Jean Baptiste Roudanez

A radical civil rights advocate during the Civil War and Reconstruction, Jean Baptiste Roudanez helped found two historic Black newspapers.

Roudanez History & Legacy

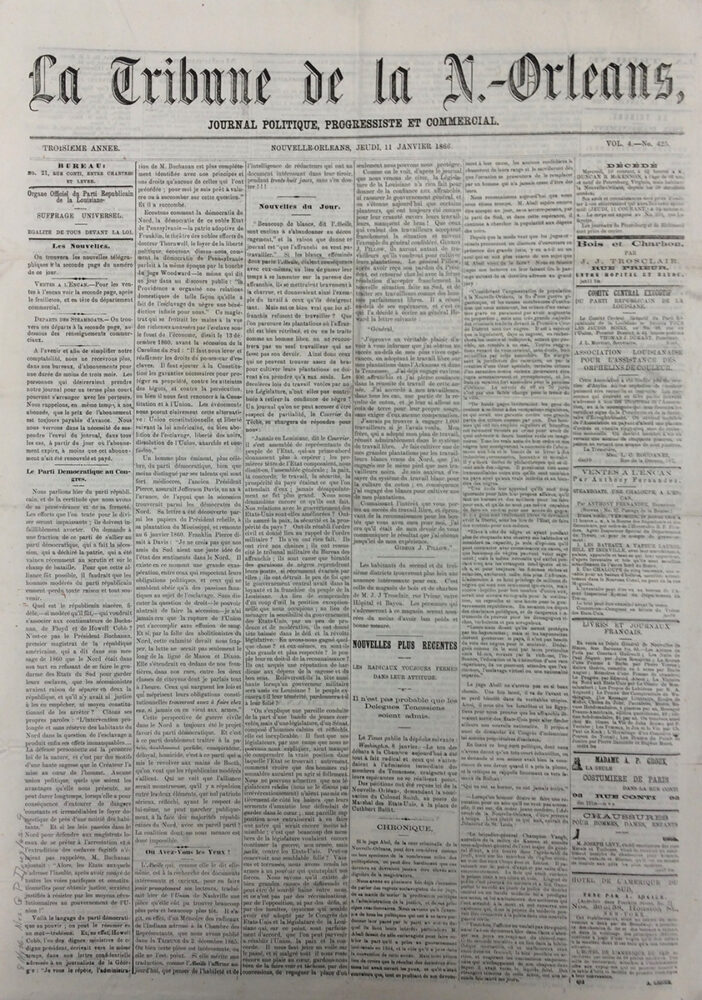

Roudanez helped found the New Orleans Tribune. The January 11, 1866, edition is picture here.

Jean Baptiste Roudanez was a radical civil rights activist during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. Nicknamed Eugene, he worked for many years as a kettle setter on sugar plantations in Saint James Parish. Soon after Union forces occupied New Orleans in 1862, Roudanez helped found L’Union (1862–1864), the South’s first Black newspaper. Roudanez later served as the publisher the New Orleans Tribune (1864–1869), America’s first Black daily newspaper. Both papers were financed by Roudanez’s brother, Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez.

Roudanez was born in 1815 in New Orleans to Aimée Potens, a free woman of color, and Louis Roudanez, a white refugee from the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Details of Roudanez’s early plantation life remain difficult to confirm. It is likely he spent his early years on the Bringier Plantations where his mother worked as a midwife. By 1854 Roudanez was in New Orleans advertising valuable services as a kettle-setter, offering a means to achieve a coarsely granulated product to “all Sugar Planters that may require their kettles put upon a strong and economical plan of fuel.”

The 1864 Freedman’s Inquiry Commission described Roudanez, then forty-nine years old, as “a free mulatto creole of New Orleans, a man of great intelligence and probity, who had been employed as an engineer and mechanic upon many of the sugar plantations in the region of the country under consideration. No man could have had a more thorough acquaintance with plantation life than he, and no man in the city of his residence bears a higher reputation for truth and sobriety.” According to Roudanez’s Commission testimony, “Slaves worked around the clock during the short autumn harvest season to keep the massive sugar kettles going. They labored in the dark and often sustained third-degree burns as they ladled the hot cane juice from kettle to kettle. Infections set in and often proved fatal. Slaves chained together feeding cane into the crushing mill often had limbs amputated on the spot lest they both be drawn into the crushing wheels. Punishment by whip was common.” Roudanez further testified, “Upon some plantations the women were worked as hard as the men and were kept at labor in every stage of pregnancy, even up to the moment of delivery. The overseers had the run of all the field women, and if one of them refused, an occasion was soon found for subjecting her to a severe punishment. The practice of indiscriminate intercourse … was a source of great suffering to these women.”

Roudanez is best known for his encounters with Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. In late 1863, free men of color met at Economy Hall and crafted a petition demanding the right to vote. Roudanez and Arnold Bertonneau, a former captain in the Louisiana Native Guard, delivered the appeal to the White House on March 12, 1864. Lincoln was impressed with his visitors and quickly asked Louisiana Gov. Michael Hahn to consider limited Black enfranchisement. Hahn ignored Lincoln’s advice.

After leaving the White House, Roudanez spoke with Frederick Douglass. Recalling their conversation, Douglass wrote to Roudanez: “The cause of our race is one, whether at the North or the South—and every upward movement at the South in our behalf is instantly felt here.”

Little is known about Jean Baptiste Roudanez after the demise of the Tribune. Roudanez’s first wife Louise Dauphin died in 1861. His second wife Angela Angelain died in 1866. Roudanez died in New Orleans on November 29, 1895. He is buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, Square 3.