Leander Perez

Corrupt democratic politician Leander Perez Sr., a staunch segregationist, served as a district judge, district attorney, and president of the Plaquemines Parish Commission Council.

This entry is 8th Grade level View Full Entry

Robert Winans

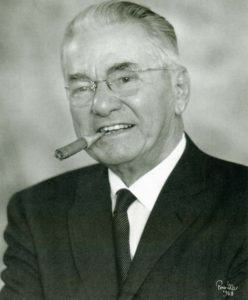

Leander Perez, 1968.

Leander Henry Perez was a powerful political leader who ruled Plaquemines Parish for five decades, from the 1920s through the 1960s. In addition to being a millionaire oil speculator, Perez also became an ally of fellow outspoken white supremacists of his time, such as Strom Thurmond, Lester Maddox, and George Wallace.

What was Leander Perez’s early life and career like?

Perez was born on July 16, 1891, in the village of Dalcour in Plaquemines Parish to Gertrude Solis Perez and Roselins E. “Fice” Perez, a prosperous sugar and rice planter and longtime member of the Lafourche Basin Levee District. He attended Holy Cross boarding school in New Orleans and Louisiana State University. He received his law degree from Tulane University in 1914. Perez and his wife Agnes Chalin had four children.

In 1919 Perez was appointed district judge for Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parishes and was reelected to a full term in 1920. As a result, he was commonly known as “Judge.” Four years later he was elected to the position of district attorney. Perez’s career was characterized by two themes: race and power. Throughout his political career, he exercised considerable control over his constituents and destroyed all his opponents. Rather than relying on taxes to finance schools, roads, and recreation facilities, he created a miniature welfare state for Plaquemines Parish by leveraging the parish’s mineral wealth. Residents of the parish, which straddles the winding final stretch of the Mississippi River before it empties into the Gulf of Mexico, relied on his generosity. Many genuinely admired him.

In 1928 Perez joined forces with Huey Long, the newly elected governor, and acted as the defense attorney during Long’s 1929 impeachment trial, which was largely motivated by Standard Oil’s concerns over Long’s direct taxation of refined oil. As a result, legislation passed that permitted Perez to use oil on public lands for personal gain. To make his fortune, Perez set up dummy corporations, like Delta Development, which acquired and traded oil leases for huge profits.

Perez initially supported the entrenched Long political machine after the governor was assassinated in 1935. Perez faced a significant challenge in 1940 when one of his archenemies, Sam Jones, an anti-Long politician, won the election for governor. It was Jones who created the State Crime Commission, which compiled evidence against Perez. However, the commission was declared unconstitutional before it could take any action. In 1943 when Jones ordered the National Guard to invade Plaquemines Parish to enforce the installation of a state-appointed interim sheriff, Perez organized a mob of men in the parish, including American Legion members, who built and ignited a roadblock of gasoline-soaked oyster shells to thwart Jones’s action. In response, Perez fled by boat to Mississippi, where he filed fifteen lawsuits at once. In the end he was able to regain power through an election. Following the election of Jimmie Davis as governor in 1944, Perez, who hadn’t initially supported the country singer, formed an alliance with him. Perez supported Earl Long’s candidacy in 1948, but the two men had a falling out shortly thereafter. Despite Perez’s opposition, Long won a third term in 1956, but in 1960, Perez’s friend Davis returned to power.

How did Perez influence Plaquemines Parish and Louisiana?

Perez played a pivotal role in denying Louisiana its potential share of offshore oil lease revenues during the administration of President Harry Truman. In 1948 Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, serving as Truman’s emissary, met with Perez and other Louisiana officials in Washington and proposed a deal to provide two-thirds of all revenue generated by mineral bonuses, leases, and royalties within a three-mile band from the Louisiana coastline into the Gulf of Mexico, and 37.5 percent of all revenue generated by tidelands outside of this boundary to the state. According to Truman’s Continental Shelf Proclamation of 1945, the federal government is responsible for all offshore resources, but members of Truman’s administration were willing to negotiate with Gulf states that were most affected by offshore oil drilling. Rayburn’s offer was flatly rejected by Perez, acting out of personal interests arising from his lucrative leases in Plaquemines Parish. He promised to urge Governor Earl Long to reject the revenue-sharing compromise. By threatening to remove Long’s nephew Russell, Huey’s son and a candidate for the US Senate, from the States’ Rights ticket, Perez prevailed upon Long to reject Rayburn’s offer, effectively handing the election to Shreveport Republican Clem Clarke. Ultimately Long yielded to Perez’s pressure and declined the proposal. On June 5, 1950, the US Supreme Court ruled that all submerged land from the shores of coastal states belonged to the federal government, not to the states, because the federal government claimed sovereignty over all mineral resources beneath the oceans. The estimated loss to Louisiana over the course of nearly seven decades has been calculated at more than $100 billion.

How did Perez resist desegregation?

Perez devoted a considerable amount of his energy and fortune from the 1940s until his death in 1969 to preserving racial segregation. He supported the 1948 Dixiecrat presidential campaign of South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, whose message of strict segregation of the races won the majority vote in Louisiana. Perez considered integration to be a Communist scheme intended to encourage racial mixing. He testified before congressional committees opposing civil rights bills, authored state segregation laws, and fought federal legislation in court. He helped organize the Citizens’ Council of Greater New Orleans to prevent desegregation and spoke vehemently against the enrollment of four Black girls, Ruby Bridges, Tessie Prevost, Gail Etienne, and Leona Tate, in two public schools. His calls for resistance to desegregation in New Orleans led to violent protests. And in Plaquemines Parish Perez sought to get around desegregation laws by closing public schools and opening all-white private academies.

In April 1962 Archbishop Joseph Francis Rummel excommunicated Perez from the Catholic Church for ignoring a warning to stop obstructing efforts to integrate schools run by the Archdiocese of New Orleans. In 1964 Perez strung barbed wire around Fort St. Philip, an abandoned nineteenth-century military outpost along the Mississippi River, and promised to jail civil rights activists in the snake-infested, makeshift prison if they dared stir up trouble in his parish. However, no one was ever imprisoned there. Plaquemines Parish eventually yielded, grudgingly, and desegregated its schools in 1967.

As chair of the Democratic State Central Committee, Perez attempted to deny Louisiana’s electoral votes to liberal candidates. To oppose Louisiana’s vote for John F. Kennedy in 1960, he created a slate of unpledged electors. In 1964 he backed George Wallace, whose rallying cry was “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” until the Alabama governor withdrew in favor of Republican Barry Goldwater, who carried Louisiana. In 1968 Perez again backed Wallace, who won Louisiana. When it came to state and national elections, Plaquemines cast very few votes, but Perez was able to deliver them in bulk. The parish-wide vote was virtually unanimous due to respect for Perez and suppression of the Black vote.

Perez retired as district attorney in 1961 and became president of the new parish commission council. Lea, his son, became the district attorney. Perez retired as president of the commission council in November 1967, and his son Chalin succeeded him. At seventy-six Perez suffered a heart attack in January 1969, appeared to recover, but died of a second heart attack on March 19. The Perez family dynasty was ultimately ended by a feud between his sons.