served as the official capital of the Spanish province of Texas from 1729 to 1770. The presidio was named Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza de los Adaes, and the mission—located within a quarter mile—was named San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes. The fort, mission, and settlement that evolved came to be called simply Los Adaes. Its history reflects both intercolonial rivalry and cooperation among the Spanish, French, and Native Americans who lived along the border of New Spain and French Louisiana.

An earlier Spanish mission for the Adaes had been built roughly one and a half miles to the southwest in 1717. It was constructed in response to the French trading post among the Natchitoches Indians established by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis in 1713 at the present-day city of Natchitoches. St. Denis had traveled to Presidio San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande in search of Father Miguel Hidalgo, who had written a letter to the Louisiana governor Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, offering introductions to Spanish traders in exchange for support of the reestablishment of missions in the area of eastern Texas. These two missions, which had been established in eastern Texas in 1690, had been abandoned at the insistence of the local Hasinai Indians after complaints that Spanish soldiers made inappropriate advances to the tribe’s women and that the Spaniards’ cattle disrupted the Hasinai’s farms.

It is unknown whether St. Denis ever found Father Hidalgo, but the response to St. Denis’s visit to Presidio San Juan Bautista was a Spanish expedition in 1716–17 that set up presidios and missions across Texas to counter the French threat at Natchitoches. St. Denis, who eventually married the step-granddaughter of Diego Ramón, the commandant of Presidio San Juan Bautista, was asked to guide this expedition, as it was led by Ramón’s son, Domingo. Established as part of the Ramón expedition, the 1717 mission was initially named San Miguel de Linares de los Adaes; in 1718 the name was changed to San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes. The French from the Natchitoches post attacked it in 1719 as part of the War of the Quadruple Alliance between France and Spain, and the Spanish withdrew from the eastern area of Texas.

Crossroads of Colonial Empires

The attack prompted José de Azlor y Virto de Vera, the Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo, to lead and fund an expedition to reestablish the Spanish foothold in eastern Texas. In 1721 the Aguayo expedition reestablished Mission San Miguel in a more defensible position and built the presidio close to it. Thirty-one of the one hundred soldiers associated with Presidio Nuestra Señora del Pilar de los Adaes were married: Aguayo was well aware of the mistakes of the earlier missions in eastern Texas, and he wanted to make sure that the soldiers assigned to the missions were family men. Aguayo was made governor of the provinces of Coahuila and Texas in 1719, when he promised to finance the expedition. When he resigned as governor in 1722, he left the Spanish province of Texas better fortified, with four presidios and ten missions. Before his tenure, the vast territory had had only one presidio and two missions.

After the Aguayo expedition, the Spanish in Texas braced for an offensive by the French, but this attack never came. Instead, the French lieutenant responsible for the attack in 1719 (now referred to as the Chicken War because the French took the Spaniards’ chickens as part of the encounter) was reprimanded, and items taken from Mission San Miguel were returned. An inspection of the presidios of Texas in 1727 by Pedro de Rivera revealed a peaceful situation on the Spanish/French frontier. Rivera entered Presidio de los Tejas (Presidio Dolores) on the Neches River in eastern Texas and found no one on guard duty. The soldiers explained that they got along so well with the local Native Americans that they did not post guards. Rivera also observed no Indians living at any of the six missions of eastern provincial Texas, including Mission San Miguel.

Rivera recommended closing Presidio de los Tejas and reducing the number of soldiers stationed at Los Adaes from one hundred to sixty. There were only twenty-five soldiers at the nearby French Fort St. Jean Baptiste aux Natchitoches. The lack of Native Americans living at the missions in eastern Texas resulted in consolidating three of the six missions to San Antonio. Therefore, after 1730 only three missions existed—Mission Guadalupe (among the Nacogdoches Indians at present-day Nacogdoches, Texas), Mission Dolores (at present-day San Augustine, Texas), and Mission San Miguel—and one presidio, Los Adaes, remained in the easternmost region of Texas.

Cross-cultural Cooperation and Trade

The period after 1721 was generally a time of cooperation and accommodation between the French and Spanish in the area. The priests from Los Adaes would conduct Mass and tend to the spiritual needs of the populace at Fort St. Jean Baptiste when the French post did not have a priest. When the Natchez Indians attacked Fort St. Jean Baptiste in 1730, Los Adaes soldiers and Hasinai warriors went to help the French. Although the people of Los Adaes cultivated crops and raised cattle, the settlement was not self-sufficient. Trade with the French for food was allowed, but the Spanish forbade trading with them for merchandise. The Spanish were prohibited from trading firearms or alcohol to Native Americans; however, the French had nonrestrictive trade policies toward both the Spanish and the Native Americans. In general, the French needed horses and cattle, and the Spanish needed foodstuffs and French cloth. In exchange for metal implements, cloth, and glass beads, the Native Americans provided foodstuffs to both the French and the Spanish.

Archaeological investigations at Los Adaes indicate a great deal of Spanish interaction with both the French and the Native Americans. French pottery fragments are just as numerous as those made in Spanish Mexico, but fragments of Native American pottery are most abundant, numbering more than thirty thousand. Some of the Native American pottery at Los Adaes was tableware in the shape of European vessel forms, and other items included cookware, but it is likely that much of the pottery functioned as food transport and storage containers. Fragments of French firearms and knives have been recovered from Los Adaes; most of the gunflints are French in origin. When it comes to horse gear, however, only fragments of Spanish-style spurs, bits, and saddle-apron jinglers have been found at Los Adaes.

Intermarriage certainly took place among the Spanish, Africans, and Native Americans in New Spain, as a 1731 roster of the Los Adaes soldiers attests. It gives the casta (ethnicity) of each soldier: almost half of them are described as Espanol, or Spanish, while the rest are Mestizo (Spanish and Native Americans), Mulato (Spanish and African), Lobo (Native Americans and Mulato), and Coyote (Native Americans and Mestizo). In the early decades of the 1700s, roughly twenty-five percent of the population of New Spain was of mixed heritage, so it seems that soldiers of mixed heritage were more likely to serve on a frontier post like Los Adaes. The extent of intermarriage among the Spanish, French, and Native Americans at Los Adaes, however, is less clear.

The governors at Los Adaes generally served terms of two to four years until 1751, when there were two governors who served terms of eight and seven years, to 1766. Historical documents reveal that while many of the governors boasted few or no negative incidents, abuses of power did abound. The governors paid the soldiers in goods, and every year the soldiers would sign a document giving a representative of the governor power of attorney to go to Mexico City, collect the soldiers’ pay, buy goods and supplies, and then return to Los Adaes. The governor could therefore make a profit on the goods, since he determined their value once they were brought to Los Adaes. For example, Governor Francisco García Larios (1744–1748) was accused of buying forty cakes of soap for one peso in Saltillo and charging one peso for ten cakes of soap at Los Adaes. Governor Sandoval (1734–1736) was charged with not paying the soldiers for his entire term. Governor Winthuysen (1741–1743) was one of the more progressive governors, as he renovated the stockade and built five new barracks. Winthuysen’s report of 1744 suggested reducing the troop strength at Los Adaes, arguing that even six hundred Spanish soldiers at Los Adaes would not be enough if the French were to attack because the French could rely on large numbers of Native American allies.

Closing the Presidio and Mission

The end of the French and Indian War was a pivotal event for Los Adaes. On November 3, 1762, when it was clear that they would lose the war, the French ceded New Orleans and all holdings west of the Mississippi River to their Spanish allies as part of the Treaty of Fontainebleau so that the British would not get complete control of the Mississippi River. Fort St. Jean Baptiste therefore became Spanish, and an inspection of presidios and missions on the northern frontier was undertaken to determine which facilities would be necessary now that the French threat was gone. The military inspection at Los Adaes in 1767 found a presidio that was not exactly living up to the highest military standards: only two operable firearms were found in the armory, and the soldiers were lacking the required number of horses. Apparently, some of the Spanish soldiers were trading their horses for bottles of French wine. The inspection of the eastern Texas missions in 1768 found that the priests were attending to the needs of the faithful, but there were no Native Americans living at the missions. The recommendation of both military and religious inspections was to close the three missions and presidio of eastern Texas. The capital was moved to San Antonio in 1770, and Los Adaes was abandoned in 1773.

Most of the Adaeseños (as people from Los Adaes came to be known) migrated to San Antonio, Texas, although some went east to Louisiana and others went to live with the Native Americans. Almost immediately, some of the Adaeseños in San Antonio petitioned to return to eastern Texas. In 1774 the group was allowed to settle on the Trinity River, where their community was called Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Bucareli. Attacks by Comanche Indians and epidemics caused the abandonment of Bucareli, and the Adaeseños moved to the site of the former mission for the Nacogdoches in 1779.

Today, Adaeseño descendants are found in both Texas and Louisiana. The site of Los Adaes is administered by the state of Louisiana as the Los Adaes State Historic Site. It has proven to be one of the most important archaeological sites in the United States for the study of colonial Spanish culture and is open to the public by appointment.