Opelousas Massacre of 1868

The deadliest episode of Reconstruction-era racial violence, the Opelousas Massacre of 1868 left more than two hundred Black people dead and established a near century-long precedent of Black voter suppression in St. Landry Parish.

Library of Congress

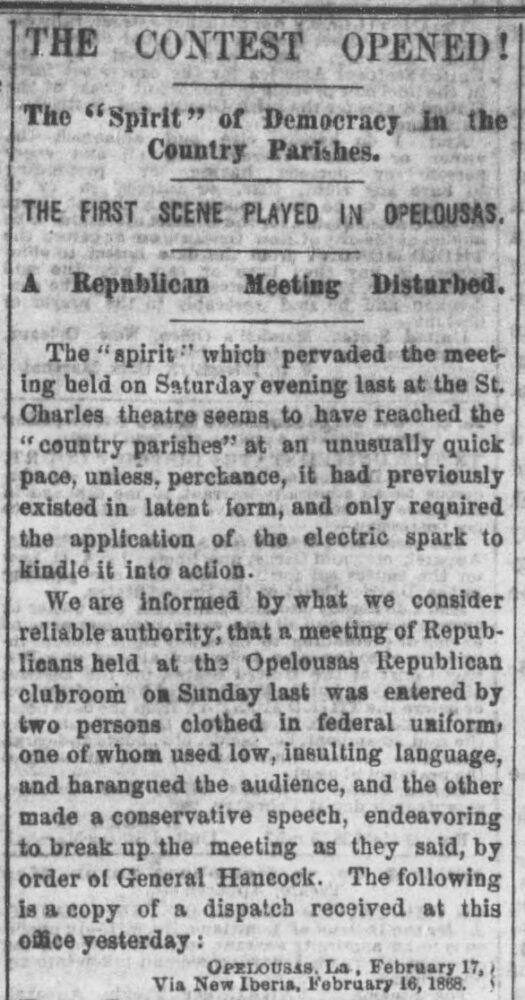

Coverage of a disturbance at a Republican meeting held in Opelousas shortly after the federal expansion of voting rights. New Orleans Republican, February 18, 1868.

In April 1868, a year after the First Reconstruction Act established Black male suffrage in Louisiana, the male population of St. Landry Parish narrowly split its vote, giving pro-Confederate Democrats wins at the local level while choosing Republicans to fill state offices. Slim margins of victory up and down the ballot underscored the new political landscape: Black men now played a significant role in determining election outcomes. With the November presidential contest between Republican Ulysses S. Grant and Democrat Horatio Seymour on the horizon, leaders in both parties jostled to recruit Black voters to gain control of the White House.

Democratic party bosses used a combination of enticement and intimidation to diversify their nearly all-white rolls, hosting barbecues by day and marching with torches at night. Republican leaders, in turn, held weekly meetings with impassioned community orators to solidify the parish’s large Black electorate. Local Black organizers found white allies in a handful of Radical Republicans that largely hailed from outside the region, including men like Ohio-born Emerson Bentley. Arriving in the parish seat of Opelousas that July, eighteen-year-old Bentley served as the sole instructor at the Freedmen’s Bureau school while also assisting with voter registration. He quickly earned the ire of the community’s white residents, some of whom tacked a drawing of a skull and bones alongside a coffin and bloody dagger to the schoolhouse door. The note read, “E. B. Beware! KKK.”

Hostilities between the two factions grew steadily that summer, fueled by an onslaught of incendiary rhetoric appearing on the pages of the Democratic Opelousas Courier and Radical Republican St. Landry Progress. After the latter announced a September 13 march to the nearby town of Washington to rally Black voters—a notice that advised participants to come armed—Democrats prepared for confrontation. On the day of the procession, white residents lined the streets to await the group’s arrival. A riot was narrowly averted after one of the marchers discharged their gun into the air, causing party leaders to call a truce.

Both sides agreed to open their meetings to the public and ban all attendees from carrying weapons or drinking alcohol. They also negotiated an end to the inflammatory rhetoric in speech or print. The same day the truce was decided, however, Bentley published a passionate account of the previous week’s incident in Washington, accusing his foes of harassment, intimidation, and other unscrupulous tactics. Believing the editorial violated the accord, three prominent Democrats visited Bentley at his school on the morning of September 28, demanding a retraction.

One of the men, a local attorney who later became district judge, physically accosted Bentley, striking him repeatedly with his cane as students watched in horror. Believing the blows to be lethal, the panicked children fled the schoolhouse and shouted that their teacher had been killed. Bentley survived, however, and, after detailing the attack in an affidavit to the parish’s justice of the peace, went into hiding. Ten days later he escaped on a steamboat to New Orleans.

As false rumors of Bentley’s violent death swept across St. Landry, indignant Black citizens gathered that afternoon in small armed bands on the outskirts of Opelousas, including two dozen who assembled at the plantation of a Black Creole man named Hilaire Paillet. While discussing the situation, a party of deputized white men on horseback approached and ordered them to disarm. The dissidents refused and gunfire erupted, leaving individuals in both factions wounded and one Black man dead. The police promptly took the surviving Black participants into custody and imprisoned them in the local jail.

By the next day, September 29, roughly two thousand armed, agitated white people had converged in town, and that night a lynch mob broke into the jail, murdering the twenty-seven Black people held there by firing squad. Over the next two weeks vigilantes killed approximately 250 Black individuals, along with several white radicals. Bodies were thrown into shallow graves, and one corpse was put outside an Opelousas drugstore to warn would-be Republican sympathizers. Hundreds of Black residents fled the parish while those who stayed and desired protection tied red ribbons around their arms to signal their compliance.

The reign of terror, including the ransacking of the Freedmen’s school and destruction of the St. Landry Progress’s printing press, effectively erased the Republican Party from St. Landry’s political landscape. Indeed, in the 1868 presidential election, no vote was cast for its candidate, former Union Army General Ulysses S. Grant. The supervisor for voter registration later observed, “I am fully convinced that no man on that day could have voted any other than the Democratic ticket and not been killed inside of twenty-four hours.”