New Orleans Tribune

America’s first Black daily newspaper, the New Orleans Tribune served as an organizing tool for Black activists as they campaigned for rights for men of African descent with an emphasis on building solidarity with the formerly enslaved.

Roudanez History & Legacy

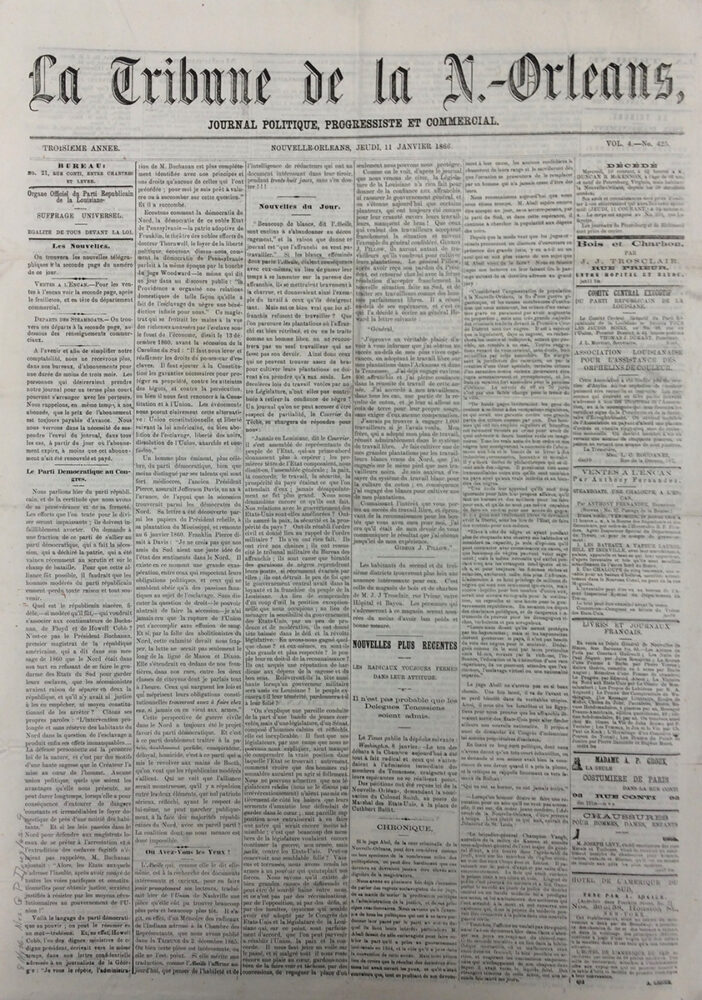

The January 1, 1866, edition of the New Orleans Tribune, America’s first Black daily newspaper.

America’s first Black daily newspaper, the New Orleans Tribune (1864–1869) was a radical, internationally respected journal that campaigned for full citizenship rights for all men of African descent. The newspaper pursued many of the same reforms as its predecessor, L’Union, but with a much greater emphasis on building solidarity with the formerly enslaved. A powerful Black freedom movement coalesced around the Tribune, resulting in many progressive changes in Louisiana.

The Tribune debuted on July 21, 1864, as a tri-weekly publication, selling for five cents or for an annual subscription price of six dollars. The journal became a daily on October 4, 1864. Published in French and English, it was read in Louisiana’s francophone community of free people of color and by a much wider English-speaking audience. In late 1866 the Tribune subscribed to the wire services of the Associated Press, allowing for rapid transmission of news articles. (This new technology conveyed news dispatches via thousands of miles of telegraph wire.) The four-page newspaper gradually enlarged to seven columns. Circulation grew, and after the Civil War more than three thousand issues were printed daily.

The Tribune had a large reach. It was distributed in the US Congress and among Northern abolitionist groups. “I read it with very great pleasure,” commented Frederick Douglass. “I am proud that a press so true and wise is devoted to the interests of liberty and equality.” Many Northern newspapers reprinted news from the Tribune, expanding its influence. The journal included the writing of Victor Hugo, Giuseppe Garibaldi, and others, and issues circulated in Europe’s intellectual community. The Tribune kept the world informed about the treatment of Black Louisianans and became a testament to their struggles during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras.

Several prominent New Orleanians worked at the Tribune including its founder, Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez and publisher Jean Baptiste Roudanez. The paper was edited by Paul Trévigne and later by Jean Charles Houzeau. Writers and staff included J. Clovis Lazier, Moses Avery, Armand Lanusse, Joanni Questy, Camille Naudin, Henry Rey, Charles Testut, Adolphe Testut, Adolphe Duhart, Michel Séligny, Louis Fouché, and Édouard Tinchant. Most articles did not include bylines, making it difficult to determine the full roster of contributors.

The Tribune was a decidedly militant publication that served as an organizing tool for Black activists. “It is not by remaining isolated that the oppressed can gain redress,” stated an early editorial. “It is only by coming out in a phalanx, by marching in a strong column, that we shall obtain our due. Let the people know, all over the land, who we are and many we are. Let us organize in one body and march through the streets and proclaim, ‘Here are the freedmen who claim their rights.’ ” The newspaper vigorously agitated for equality and justice, often championing mutual aid, mass meetings, and public demonstrations.

In addition to its promotion of civil rights and fiery condemnation of white supremacy, the Tribune’s French section featured philosophical and historical treatises, serialized fiction, and some of the first Black poetry, much of it political in nature, to be published in the United States.

The Tribune advanced issues of central importance to all Black people. “We demand,” it proclaimed, “the right to come and go; the right to vote; the right to public instruction; the right to hold public office; the right to be judged, treated, and governed according to the common law.” The newspaper’s agenda included land for the newly emancipated, streetcar desegregation, the right of entrance to public facilities, “recourse to personal defense,” proportional representation in the state legislature, the creation of integrated public schools, fair treatment for Black soldiers, abolition of Black code laws, and much more. As the voice of the Black community, the Tribune published news that would have otherwise gone unreported, including many incidents of white terrorism throughout Louisiana.

The newspaper emphasized Black solidarity. “We are the organ of the whole colored population. The Tribune has always defended the interest of every colored man, without regard as to whether he was free before or since the war.” The topic of limited as opposed to universal Black male enfranchisement was the subject of intense local and national debate. The Tribune consistently branded offers of partial suffrage as a divide and conquer tactic, insisting that all Black men had a right to vote and fully participate in civil society.

In 1865 the Tribune served as the official organ of the local branch of the National Equal Rights League and, later, the Friends of Universal Suffrage. That same year, the newspaper promoted statewide “mock” elections in which more than nineteen thousand unofficial ballots were cast. The Tribune later became the official organ of the Republican Party of Louisiana. In 1867 the journal identified with the “Radical Republicans” and coordinated the first official registration of more than eighty thousand Black voters who turned out in large numbers to elect delegates to an upcoming state constitutional convention. Those representatives, half of whom were Black, would later frame a constitution that mandated strong civil rights provisions, including many of the citizenship rights the Tribune had crusaded for.

In early 1868 the Tribune endorsed Thomas Durant, a white radical Unionist, for governor. When Durant declined the nomination, the journal advanced the candidacy of former Black military officer Francis Dumas. In a very close vote, the nomination went to Henry Clay Warmoth, a white lawyer from Illinois. Furious at the result, Louis Charles Roudanez refused to support the Republican ticket, and the newspaper slated their own candidates. The repudiation of the Republican ticket proved costly. Censured by the Republican Party and delisted as an official organ of the US government, the journal lost organizational and financial support. In April 1868 the Tribune ceased regular publication. It appeared sporadically through 1869 before permanently closing.

The Tribune’s legacy endured. The next generation of Louisiana activists would coalesce around another Black newspaper, the Crusader. That journal included the writing of former Tribune editor Paul Trévigne in the fight against racial oppression.