Immigrants in Civil War New Orleans

During the Civil War, immigrant communities in New Orleans generally supported the Union cause.

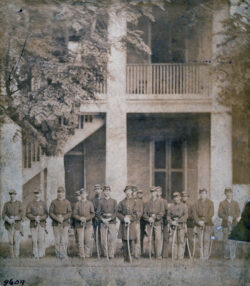

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

German cavalry at Jackson Barracks. Unidentified

On the eve of the Civil War, New Orleans was a polyglot of Creoles, Anglo-Americans, free people of color (gens de couleur libres), slaves, and immigrants from all over the globe. In a population of 170,000 people, roughly 70,000 were immigrants, and foreign-born Irish and Germans alone made up a quarter of the population.

While earlier Irish immigrants belonged to the urban professional class, the “famine Irish” of the late 1840s and 1850s—desperate and uneducated—served as an unskilled labor force on canals, levees, and docks. The Germans, political refugees from the failed revolutions of 1848, were mostly shopkeepers and artisans. Both groups incurred the abuse of nativist Anglo-Americans who controlled New Orleans politics from 1854 through federal occupation in May of 1862. Largely ambivalent toward slavery and secession, and supported by Union generals Benjamin Butler and Nathaniel Banks, it was the Irish and Germans who formed the rank and file of a New Orleans pro-Union movement, culminating in the election of German immigrant Michael Hahn as governor of occupied Louisiana in 1864.

After the federal occupation of New Orleans on May 1, 1862, the pro-Irish True Delta commented, “For seven years past the world knows that this city in all its departments…has been at the absolute disposal of the most godless, brutal, ignorant, and ruthless ruffianism the world has ever heard of.” The ruffianism was an allusion to the mayor of New Orleans, John Monroe, and his American Party (also known as the Know-Nothing Party), which controlled New Orleans politics from 1854 through occupation. The American Party, a national third party, freely used violence and intimidation to curtail the Irish and German immigrant vote and endorsed immigration restrictions and anti-Catholic legislation. Historians attribute the rise of the Know-Nothing Party in heavily Catholic New Orleans to the Anglo-American population trying to wrest control of the city from the old Creole regime. By eschewing the anti-Catholic prejudice of the national party, the local American Party even attracted some Creole elites, even though the immigrants tended to vote Democratic and therefore support Creole candidates. Nevertheless, because of this intimidation immigrant voting was negligible in the elections of 1856 and 1860. The city administration also effectively denied immigrants civil service posts, and the percentage of Irish and German policemen declined from 32 to 11 percent and 16 to 3 percent respectively during this period.

After Union occupation, Gen. Benjamin Butler and his successor Nathaniel Banks recruited 4,000 white Union troops from New Orleans, mostly of immigrant stock. Many who served at Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip had been forced into the Louisiana militia: after Admiral David Farragut’s Union fleet steamed past the forts, scores deserted and enlisted in the Union army, according to the Confederate commander J. Kelly Duncan. Regimental histories reveal that those New Orleanians who deserted the Confederate Army and served in Union regiments were overwhelmingly of foreign birth or had lived in northern states. Although historians generally attribute this trend to economic necessity, the fact that Mayor John Monroe’s regime was anti-immigrant and pro-Confederate suggests that many enlistments were made out of conviction. After occupation, a unionist asked Butler to rid the city of a “Know-Nothing rebel mayor and his police of cutthroats.” By assimilating troops into existing units, such as the Irish Ninth Connecticut, Butler formed two new regiments of immigrant volunteers to bolster his relatively small force of 14,000 troops.

Nevertheless, New Orleans was a Confederate city before occupation, and of the 20,000 troops who enlisted from New Orleans in the Confederate army and its environs, a third were of foreign birth. The fact that New Orleans unionist volunteers and supporters of the Free State Movement (a war-time effort to restore Louisiana to the Union) were largely working class and immigrant evinces attitudes at odds with the native-born population of the city. While the immigrant population can hardly be characterized as abolitionist, there was genuine class resentment against slaveholders stemming back to Ireland and the German states, where aristocratic privilege and institutions continued to flourish. This did not mean sympathy for the slave—as Ira Berlin and Herbert Gutman noted, this resentment extended to the slave as well: “Hatred of slavery and the slave frequently became one.” The political dominance of the planter class and the competition of slave labor threatened both immigrant and native-born labor. As Eric Arnesen has argued, by the time of the Civil War, New Orleans’ “craft workers saw their political and economic opportunities eclipsed by slavery and slave owners.”

As a Jacksonian Democrat, the much-maligned Benjamin Butler was acutely aware of this resentment and successfully exploited it. Upon occupying the city, he sought to punish the wealthy, whom he blamed for the war, through aggressive taxation. With a reference to Know Nothing violence, he exempted from taxes the working class, who had “never been heard at the ballot box, unawed by threat, and unmenaced by thugs.” He issued General Order 25, putting 2,000 men to work cleaning the city at 50 cents a day. He later issued General Order 55, which put 11,000 families on relief. Some 80 percent of families who received assistance from Butler’s U.S. Relief Commission were immigrant families, predominately Irish and German. When Butler required residents of New Orleans to take an oath of allegiance to the Union, it was the “bone and sinew of the city” who first took the oath. At the end of Butler’s tenure, a torchlight procession of 300 workers thanked Major General Butler “for the kind of interest he has taken in the laboring classes … for other wise we would have been compelled to join the so-called Confederate army or starve in a Confederate prison.”

Like his predecessor, Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks wanted to build a New Orleans unionist movement by drawing on immigrant and native-born labor. He supported the formation of the Working Men’s National League, essentially a working-class appendage to the Free State Movement. The Working Men’s National League convention of 1863 called for the abolition of slavery, removal of the economically powerful free people of color as well as the ex-slaves from the state of Louisiana, and universal white male suffrage without a residence requirement. Resentment against slavery, free black labor, and Know-Nothingism could now be expressed under Banks’s protection.

Michael Hahn

Immigrant and native-born workers elected Michael Hahn to Congress in 1862. Hahn had emigrated from Bavaria in 1840 and earned a law degree from the University of Louisiana (present-day Tulane University) in 1851. Hahn was a quintessential nineteenth-century liberal who believed that education and democratic government were avenues that led to social progress. Even though Congress nullified the election, Hahn had launched a public career and ran for wartime governor in 1863. Hahn was undisputedly a man of courage; he refused to take a loyalty oath to the Confederacy when many unionists fled the city, and he suffered severe wounds in the New Orleans Riot of 1866 for endorsing black suffrage. In 1863, he crafted a position in line with his working-class, immigrant constituency. In a speech to the Union Association of New Orleans at Lyceum Hall, he posed the question, “Why should a man, because he owns a plantation and slaves, have greater political rights than other men who have no such profitable investments?” Foreshadowing later-nineteenth-century populism, Hahn accused the Louisiana antebellum legislature of concerning themselves exclusively with the “interests of slavery,” rather than “paying some attention to the poorer and industrious classes of our citizens.”

Hahn appealed to immigrant labor by exploiting racial tensions. Francis Boisdore, a well-known free black leader, had earlier called for black suffrage, after charging that “illiterate Germans and Irishman” had the franchise. Hahn responded by referring to Boisdore as a “colored Know Nothing,” asserted that local Germans were indeed educated, and observed that while the “oppression of the British government” had deprived the Irish of an education, “their vivacity, activity, wit and intelligence is proverbial.” Hahn’s claim that Irish and German blood had “been freely and nobly shed” on the battlefield could not have gone unnoticed by the free black community who had suffered prodigious causalities for the Union cause.

Gen. Nathaniel Banks, who had served as the Know Nothing governor of Massachusetts, saw the immigrant Hahn as the best hope for restoring Louisiana to the Union. In the gubernatorial election of 1864, Banks endorsed Hahn over the conservative J. Q. A. Fellows and the radical Benjamin Flanders. Hahn’s plan to break the planter elite through emancipation and expand the franchise for white labor won the support of the Working Men’s National Union League, the Mechanic’s Association, the Crescent City Butcher’s Association, the Working Men of Louisiana, and the German Union. Hahn won the election with 54 percent of the vote in a three-man race. Even though the results included only occupied Louisiana and votes totaled just 20 percent of Louisiana’s 1860 vote, it is significant that Hahn won 62 percent of the New Orleans vote. In what would have been unthinkable before the war, New Orleans politics came to be dominated by a heretofore-disfranchised group.