Judaism in Louisiana

Jewish people have greatly contributed to Louisiana’s culture and economy as philanthropists, civic and educational leaders, business owners, and art patrons.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

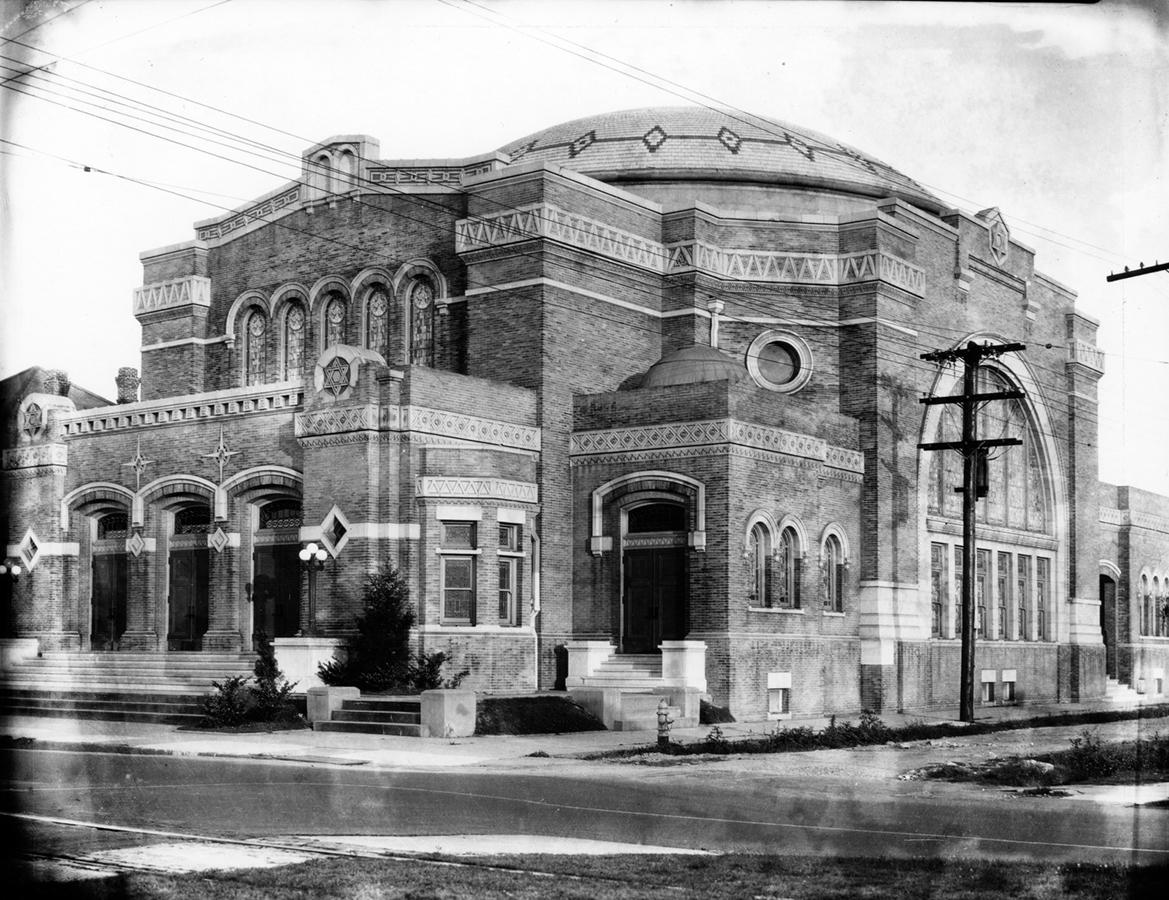

Touro Synagogue on St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans, ca. 1914–1924. Charles L. Franck Photographers; Nancy Ewing Miner, photographer.

While Jewish people have made up only about one percent of Louisiana’s population since Reconstruction (and far less than that before the Civil War), they have had a significant impact on the state’s economic, educational, and civic development. Jewish people in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Louisiana tended to be more urban than the general population and often established the first retail establishments in towns like Lake Charles, Shreveport, and Alexandria. Jewish families were also generous philanthropists, and some Jewish leaders became activists on behalf of greater civil liberties. While Jewish people benefited from white supremacy and some were ardent segregationists, many Jewish people were politically progressive and advocated ending discriminatory practices based on race, religion, gender, and nationality in favor of expanded opportunities for many Americans. Louisiana Jewish communities preserved their religious traditions even as they acculturated into the dominant Christian culture. As of 2017 Louisiana’s Jewish population was approximately 13,900 people.

Jewish Ethnic Identity

Jewish people who emigrated to Louisiana during the colonial and antebellum periods typically came from Western and Central Europe, mostly from Germany. They disembarked in New Orleans, where many stayed and established synagogues and businesses. The first Jewish congregation anywhere in the Mississippi Valley south of Cincinnati, Gates of Mercy, was founded in 1827 in New Orleans. By 1842 there were about two thousand Jewish people living in New Orleans, and, like most other elite white Louisianans in the antebellum period, they often owned enslaved people. Some Jewish people became plantation owners and amassed large enslaved workforces. US Senator Judah P. Benjamin, who enslaved 140 people, was the largest Jewish slaveholder in the United States. Like most other Jewish people in Louisiana at the time, he supported the Confederacy’s cause, and even served as a cabinet official in the Confederate government during the Civil War.

A common pattern of settlement was for Jewish immigrants to land first in a port of entry like New Orleans, stay there for a bit, and then fan out into the interior looking for entrepreneurial opportunities in small towns that, after 1865, were struggling to recover from the Civil War. German Jewish migration continued to predominate among Jewish newcomers in at least some small communities in the final decades of the nineteenth century. After 1881 Jewish immigrants came from Eastern Europe fleeing poverty, persecution, harassment, and state-sanctioned violence known as pogroms—organized massacres that targeted Jewish communities—fueled by anti-Semitism in the Russian Empire following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. By the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, Eastern Europeans made up the bulk of the Jewish population in Louisiana’s smaller communities.

Different Styles of Religious Observance

Judaism in the United States, like Protestantism, experienced divisions about the proper form of worship and other matters of Jewish cultural identity. Jewish people of German descent tended towards Reform Judaism, a product of the Enlightenment that de-emphasized traditional Jewish practices. The denomination ended strict observance of dietary laws, replaced segregated seating for men and women with family seating, and exchanged the traditional cantor (or musical leader) for congregational choirs. In Reform congregations, rabbis preached in the vernacular, and Hebrew prayers were translated into English. Reform temple architecture tended to mimic Protestant churches that surrounded them, which helped these congregations blend into the dominant culture. The first Reform temple in Louisiana was New Orleans’s Touro Synagogue, founded in 1870.

Horrified by what they considered the sacrilege of Reform Judaism, Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants established Orthodox congregations in larger communities like New Orleans, Shreveport, and Alexandria. But their numbers were so much smaller in New Orleans than the German Jewish population, that Reform congregations outnumbered the others two to one in the Crescent City. In 2023 there were at least two Chabad (Hassidic) congregations operating in New Orleans.

Another conflict among different Jewish adherents surfaced over the role of women in temple life. While Reform and Conservative denominations began to allow women to serve as rabbis in the twentieth century, Orthodox sects still do not allow women to enter the rabbinate. As of 2023 women rabbis have served or are serving some of the major congregations in Louisiana—Touro in New Orleans and Unified Jewish Congregation in Baton Rouge—as well as smaller ones.

Jewish Economic Contributions

Since Jewish people rarely owned land in Europe, they had little experience with farming, and most supported themselves through entrepreneurial activity or trade. These skills proved highly valuable in Louisiana, which, after the devastation of the Civil War, was in desperate need of them. After a few years as independent peddlers or tradesmen, Jewish entrepreneurs often acquired enough capital to purchase buildings and real estate. They opened retail stores such as Godchaux’s, Maison Blanche, Muller’s, and Riff’s and founded banks in small towns across Louisiana, many of which were the first such financial establishments those towns had ever seen. These Jewish migrants thus provided badly needed services throughout the state. Jewish entrepreneurs were helpful to the commerce of rural areas, too. For example, Abrom Kaplan (for whom the town of Kaplan is named) played a key role in modernizing south Louisiana’s rice production.

Civic Engagement and Philanthropy

Jewish citizens were among the most generous donors in their adopted communities. In New Orleans, like other groups of immigrants, Jewish men and women established charitable organizations to assist their co-religionists. These organizations included the Jewish Widows and Orphans Home and Touro Infirmary. Jewish philanthropy also benefited schools, universities, museums, and public spaces. Jewish families supported Tulane University, from which many had graduated. Tulane, unlike virtually every other institution of higher learning in the United States, did not have a quota system that limited Jewish enrollment, and it therefore attracted Jewish students from around the country.

Jewish women established the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Associations, which had the goal of “alleviating want and suffering” not just among fellow Jewish people but for non-Jewish people, too, especially during times of crisis such as when epidemics or natural disasters hit. The National Council of Jewish Women, which was dedicated to “religion, philanthropy, and education,” had chapters in several larger Louisiana communities. Like men, Jewish women also formed chapters of B’nai B’rith (a service organization dedicated to combating anti-Semitism), supported secular organizations such as the Community Chest, battered women’s shelters, AIDS councils, nonprofit counseling centers, and other benevolent organizations dedicated to assisting those in need.

Anti-Semitism

Jewish people tended to find little anti-Semitism in Louisiana because, at the time, their whiteness mattered more than their ethnic background. However, as time went on and nationalism reared its head in the United States as in Europe, doors that had once been open to them began to close. This was particularly true after 1881, when Eastern European Jewish people arrived in large numbers. The rising tide of immigration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the United States increased xenophobia, and for the first time in the 1880s, New Orleans’s exclusive clubs (such as the Louisiana Club, the Country Club, and Mardi Gras krewes) began to prohibit Jewish membership.

The ban on Jewish people entering elite clubs and carnival krewes in New Orleans was maintained until the City Council passed a controversial ordinance in 1992, sponsored by Councilwoman Dorothy Mae Taylor, that prohibited any club that discriminated based on race or ethnicity from getting a permit to parade on city streets or a liquor license. That same year, former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, who had made successful bids for the state legislature in the 1980s, ran for governor against Edwin Edwards. Duke’s gubernatorial run was thwarted by activists organized against him, including Holocaust survivor Anne Levy.

To counter overt discrimination, Jewish citizens created their own separate institutions and clubs, such as B’nai B’rith, the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, and, in more recent years, Mardi Gras krewes. They also dealt with exclusion by focusing their time and money on charitable, cultural, and civic institutions as a way of proving they could both maintain their Jewish cultural identity and be good citizens in an overwhelmingly Christian country.

Acculturation

Acculturation, the process by which Jewish people adapted to American life by borrowing traits of the dominant culture, created some difficulties for Jewish identity, particularly outside New Orleans, where there were relatively few Jewish families. Their children attended local schools and became friends with Catholic and Protestant children. They went to secular colleges, married Protestants or Catholics, and, especially in the years after World War II, expressed little interest in taking over family businesses. Second- and third-generation Jewish citizens instead adopted careers that took them far away from home. As a result, the Jewish population declined in small cities and towns in the second half of the twentieth century, and New Orleans remained the center of Jewish life in the state.

To try to stem the assimilationist tide, Jewish families sought opportunities to cultivate friendships with other Jewish families in communities elsewhere in Louisiana or in neighboring states. They sent children to Jewish summer camps for much the same reason. Likewise, Jewish women formed Temple Sisterhoods. Though sisterhoods raised money for the upkeep and maintenance of the temple and its grounds, their primary mission was “to raise Jewish people.” Women taught Sunday schools to educate their children in Judaism, and they kept alive religious home observance to help prevent children from turning away from faith traditions.

Activism

Many Jewish Americans, particularly the generation that immigrated to the United States after 1880, supported liberal causes such as welfare rights, liberal immigration policies, women’s rights, and equal educational opportunities regardless of race or ethnicity, all goals that aligned with their own interests as a community. Reform Judaism’s prophetic legacy insisted that Jewish people play a role in creating a better, more equitable world free from discrimination based on race or ethnicity. This also included defending the concept of separation of church and state. In a case against the Caddo Parish School Board in 1915, Jewish parents Henry Heilperin and Sidney Herold, a Shreveport attorney, and Catholic parent James Marston won a successful ruling from the Louisiana Supreme Court saying that requiring students to read a Protestant Bible (the King James Version) and pray a Christian prayer (the Lord’s Prayer) violated the state’s constitutional guarantee of religious liberty. Several of the attorneys who founded the Louisiana chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union in the 1950s were Jewish.

In addition to the American Civil Liberties Union, some Jewish citizens in Louisiana championed civil liberties in other intergroup alliances like the Urban League and the NAACP. The Jewish Labor Committee defended the rights of both Black and white workers to organize and bargain collectively. Jewish attorneys represented labor unions such as the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Likewise, women in the Temple Sisterhoods joined the League of Women Voters, and, when the modern women’s rights movement emerged in the 1970s, Jewish women were among the most active supporters of the National Organization for Women and other feminist organizations.

Jewish Americans were not uniformly liberal, however, and it is important to note that Jewish community politics were affected by local conditions. Southern Jewish people, like other white southerners, were privileged by whiteness, and sometimes this meant that they accommodated themselves to the racial status quo. During the civil rights struggle in the 1950s and 1960s, while a few Jewish leaders in Louisiana stood together in solidarity with African Americans, others, fearing retribution and backlash, remained silent and thus tacitly complicit with the Jim Crow system from which they benefited.

Conclusion

Today Jewish people in Louisiana’s smaller urban centers sometimes struggle to keep their temples open and retain their cultural identity, as they make up a small percentage of the population. Many Jewish Louisianans have made compromises with the dominant Christian culture to maintain some aspects of their religious identity. Regardless, Jewish people have had an outsized impact on Louisiana’s culture and economy through centuries of contributions as philanthropists, civic and educational leaders, business owners, and art patrons.