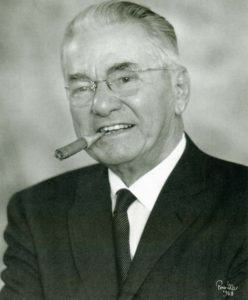

Leander Perez

Corrupt democratic politician Leander Perez Sr., a staunch segregationist, served as a district judge, district attorney, and president of the Plaquemines Parish Commission Council.

Courtesy of Robert Winans

Leander Perez, 1968. Fonville Winans (photographer) Leander Perez (subject)

“Judge” Leander Henry Perez was one of the most powerful political bosses in American history, ruling Plaquemines Parish with absolute control for five decades, from the 1920s through the 1960s. A millionaire oil speculator, he rose to power as a race-baiting southern political leader, becoming a virtual dictator and an ally of fellow outspoken white supremacists of his era, including George Wallace, Strom Thurmond, and Lester Maddox.

Perez was born on July 16, 1891, in the village of Dalcour in Plaquemines Parish to Gertrude Solis Perez and Roselins E. “Fice” Perez, a prosperous sugar and rice planter and longtime member of the Lafourche Basin Levee District. He was educated at Holy Cross boarding school in New Orleans and Louisiana State University, which he attended from 1906 to 1912. He received his law degree from Tulane University in 1914. Perez married Agnes Chalin in 1917, and the couple had two sons, Chalin and Leander “Lea” Jr., and two daughters, Joyce and Betty.

Louisiana Political Career

In 1919 Perez was appointed district judge for Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parishes and was reelected to a full term in 1920. He was henceforth known as “Judge.” Four years later he won election as district attorney. There were two themes in Perez’s career: race and power. He exercised dominion over his constituents and crushed all opponents. He attained this unassailable status by way of creating a miniature welfare state for Plaquemines Parish, with schools, roads, and recreational facilities financed by the parish’s mineral wealth rather than taxation. The impoverished residents of the parish, which flanks the meandering final stretch of the Mississippi River before it empties into the Gulf of Mexico, relied on his benevolence and many genuinely admired him.

In 1928 Perez teamed with Huey Long, the newly elected governor, and in 1929 acted as a defense attorney during Long’s impeachment, a legislative trial largely motivated by interests at Standard Oil in retaliation for Long’s taxation of refined oil. Perez was rewarded with legislation permitting him to exploit oil on public lands for personal gain. He set up dummy corporations, such as Delta Development, that acquired and traded leases for enormous profits, which became the source of Perez’s fortune.

After Long’s assassination in 1935, Perez initially supported the entrenched Long machine. In 1940 Perez faced a major challenge with the election of one of his archenemies, Gov. Sam Jones, an anti-Long politician. Jones created the State Crime Commission, which compiled evidence against Perez, yet the commission was declared unconstitutional before it could act. In 1943, when Jones ordered the National Guard to invade Plaquemines Parish to enforce installation of a state-appointed interim sheriff, Perez marshaled a mob of men in the parish, including members of the American Legion, who built and ignited a roadblock of gasoline-soaked oyster shells in an attempt to turn back the appointee. Perez then fled by boat to Mississippi, where he fired off a string of lawsuits (fifteen at one time). He ultimately regained power in an election. When Jimmie Davis succeeded Jones in 1944, Perez, who had not initially supported the country singer-turned-governor, forged an alliance. In 1948 the Plaquemines boss supported the candidacy of Earl Long, who won, but the two men soon parted ways. In 1956 Long won a third term over Perez’s opposition, but in 1960 Perez’s friend Davis returned to office.

Perez played a pivotal role in a decision during President Harry Truman’s administration that denied Louisiana its potential share of revenue from offshore oil leases. In 1948 Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, serving as Truman’s emissary, met with Perez and other Louisiana officials in Washington and offered a deal to give the state two-thirds of all revenues accruing from mineral bonuses, leases, and royalties in a three-mile band extending from the Louisiana coastline outward into the Gulf of Mexico, and 37.5 percent of all revenues in the tidelands outside this boundary. Truman, in his Continental Shelf Proclamation of 1945, had declared that the federal government had jurisdiction over all offshore resources, but the president was willing to bargain with Gulf states most affected by the emerging offshore oil-drilling industry. Perez, acting out of personal interests from his lucrative leases in Plaquemines Parish, flatly refused Rayburn’s offer and told the speaker that he would encourage Gov. Earl Long to reject the revenue-sharing compromise. Perez prevailed upon Long to turn down the deal and threatened to take Long’s nephew Russell, Huey’s son and a candidate for US Senate, off the States’ Rights ticket, virtually handing the election to Shreveport Republican Clem Clarke, if Long accepted Rayburn’s offer. Caving to Perez’s arm twisting, Long turned down the proposal. The federal government subsequently filed suit against Texas and Louisiana, claiming sovereignty over all mineral resources beneath oceans, and on June 5, 1950, the US Supreme Court ruled that all submerged land from the shores of coastal states belonged not to the states, but to the federal government. The estimated loss to Louisiana over the course of nearly seven decades has been calculated at $100 billion.

The Segregation Crusade

From the late 1940s onward, Perez devoted much of his energy and fortune to preserving racial segregation. He helped bankroll the Dixiecrat presidential campaign of South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond in 1948, and Thurmond’s message of strict separation of the races won the majority vote in Louisiana. Perez considered integration a Communist scheme to encourage miscegenation. He testified before congressional committees against civil rights bills, authored state segregation laws, and fought federal legislation in court. He helped organize the Citizens Council of Greater New Orleans to prevent desegregation and spoke vehemently against the enrollment of four African American girls in two public schools: “Are you going to wait until Congolese rape your daughters! Are you going to let these burr-heads into your schools! Do something about it now!”

In April 1962 Archbishop Joseph Francis Rummel excommunicated Perez from the Catholic Church for ignoring a warning to cease obstructing desegregation. In 1964 Perez strung barbed wire around a long-abandoned nineteenth-century military outpost, Fort St. Philip, and promised to jail “outside agitators” in the Civil Rights Movement in this snake-infested makeshift prison if they dared to stir up trouble in his parish. None did, and the prison was never used. Plaquemines Parish yielded grudgingly, and its schools were desegregated in 1967.

On the presidential level, Perez, as chair of the Democratic State Central Committee, attempted to deny Louisiana’s electoral votes to liberal candidates. In 1960 he created a slate of unpledged electors in defiance of Louisiana’s vote for John F. Kennedy. In 1964 he backed George Wallace, until the Alabama governor withdrew in favor of Republican Barry Goldwater, who carried Louisiana. In 1968 Perez backed Wallace, who won Louisiana. He donated large sums to conservative candidates, campaigning chiefly in Louisiana. In state and national elections, Plaquemines cast few votes, but Perez could deliver them in a bloc. There was virtual unanimity in the parishwide vote—a combination of respect for Perez and voter fraud.

Perez’s Final Years and His Successors

In 1961 Perez retired as district attorney and became president of the new parish commission council. His son Lea became district attorney. In November 1967 Perez retired as commission council president and was succeeded by his son Chalin. In January 1969 Perez suffered a heart attack, seemed to recover, then died of a second attack on March 19 at the age of seventy-six. Eventually, a feud between his sons ended the Perez family dynasty.