Chickasaw Wars

The Chickasaw Wars were a series of proxy wars between the Chickasaws and their British allies in South Carolina and Georgia against French Louisiana and its Native allies, principally from among the Choctaws.

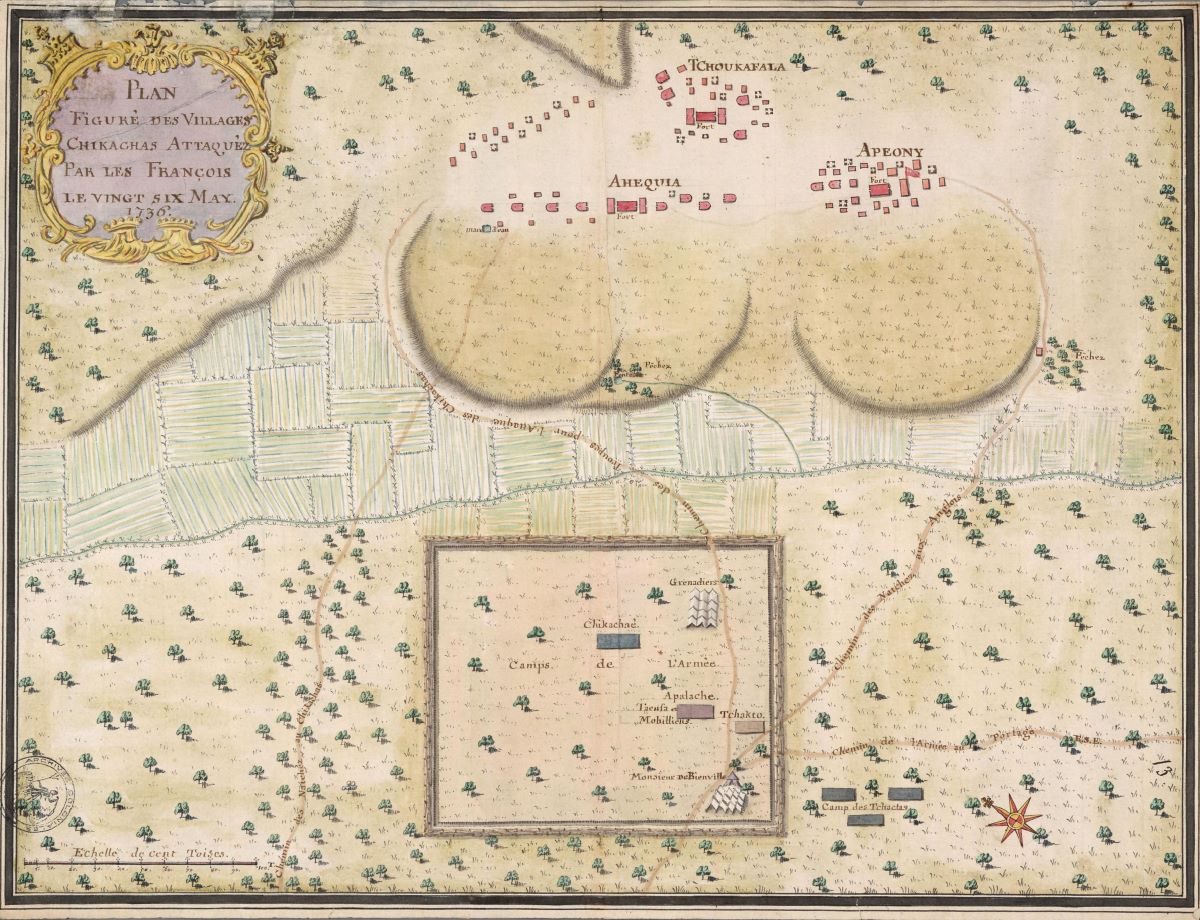

Archives nationales d'outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence, France

Battlefield plan showing three Chickasaw villages attacked by the French and their Indigenous allies on May 26, 1736.

The Chickasaw Wars were a perpetual war from 1721 to 1763 that involved Upper and Lower French Louisiana and its Indigenous allies (principally Choctaw, Quapaw, Illinois or Illiniwek, Miami, Petites Nations, and Iroquois or Haudenosaunee) against Chickasaws, Natchez, and Petites Nations refugees (after 1731), and British trade partners from the colonies of South Carolina and Georgia. Unable to nullify the Chickasaw’s alliance with the British due to chronic trade supply shortages, the French promoted a policy of indirect military intervention where Indigenous proxies engaged in regular raids, ambushes, and skirmishes against Chickasaw towns, hunting parties, and trade and diplomatic missions. Chickasaws retaliated by attacking French convoys moving up and down the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. They launched raids against French outposts and against French Indigenous allies across the Mississippi River valley and as far south and east as the Mobile River. The Chickasaw Wars functioned as a proxy war, which was a conflict wherein non-state actors (Indigenous peoples) were supported, supplied, and encouraged to fight one another by two nation-state actors (colonial powers) without either nation-state directly engaging the other.

Tensions between these antagonists escalated in the 1730s after Chickasaws accepted Natchez refugees fleeing French retaliation in the wake of the Third Natchez War (1729–1731). When Chickasaw leadership refused demands to surrender the Natchez, officials in France ordered them destroyed entirely, prompting two large, European-style conventional military campaigns against their towns in 1736 and 1739. Both campaigns ended disastrously for the French. Sporadic fighting resumed over the next two decades, with the French once again relying heavily on Indigenous allies to attack the Chickasaws until the terms of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau and 1763 Treaty of Paris ceded all French-claimed territory in North America (excluding the island colonies of Saint Pierre and Miquelon) to Spain and Great Britain. Failure to decisively defeat the Chickasaws limited French efforts to exert control over lands and waterways west of the Appalachian Mountains. It also contributed to Great Britain’s ultimate supremacy over North America east of the Mississippi River and Canada until the American Revolution. The wars exacted an enormous human cost and helped precipitate the mutually destructive Choctaw Civil War (1747–1750).

Background

By the end of the seventeenth century, Chickasaw country consisted of about six thousand people living in approximately eighteen towns dispersed across the northern edge of the Black Prairie region in present-day northern Mississippi but with a territorial range that spread into what is now western Tennessee, northeastern Alabama, and southwestern Kentucky. Despite averaging a third the population of their Choctaw, Cherokee, and Creek neighbors, Chickasaws projected outsized influence over the Mississippi River system that linked French settlements on the Gulf of Mexico with New France (Canada) and the vital overland upper and lower trading paths that connected their towns with British ports on the Atlantic Coast. The location proved an opportune and competitive environment—one which provoked a fierce rivalry with northern Indigenous groups such as the French-allied Illinois Confederacy and made Chickasaws alluring allies to the British as they sought to undermine French commercial and colonization efforts on the continent and expand deerskin and captive-taking networks farther inland.

By 1700 Chickasaws exercised a monopoly over the westernmost limits of the commercial Indian slave trade, hastening massive demographic transformations and political realignments among Indigenous societies from the Tombigbee River to the lower Mississippi River valley. Those groups who did not assist Chickasaw depredations as enslavers themselves either fled as refugees into the bayous and deltas along the Gulf Coast and Mississippi River or were incorporated into coalescent societies then taking shape in the interior, such as the Choctaws located in the southern two-thirds of present-day Mississippi. French policy toward Southeastern Woodlands peoples was initially framed in the context of this violence with Pierre Le Moyne, sieur de Iberville, seeking to instill a lasting peace in the broader Mississippi River Valley under French direction. Reconciling the Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Petites Nations people was essential to this plan. Still, it proved unattainable due to the French’s inability to provide dependable and affordable trade in firearms, munitions, cloth, and other manufactures.

Fearful that Choctaws would also be drawn into an alliance with the British and thereby dooming Lower Louisiana, French leadership shifted tactics on February 8, 1721, sanctioning a “bait and bleed” strategy, where Choctaw and Petite Nations warriors were commercially incentivized to kill and capture Chickasaw people in a plan Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, described as not “risking a single Frenchman … to put these barbarians into play against each other, the sole and only way to establish any security in the colony because they will destroy themselves by their own efforts.” Iroquois and Illinois warriors led independent attacks from the north. The protracted hostilities took a tremendous toll and necessitated that Chickasaws fortify and cluster their towns for mutual defense, concentrating in the present-day Tupelo, Mississippi, micropolitan area. Chickasaw peace overtures brought pauses in the fighting over the next decade.

French Campaign of 1736

Chickasaw acceptance of Natchez war refugees in early 1731 provided Louisiana officials with the justification for widening that conflict, with the expressed purpose of eliminating the Natchez and Chickasaws altogether. Bienville understood that to preserve French honor with Indigenous allies such as Choctaws, he needed to commit significant numbers of French soldiers to the effort. By March 1736, he had assembled in Mobile some six hundred French marines and Swiss mercenaries and forty-five enslaved Africans led by free Black officers. From there, Bienville’s force traveled by boat some 270 miles up the Tombigbee River, disembarking near present-day Epes, Alabama, where they began constructing the stockaded trade depot Fort Tombecbé. The plan was to link up with an equal number of Choctaws and form the southern pincer of a two-pronged invasion of Chickasaw country in coordination with another 145 French soldiers and some 326 Iroquois, Quapaw, Illinois, and Miami auxiliaries from Upper Louisiana led by Pierre Dartaguette. Beset with delays and hindered by poor communication, Bienville was unaware that Dartaguette’s force was annihilated in its assault on the Chickasaw town of Ogoula Tchetoka weeks before Bienville’s arrival in Chickasaw country. Bienville’s own force was routed outside the heavily fortified Chickasaw town of Ackia on May 26, 1736.

French Campaign of 1739

Bienville immediately prepared for a second, larger invasion of Chickasaw country from Upper and Lower Louisiana with double the numbers of French marines and Indigenous auxiliaries, this time equipped with cannons and other siege engines to breach Chickasaw fortifications. The two armies arrived near present-day Memphis, Tennessee, in July and August 1739. However, the mission came to a halt by winter, hampered by disease, weather, logistical problems, mass desertions from Indigenous allies, and difficult terrain. Despite these setbacks Chickasaws extended peace offers. With the cost of the expedition having already exceeded three times the operating budget for the entire colony, and learning that the Natchez had largely resettled farther east among the Creek and Cherokee peoples, Bienville accepted terms and withdrew what was left of his army. However, attacks from French-allied Choctaws against the Chickasaws resumed within a few months and would continue until the 1760s. Years of fighting and French failure to provide a consistent trade in goods and weapons at comparable prices to the British contributed to internal divisions within Choctaw society that led to the destructive Choctaw Civil War from 1747 to 1750.