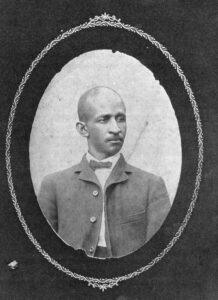

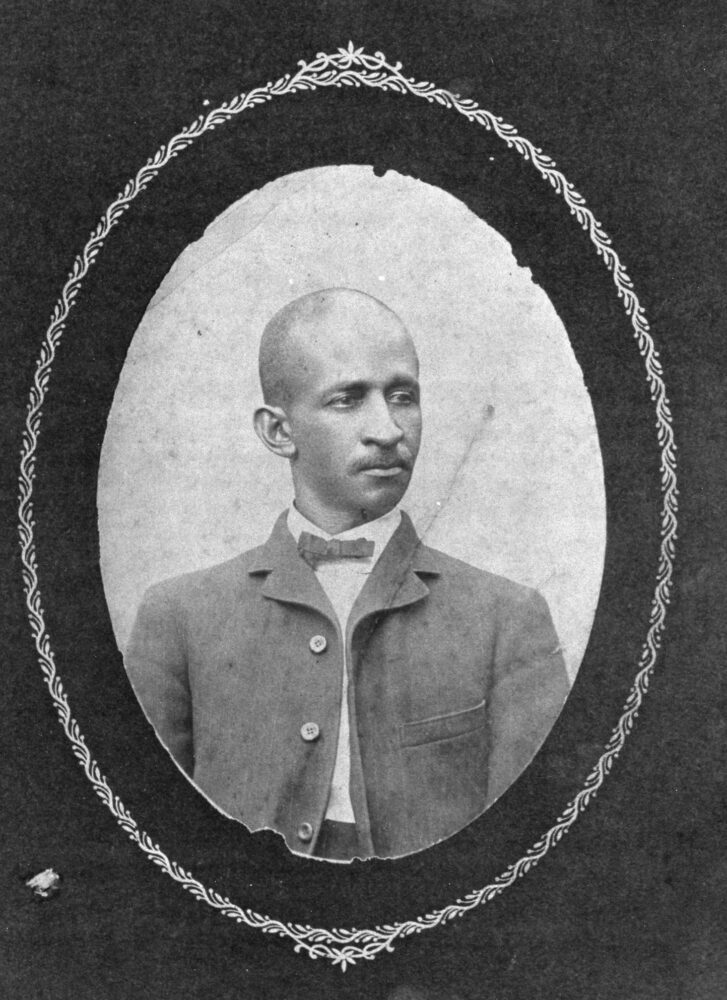

C. C. Antoine

Caesar Carpentier “C. C.” Antoine served as lieutenant governor of Louisiana from 1873 to 1877, one of only three individuals of African descent to hold the office during Reconstruction.

Northwest Louisiana Archives at LSU Shreveport

Caesar Carpentier “C. C.” Antoine, ca. 1873.

Caesar Carpentier “C. C.” Antoine, born in 1836, served as lieutenant governor of Louisiana from 1873 to 1877. He was the third of three Black Republicans who held the office during Reconstruction, following in succession behind Oscar Dunn and P. B. S. Pinchback. Never enslaved, Antoine was born in New Orleans in 1836 and raised in a family of free people of color. He was elected in 1872 on the ticket headed by gubernatorial candidate William Pitt Kellogg during a time when Confederate veterans were disenfranchised, and the state was under federal control following the South’s loss in the Civil War. During this twelve-year period of political tumult and social upheaval, individuals of African descent briefly held power in the highest offices in the state before the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction and ushered in the Jim Crow era.

Early Life and Political Career

Antoine’s father was a mixed-race veteran of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, and his mother was a native of the West Indies and the daughter of an African chief who had been sold into slavery. Privately educated in New Orleans in both French and English, Antoine eventually made a career as a barber. In 1862 after the Union capture of New Orleans, he raised a company of Black soldiers composed of both enslaved and free men of color, who joined the Northern forces as Company I, 7th Louisiana Militia. Antoine, who put the brigade together in a mere forty-eight hours, was elected captain and led his troops in minor battles.

At the war’s end Antoine immediately became involved in the political life of New Orleans, serving first as chairman of the Resolutions Committee for the Lincoln Memorial program in 1865. Ostensibly a memorial service for the slain president, the program was, more importantly, a political rally widely attended by people of African descent and held in Congo Square in support of Louisiana’s restoration to the Union. That same year Antoine became associate editor of the Black Republican, a short-lived newspaper aimed at the Black and mixed-race population of New Orleans. The name was chosen for irony and shock value, as the term “black Republican” was at the time widely used in reference to Radical Republicanism, a political movement that sought to eradicate the institution of slavery.

In 1866 Antoine left the chaotic environment of occupied New Orleans and relocated to Shreveport, where he established himself in the grocery business. However, the political turmoil and societal upheaval of Reconstruction followed Antoine to the burgeoning North Louisiana city where it affected him profoundly. His son, Joseph Antoine, was killed in a race riot preceding the national elections of 1868. In that same year Antoine declared himself a candidate for state office and was elected a senator. The state legislature was 33 percent Black in the House of Representatives and 20 percent in the Senate at a time when southern white supremacists were systematically excluded from government. In 1872 Antoine advanced to the lieutenant governor’s office by popular vote, serving first under Pinchback, Louisiana’s only governor of African descent, who was sworn into that position for thirty-five days between the impeachment of Governor Henry Clay Warmouth and the inauguration of Kellogg. On September 14, 1874, a mob of outraged white citizens led a coup d’état in New Orleans, commonly known as the Battle of Liberty Place, to oust Kellogg and his fellow Republicans. However, federal troops under orders from President Ulysses S. Grant promptly restored order, and the Reconstruction government remained in power.

Some historians have posited that many of Louisiana’s Black politicians elected during Reconstruction were placed in office by Radical Republicans to humiliate the South’s white population more than to help its newly emancipated Black population. Still, such was not the case with Antoine. Among both Black and white Republicans, there was corruption, but Antoine was considered trustworthy as well as a strong civic advocate for Shreveport. His efforts to clean up questionable practices in state government made enemies among his colleagues of both races. His opposition to the notoriously corrupt Louisiana Lottery Company was a sore spot for many government officials known to be skimming money from the lottery’s coffers.

In 1868 Antoine was a member of the constitutional convention that drafted a new state constitution, and in 1869, while a state senator, he sponsored a bill to establish the first charity hospital in Shreveport. In 1871 he authored a bill to incorporate Shreveport as a city (it had been incorporated as a town in 1839, but not until the passage of Antoine’s bill did Shreveport achieve legal status as a city). Many of Shreveport’s government agencies, including the modern police department, came into being as a result of legislation authored by Antoine. Through his efforts, Shreveport’s first city hall was built in 1872 at the northwest corner of Milam and Louisiana Streets. Before its construction, the mayor had to provide his own office space while other city offices were housed in rented quarters around town.

In 1876 Antoine ran for re-election to the lieutenant governor’s office on the Republican ticket alongside gubernatorial candidate Stephen B. Packard. Although the returning board declared Packard the winner, Democratic candidate Francis T. Nicholls, a Confederate veteran and double amputee, defiantly dismissed the official results of the election. Nicholls seized the governor’s office by force, installing a de facto state government that effectively pushed the Republican regime out of office. With a force of 3,000 troops, Nicholls seized the Cabildo in New Orleans, headquarters of the Republicans, who immediately surrendered. Nicholls then proceeded to dissolve the State Supreme Court and appoint a new judiciary, thus re-establishing “home rule” for the first time since the outbreak of the Civil War. Federal troops left Louisiana in 1877 in a national compromise that allowed for the certified election of President Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the end of Reconstruction. It would be nearly ninety years before Black Louisianans again enjoyed full participation in the government and politics of their state.

Post-Reconstruction

With the end of the postwar experiment of racial equality and the restoration of white supremacy in Louisiana, Antoine returned to living part time in Shreveport where he had already attained a comfortable financial position. In addition to managing a thriving grocery business, Antoine was partners with Pinchback in a New Orleans cotton factorage business, and for many years Antoine was the owner of a cotton plantation in Caddo Parish. He also made money speculating in real estate in the Allendale and West End neighborhoods of Shreveport and was president of the Cosmopolitan Life Insurance Company of Louisiana.

In 1887 Antoine co-founded and became vice president of the Comité des Citoyens, an organization in New Orleans founded to fight legal battles against racial discrimination. The Comité was the successor to an organization known as the Unification Movement, of which Antoine had been a co-founder in 1873. The Unification Movement, with its initial membership consisting of fifty white and fifty Black New Orleanians, was one of the first civil rights organizations in Louisiana and had as its goal complete racial equality for all residents of the state. When the Comité des Citoyens came into being, it was with the same goals and much of the same leadership as the Unification Movement, though with a more proactive and less passive posture. In 1890 the Comité challenged segregation by engaging a light-skinned New Orleanian named Homer Plessy to test the constitutionality of Jim Crow legislation when he boarded a whites-only railcar in New Orleans. Plessy’s arrest and the subsequent series of trials that led to the Supreme Court resulted in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson decision upholding the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Though the verdict of the justices maintained the constitutionality of separate facilities for whites and people of color, the notion that those facilities be “equal” was, at the time, viewed by many as progressive. For Antoine and the Comité, however, the outcome of the case was seen as a defeat.

In 1892 Antoine was prosecuted in Orleans Parish Criminal Court by District Attorney Charles A. Butler for failing to inform a property buyer about a lien. Typically such an infraction would not lead to an arrest and a high-profile trial by the district attorney himself. However, Antoine’s prominence in the Comité des Citoyens and the Plessy case—then being heard in Orleans District Court where Butler’s assistant, Lionel Adams, was prosecuting Plessy—made him a target. Thus, a minor real estate oversight that normally would never have been considered a criminal matter became overnight an excuse to bestow a criminal record upon him.

Death and Legacy

On September 10, 1921, at the age of 85, Antoine died at his residence at 1941 Perrin Street in Shreveport’s Allendale section. Although an influential member of St. Paul’s Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, Antoine is buried in the New Bethlehem Baptist Church Cemetery. He is commemorated by C. C. Antoine Park on Milam Street in the Allendale area. Dedicated on May 26, 1984, a granite marker stands at the park’s center bearing a portrait of Antoine and a list of his political accomplishments. His Perrin Street home, Antoine’s sole surviving Louisiana residence, was entered into the National Register of Historic Places on August 20, 1999, but was lost to a fire in May 2022. Shreveport also hosts a C. C. Antoine Black History Month Celebration that began in 2008.