Adams-Onís Treaty

The treaty that settled the western boundary of the Louisiana Purchase was ratified by the governments of Spain and the United States in 1821.

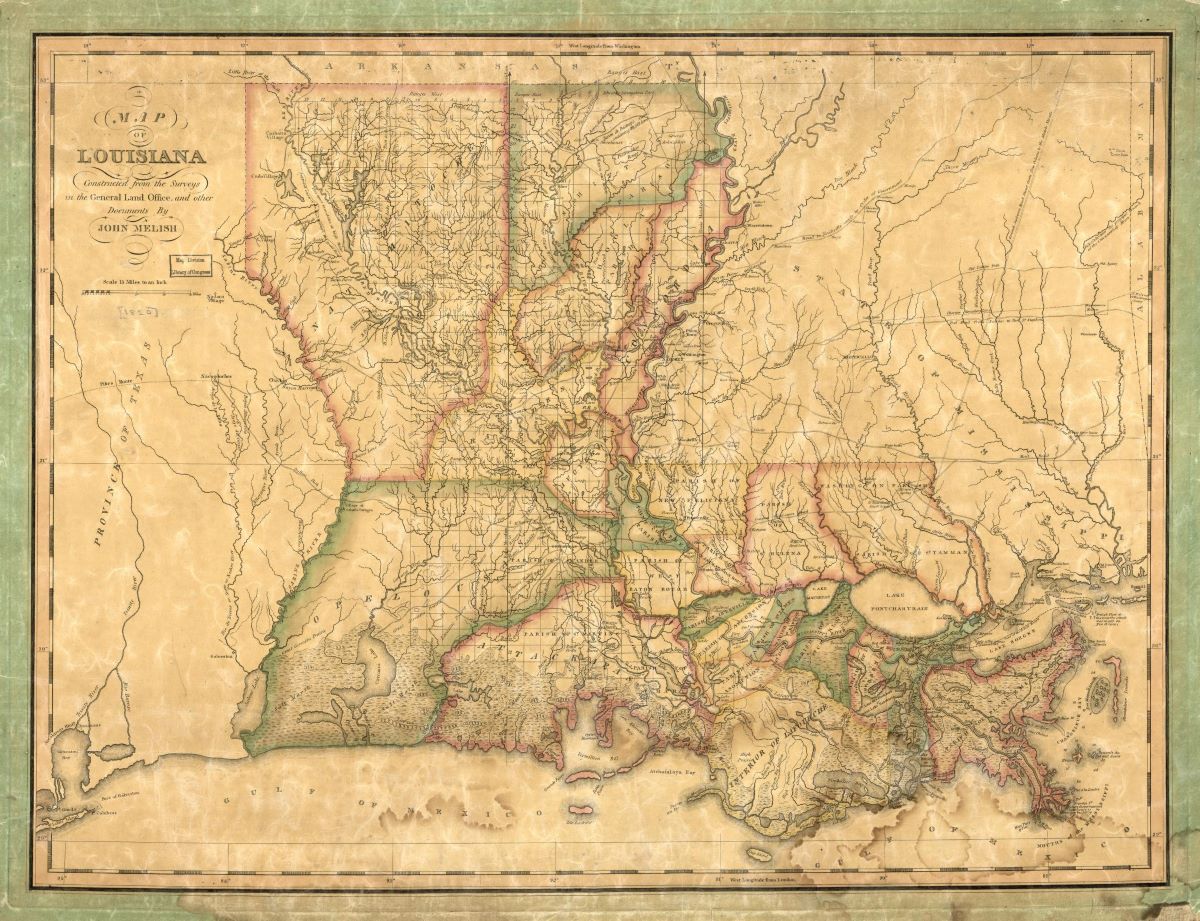

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Map of Louisiana, 1820, by John Melish.

In 1819 the United States agreed with Spain to settle the contested western boundary of the Louisiana Purchase in exchange for the Spanish cession of Florida. By this time Spain and the United States had disputed the exact boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase for more than fifteen years. A previous agreement in 1806 created the Neutral Strip between the Sabine River and the Arroyo Hondo as a temporary solution. US Secretary of State John Quincy Adams brokered a deal to resolve this longstanding dispute with Spanish Ambassador Luis de Onís, a senior diplomat stationed in Philadelphia, who later published a detailed memoir of the negotiations. Also called the Transcontinental Treaty, the agreement was ratified by the US and Spanish governments in 1821 and then hastily renegotiated with Mexico following its independence from Spain a year later.

Colonial Tensions

During the previous fifty years, colonial Louisiana and Florida represented major diplomatic headaches for Spain, which had acquired the former and lost the latter in the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau and 1763 Treaty of Paris. In the case of Florida, Spain abruptly reacquired the colony twenty years later, in 1783, when Britain, unable to defend against the victorious forces of the American Revolution, handed it back to prevent it from falling into American possession. The circumstances of this exchange soured Spanish relations with its new American neighbor in ways that Spain neither wanted nor could afford. Likewise, the expense of administering the former French colony of Louisiana was daunting. Following the success of Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaigns in Italy, in 1800, Spain’s King Charles IV traded Louisiana back to the French via the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso in exchange for lands in Tuscany. Bonaparte sold Louisiana to the United States three years later.

In 1803 none of the colonial powers knew the exact physical extent of the Louisiana Purchase, least of all the buyer, the United States. According to President Thomas Jefferson’s plans, the US Congress appropriated funds to provision a series of joint civilian and military explorational surveys to help identify the Purchase’s boundaries, which went undefined in the treaty itself but were generally agreed to include all the lands east of the continental divide that drained into the Mississippi River. From 1803 to 1808 four separate parties ventured west to help determine physical locations for the boundary line, led by Lewis and Clark on the Missouri River, Dunbar and Hunter on the Ouachita River, Freeman and Custis on the Red River, and Zebulon Pike on the Arkansas River. Wary of the expeditions’ potential proximities to Santa Fe and any American attempts to draw the colony into its economic and diplomatic orbit, and warned by a secret, paid informant (who turned out to be American Gen. James Wilkinson, then serving as the first American governor of the Louisiana Territory), New Spain’s colonial governor dispatched Spanish troops to intercept the American forces. Although eluded by Lewis and Clark, the Spanish troops peacefully halted Freeman and Custis. They also managed to capture (as well as rescue) Pike and his forces, who, in the winter of 1807, got lost in the snowy mountain valleys of present-day Colorado and were starving to death near the headwaters of the Rio Grande.

In 1808 the French conquest of Spain threw colonial affairs into disarray. King Ferdinand VII fled Madrid, and Napoleon installed his brother Joseph as king of Spain. At that time Ferdinand’s ministers dispatched Luis de Onís to Philadelphia with authority to resolve Florida and Louisiana on the king’s behalf in the interest of shoring up American support for the deposed monarch. To maintain the United States’ official neutrality in the Peninsular War, however, American diplomats did not recognize Onís as Spain’s ambassador until news of Napoleon’s defeat and Ferdinand’s restoration finally reached Secretary of State James Monroe in 1815. After being elected to the presidency one year later, Monroe brought in Adams to fill his old role, and Adams continued the work that Onís and Monroe had begun to stabilize the border.

Drawing Boundaries

Like most colonial boundary agreements, though, the eventual treaty Adams and Onís negotiated created new ambiguities even as it resolved old ones. The boundary line began at the mouth of the Sabine River on the Gulf of Mexico, continued upriver to the 32nd degree of latitude, then traveled due north to the Red River, which it followed upriver to the 100th degree of longitude, then again traced due north to the Arkansas River, following that river to its source, upon which it turned westward until reaching the Pacific Ocean. From a practical point of view, only the Sabine and Red River portions mattered to the Americans and the Spanish in 1818 to differentiate the by-then state of Louisiana from the colonial province of Coahuila y Tejas. The treaty was long obsolete by the time either party knew where the Red River existed at the 100th meridian, let alone the location of the Arkansas River headwaters. In fact, it took until a 1930 US Supreme Court decision that followed the decades-long Greer County dispute between Texas and Oklahoma for the precise location of the former to be finally determined. Nevertheless, on today’s map of the United States, the Adams-Onís treaty line remains visible along the boundary between Texas and Louisiana, that of Texas and Arkansas, and the greater part of the Texas and Oklahoma boundary.