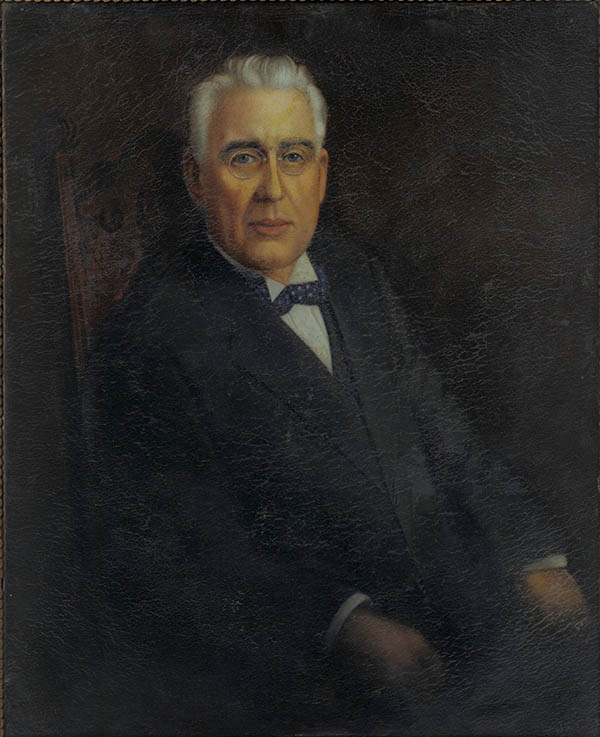

William Ratcliffe Irby

William Ratcliffe Irby, a wealthy tobacco company executive, banker, and philanthropist in New Orleans, became a driving force in saving the French Quarter from potential mass demolition.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

William Ratcliffe Irby. Billings, G. F. (artist)

William Ratcliffe Irby, a wealthy tobacco company executive, banker, and philanthropist in New Orleans, became a driving force in saving the French Quarter from potential mass demolition. His acquisition and restoration of many historic properties in the blocks that constituted the original city encouraged others investors to follow suit, resulting in the turnaround of a largely intact eighteenth- and nineteenth-century neighborhood that had devolved into an overcrowded slum by the turn of the twentieth century

Irby was born on January 4, 1860, in Lynchburg, Virginia, and his family moved to New Orleans in 1866. Irby followed the career path of his father, James Jackson Irby, and joined the tobacco business. He became one of the chief executives of American Tobacco Company—once the world’s largest tobacco supplier, a veritable business empire owned by the powerful Duke family of North Carolina—until an anti-trust Supreme Court ruling in 1911 divided the monopoly into multiple companies. Of the various companies that emerged from the federal lawsuit, there were four major players: Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, P. Lorillard Company, R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, and a reduced-in-size American Tobacco Company.

A February 15, 1912, New York Times article reported that of the original twenty-seven-member board of American Tobacco, seven resigned to go with P. Lorillard and Liggett & Myers. Four of the seven—C. C. Dula, R. B. Dula, R. D. Lewis, and William Ratcliffe Irby—became directors of Liggett & Myers. The Irby branch of American Tobacco in New Orleans had manufactured cigarettes and smoking tobacco; its main brands were “King Bee” and “Home Run.” The New Orleans factory became one of many Liggett & Myers operations, with a cigarette factory in St. Louis, Missouri, being the largest.

Besides serving as director of Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, Irby was also a successful banker, serving as chairman of the Canal Bank & Trust Company of New Orleans. Irby, also president of Tulane University’s board of administrators, was instrumental in setting up the university’s central purchasing system, and a dormitory on the campus was named for him.

On September 29, 1915, a Category-4 hurricane inflicted major damage to the New Orleans area, destroying or damaging several historic structures. Many of these landmarks were in the French Quarter. The exterior structure of the Presbytere’s cupola was demolished in that storm (and was not restored until 2005), and the abandoned St. Louis Hotel collapsed. The 1915 hurricane—as well as years of neglect—had left much of the French Quarter very much in a state of disrepair. Irby, who was described in Time magazine as “a representative old-school Southerner of great power and dignity,” began taking notice of this situation and decided to do something about it. St. Louis Cathedral had been another victim of the 1915 hurricane, suffering major foundation deterioration, among other problems. Irby gave a gift of $125,000 to help correct the storm’s damage—with the stipulation that his generosity remain anonymous. Irby’s gift to the Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans was not revealed until after his death.

The French Opera House, a performing arts venue built in 1859, was another landmark Irby rescued. By 1913 the grand old house had fallen on hard times and was forced into receivership. Once again, Irby’s anonymous donation allowed for the purchase and transfer of the building to Tulane University, along with the backing to operate it under the new leadership of the French tenor Agustarello Affré. The Opera House reopened, and its future looked promising, but the building was consumed by flames on the night of December 4, 1919.

Another familiar landmark Irby saved was the building located at 417 Royal Street between Conti and St. Louis Streets. It was built in 1795 by Vincent Rillieux (great-grandfather of the artist Edgar Degas), who purchased the site a month after the great fire of December 8, 1794. In 1805 it housed the Banque de la Louisiane, the first bank established after the Louisiana Purchase, and was later the family home of world chess champion Paul Morphy, who died there on July 10, 1884. Irby donated the building to Tulane University in 1920. Restaurateur Owen Brennan rented the property from Tulane in 1954, renovating and restoring the historic structure while establishing his innovative and hugely popular restaurant, Brennan’s. In 1984 Tulane sold the property to Brennan’s three sons, Pip, Jimmy, and Ted, but the venerable dining establishment closed in 2013 after prolonged internecine disputes and financial troubles.

In 1918 Irby purchased and restored the Brulatour residence at 520 Royal Street. Also known as the Seignoret House, it was erected in 1816 by Francois Seignoret, a fine furniture and wine merchant who was a native of Bourdeaux, France. Seignoret leased part of his ground-floor footage to Antoine Michoud, a merchant. Pierre Brulatour (also a wine importer) bought the house in 1870, the same year that Jules Brulatour, one of the cofounders of Universal Pictures, was born in New Orleans. Irby bought the house after three decades of neglect and set out to restore it for his own residence. The property at 520 Royal was purchased by The Historic New Orleans Collection in 2006, but from 1950 to 1966, it was home to the studios and offices of the New Orleans’s first local television affiliate, WDSU-TV.

In 1921 Irby bought the block-long building known as the Lower Pontalba Apartments for $68,000 from Michel Joseph Gaston Delfau de Pontalba, grandson of the Baroness Pontalba, who in the 1840s oversaw the construction of the famous red-brick apartment buildings flanking Jackson Square. In his will Irby bequeathed the historic apartment building to the Louisiana State Museum, and it maintains control today.

On Saturday morning, November 20, 1926, Irby went about his day in his normal manner. He visited the bank, performed a few routine duties, and had a mid-morning cup of coffee. He next took a cab to the Tharp-Sontheimer-Tharp undertaking parlors at Carondelet and Toledano Streets. The Times-Picayune reported that Irby “greeted the attendants affably” and told them he had “come to make arrangements for a funeral.” He looked at coffins on the second floor and then requested a morning newspaper. When the undertaker went downstairs to fetch the paper, Irby, sitting on a sofa, fired a revolver into his right temple. He left a note “requesting simplicity in his funeral.” A second note cited an “incurable heart disease” as the reason for his suicide. He was buried in New Orleans’s Metairie Cemetery.