Oliver Pollock

Irish-born merchant Oliver Pollock helped finance the American Revolution using profits from trading in dry goods, military supplies, and enslaved people.

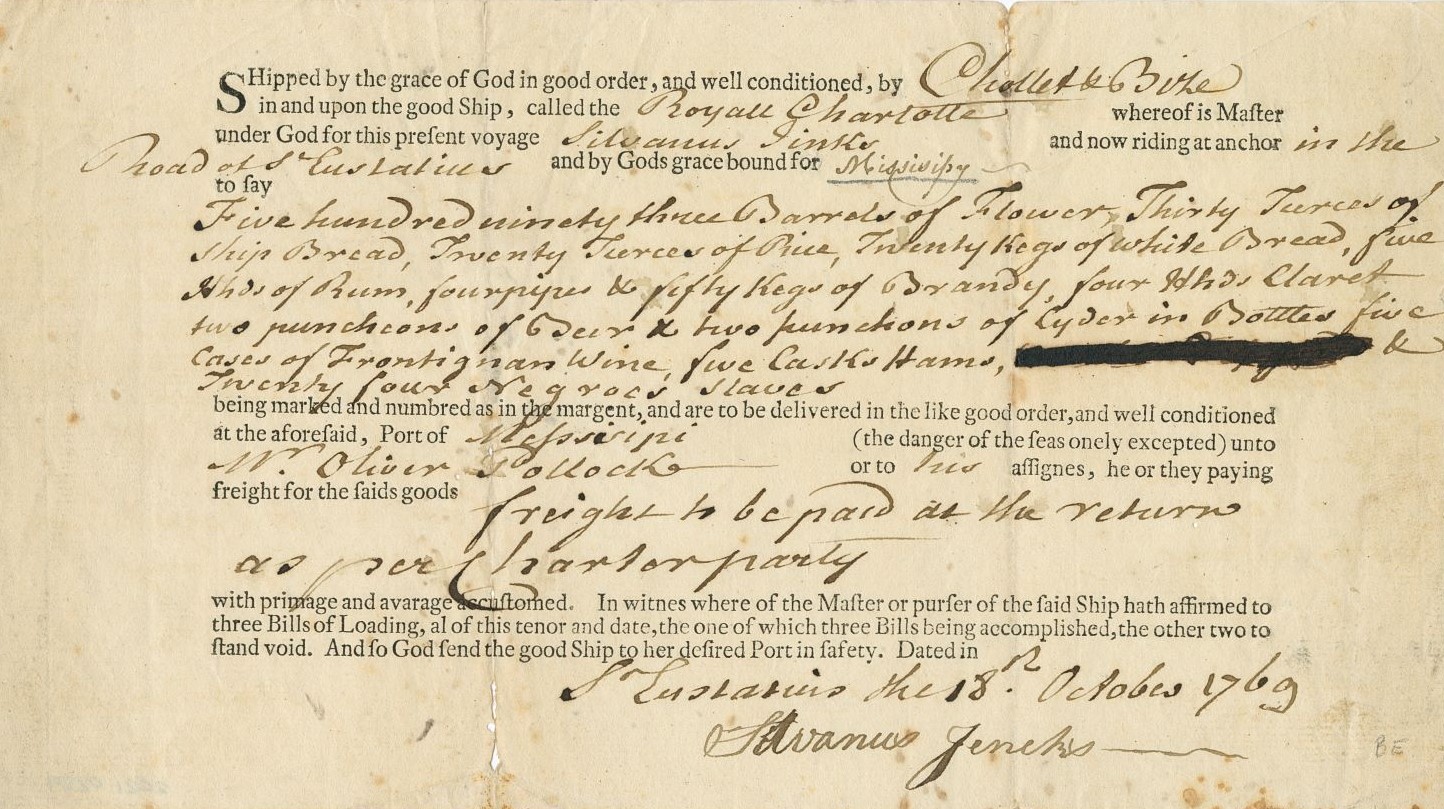

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Bill of lading for goods and slaves shipped aboard the Royal Charlotte to Oliver Pollock.

In spring 1778 Oliver Pollock was at the height of his career. The Irish-born merchant owned numerous properties across Spanish Louisiana and British West Florida. His successes linking New Orleans to markets in the Illinois Country, the Caribbean, and eastern North America also allowed him to play an active role in supporting the American Revolution on the side of the Patriots. Pollock’s efforts, however, which largely came in the form of financial backing, proved his downfall. When the new United States failed to repay its debts, Pollock himself was held accountable—and he spent the rest of his life seeking to recover his sunken social and professional standing.

Early Life

Oliver Pollock was born likely in 1737 in Coleraine, a town in what is now Northern Ireland. The Pollocks descended from Scottish Presbyterian settlers in the region, or the Ulster Scots, many of whom prospered as farmers and linen producers. Oliver’s father Jared, however, was not so successful. Struggling economically, Jared Pollock migrated with several family members—including Oliver—to western Pennsylvania in 1760, where they settled in the Scots Irish community of Carlisle.

Frontier life did not suit Oliver. Within a year, the Irishman relocated to Philadelphia, where he connected with Willing & Morris, one of the city’s major commercial firms. The company sent Pollock as a corresponding agent to Havana in 1762 to sell supplies to the British Army. He remained after Cuba returned to Spanish control in 1763 and used his British citizenship along with his unique permission to reside in Spanish territories to establish an otherwise illegal trade between two empires. Pollock also socialized with the island’s Irish community. In 1765 he married Margaret O’Brien, the daughter of a local merchant, with whom he would have eight children. It was in Cuba, too, that Pollock first met Alejandro O’Reilly, an Irish general sent by King Charles III to reassert Spanish control after the Seven Years’ War.

Becoming Established in Louisiana

In 1769 O’Reilly was sent to New Orleans to deal with the uprising against Governor Antonio de Ulloa. Pollock arrived shortly thereafter, bringing with him a shipload of flour that he sold in the grain-starved colony at face value, rather than a profit. The act earned him O’Reilly’s goodwill as well as the right to freely trade across Louisiana. Pollock seized this privilege. He continued to coordinate with Willing & Morris to import flour and manufactured goods from Philadelphia, but he also worked with companies like Baynton, Wharton & Morgan to ship animals pelts from the Illinois Country. The Irishman similarly invested in the transatlantic and circum-Caribbean slave trade, using his purchase and resale of Africans and African Americans to make quick profits and to fund his continued ventures.

Pollock pursued land grants in both Spanish Louisiana and British West Florida. He eventually acquired acreage at Chapitoulas, in the LaFourche district, along the Tangipahoa River, south of Baton Rouge, near Pointe Coupee, and at Tunica Bend, the last on which he built a profitable indigo plantation overseen by his cousin, Hamilton Pollock.

The American Revolution

By the 1770s, Oliver Pollock was a major regional presence, and when the rebelling British American colonies sought a representative to petition their cause to the Spanish governors, he was a natural choice. As early as September 1776, Pollock helped George Gibson, a Virginia military officer, negotiate shipments of gunpowder from Spain to the new United States. In spring 1778 Pollock again demonstrated his dedication to the Patriots by procuring for James Willing—a one-time business partner—safe haven in New Orleans after the latter raided British plantations in West Florida. The Irishman also obtained from Louisiana Governor Bernardo de Gálvez permission to sell the “spoils” of Willing’s initial expedition—eighty-five enslaved men and women. The auction raised so much money for the Americans that Pollock reoutfitted a captured British ship to specifically engage in slave raiding. The Continental Congress, followed by the state of Virginia, acknowledged his efforts by officially designating the Irishman their agent in Louisiana later that year.

Pollock’s fortunes, however, soon took a turn. In summer 1778, at the request of congressional leaders, he began to support the military efforts of George Rogers Clark in the Illinois Country. He did this by sending both bills of exchange, backed by his name, and supplies upriver. Clark and his associates, however, miscalculated the Irishman’s wealth and overdrew on his accounts. By 1779 Pollock was unable to pay his bills. Across the next three years, Pollock was forced to sell enslaved laborers and several plantations, borrow money in New Orleans at steep interest rates, and even obtain a loan from Governor Galvéz for $74,000. A bill from Clark’s Fort Jefferson in January 1782 for a significant $237,320 proved Pollock’s final straw. Facing demands for his debt imprisonment in New Orleans, the Irishman left Louisiana to petition for his repayment directly from Congress.

Later Life

Pollock chased these sums for the next thirty-five years. Unable to provide immediate reimbursement, the United States offered him the position of commercial agent to Cuba in 1783. Unfortunately, the Irishman’s debts from Spanish Louisiana followed him, and he was jailed in Havana for almost a year. Finally, in 1785, Pollock received his first repayment from Virginia, which he used to pay down his own accounts as well as to outfit a ship with goods to sell in New Orleans in 1788. Its arrival was timely. The city had just endured a devastating fire and was in dire need of materials to rebuild. Among those items the Irishman offered for sale was the city’s first pump fire engine, bought (belatedly) from Benjamin Franklin’s fire company in Philadelphia.

Pollock used the profits of these sales to rebuild his Louisiana estate, including repurchasing his Old Tunica Plantation in 1789. Nonetheless, in 1791, he returned to the United States and settled near Carlisle until a few years after his wife Margaret’s death in 1799. He remarried Winifred Deady in 1805, and the couple lived in Baltimore until her death in 1814. Pollock finally returned to the lower Mississippi River in 1819, where he resided with his daughter Mary Robinson near Pinckneyville, Mississippi, until his death in 1824. In the end, he was entirely reimbursed by the United States and Virginia for the support he offered each during the American Revolution, although this took until 1811 and 1819 respectively.